Nature: Introduction; Struggle (Charles Darwin, Arthur Schopenhauer); Organicism (A.N. Whitehead)

Nature: Introduction; Struggle (Charles Darwin, Arthur Schopenhauer); Organicism (A.N. Whitehead)_____

Introducing the third section, "Nature," the editors try to make it clear what the authors surveyed are talking about:It is a principle of biological struggle, of battle for survival, yet it is also a principle of organic harmony, vital unison in things. It is automatic material energy, a complex of mechanical physical forces that menace human existence; but in still another perspective it may be seen as the very source and sanction of human inventiveness, or even as a construction of human intelligence, created by scientists in the course of physical experiment.

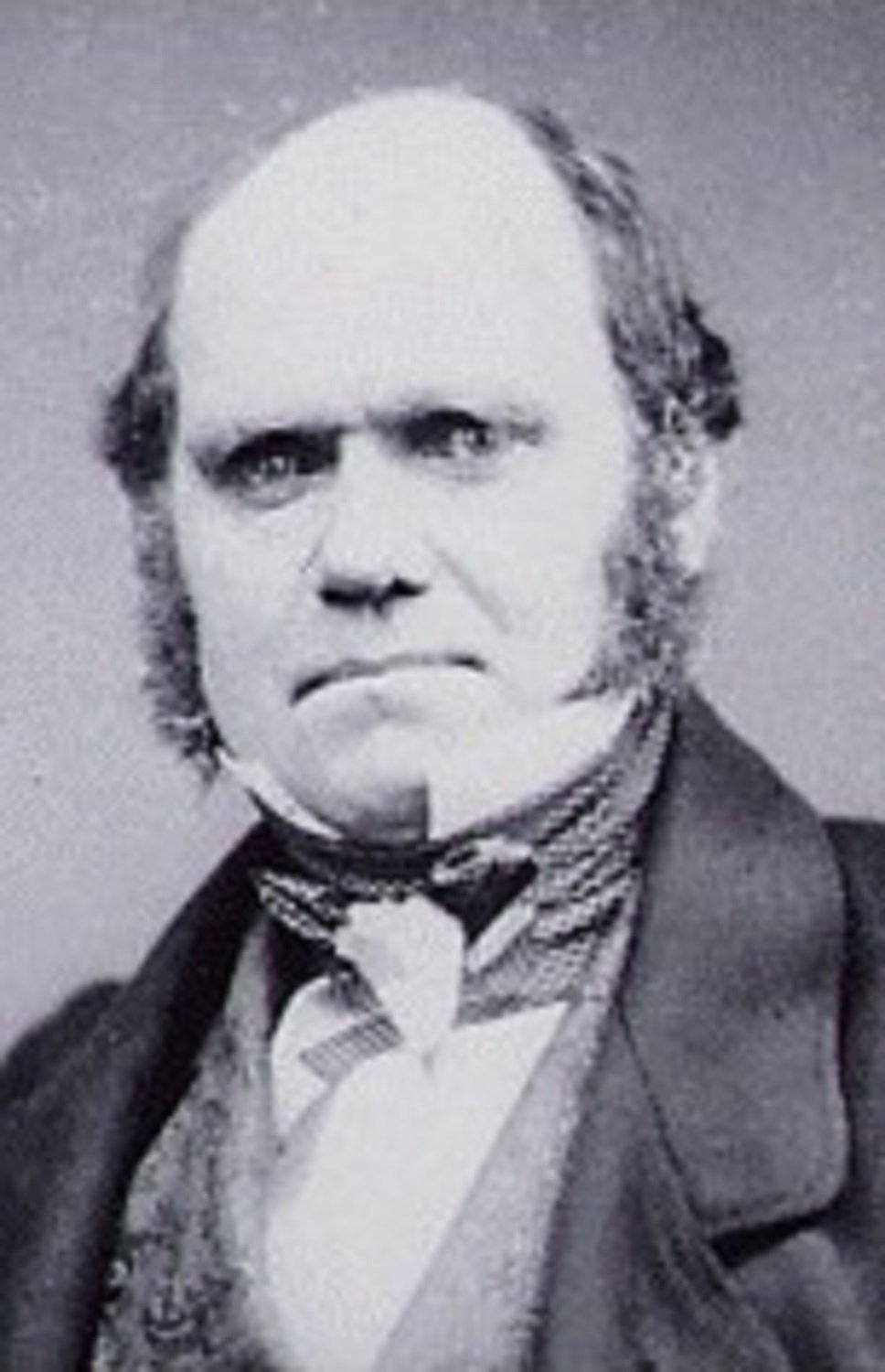

Charles Darwin: The Struggle for Existence and Natural Selection

|

| Charles Darwin in 1854 |

It's odd, considering that the central premise of Darwin's theory, that "the struggle of life" produces winners and losers and that the winners are those best adapted to the conditions in which they struggle, would seem to be perfectly harmonious with the tenets of the free-market conservatives who are most likely to protest against the theory.

Owing to this struggle, variations, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if they be in any degree profitable to the individuals of a species, in their infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to their physical conditions of life, will tend to the preservation of such individuals and to their offspring."Natural Selection" was Darwin's term for the process, but he approved of Herbert Spencer's "Survival of the Fittest" as "more accurate, and ... sometimes equally convenient." He observed that the process was already known to breeders of animals, but that its course in the wild was "immeasurably superior to man's feeble efforts, as the works of Nature are to those of Art." (Thereby setting off the Nature vs. Art debate once again, to rage through the rest of the century and into the next.) The one thing Darwin was most concerned to eliminate was sentimentality about Nature. "We behold the face of nature bright with gladness, we often see superabundance of food; we do not see or we forget, that the birds which are idly singing round us mostly live on insects or seeds, and are thus constantly destroying life."

"Natural selection," he admits, can be a misleading term. For one thing, it seems to some to imply a "selector," which is not at all what Darwin has in mind: "it is difficult to avoid personifying the word Nature; but I mean by Nature, only the aggregate action and product of many natural laws, and by laws the sequence of events as ascertained by us. It also has promoted the notion of "lower" and "higher" forms of life, which is not at all what is involved: The only criterion implied by the term is success at living in a given environment, and success at reproducing. "No country can be named in which all the native inhabitant are now so perfectly adapted to each other and to the physical conditions under which they live, that none of them could still be better adapted or improved." Any given variation within a species can be judged only by its usefulness toward surviving.

And human interference only complicates things: "Man selects for his own good: Nature only for that of the being which she tends." (Darwin has just once again apologized for personifying Nature, explaining that what he means is really "the natural preservation or survival of the fittest.")

Under nature, the slightest differences of structure or condition may well turn the nicely-balanced scale in the struggle for life, and so be preserved. How fleeting are the wishes and efforts of man! how short his time! and consequently how poor will be his results, compared with those accumulated by Nature during whole geological periods! Can we wonder, then, that Nature's productions should be far "truer" in character than man's productions; that they should be infinitely better adapted to the most complex conditions of life, and should plainly bear the stamp of far higher workmanship.That last phrase, "the stamp of far higher workmanship," has a theistic whiff to it, suggesting Darwin's discomfort with the non-theistic implications of his theory. But he goes boldly onward to proclaim his "belief that all animals and plants are descended from some one prototype," and moreover "that all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth may be descended from some one primordial form." Still, he clings to the myth of a Creator:

To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those determining the birth and death of the individual. When I view all beings not as special creations, but as the lineal descendants of some few beings which lived long before the first bed of the Cambrian system was deposited, they seem to me to become ennobled.There is no escaping the sense that Darwin was struggling to align his theory with the orthodox religious view as much as possible, doing a kind of cheerleading for the theory as a positive, almost holy, view of nature, without outright proclaiming it as "God's plan": "as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection." The question remains: perfect by whose standards? But in the famous "tangled bank" paragraph, he reaches toward an optimistic view of the struggle for existence and a reconciliation with the orthodox account of creation:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.

Arthur Schopenhauer: The Will in Nature

|

| Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl, Portrait of Arthur Schopenhauer, c. 1815 |

When we experience pain, Schopenhauer asserts, we are experiencing that which "is opposed to the will; gratification and pleasure when it is in accordance with it." Pain and pleasure are "immediate affections of the will, in its manifestation, the body." By will, Schopenhauer doesn't just mean individual determination, as in "I will be heard!" or "His will is law." Will is a fundamental force in nature. It includes

- "the force which germinates and vegetates in the plant"

- "the force through which the crystal is formed"

- "that by which the magnet turns to the north pole"

- "the force whose shock [one] experiences from the contact of two different kinds of metals"

- "the force which appears in the elective affinities of matter as repulsion and attraction, decomposition and combination"

- "and, lastly, even gravitation, which acts so powerfully throughout matter, draws the stone to the earth and the earth to the sun"

All of these forces and others are the same thing: will. We experience them as separate phenomena, as ideas. "Phenomenal existence is idea and nothing more ... but the will alone is a thing in itself." Will "appears in every blind force of nature and also in the preconsidered action of man; and the great difference between these two is merely in the degree of the manifestation, not in the nature of what manifests itself." Such characteristics of matter "as rigidity, fluidity, elasticity, electricity, magnetism, chemical properties and qualities of every kind ... are in themselves immediate manifestations of will."

In the higher grades of the objectivity of will we see individuality occupy a prominent position, especially in the case of man, where it appears as the great difference of individual characters, i.e., as complete personality, outwardly expressed in strongly marked individual physiognomy, which influences the whole bodily form.... The farther down we go, the more completely is every trace of the individual character lost in the common character of the species, and the physiognomy of the species alone remains.Will also manifests itself in the struggle of existence, in "the burden of physical life, the necessity of sleep, and finally, of death; for at last these subdued forces of nature, assisted by circumstances, win back from the organism, wearied even by the constant victory, the matter it took from them.... Thus everywhere in nature we see strife, conflict, and alternation of victory ... indeed nature exists only through it." As Darwin would be later, Schopenhauer is impressed by the fact that "each animal can only maintain its existence by the constant destruction of some other. Thus the will to live everywhere preys upon itself, and in different forms is its own nourishment." But Schopenhauer extends this process of struggle even to inanimate matter, "when, for example, crystals in process of formation meet, cross, and mutually disturb each other to such an extent that they are unable to assume the pure crystalline form, so that almost every cluster of crystals is an image of such a conflict of will at this low grade of its objectification." And just as in the microcosm, so in the macrocosm: "the constant tension between centripetal and centrifugal force ... keeps the globe in motion."

So if you're searching for an ultimate, you've found it: "Will is the thing-in-itself, the inner content, the essence of the world. Life, the visible world, the phenomenon, is only the mirror of the will."

Birth and death belong merely to the phenomenon of will, thus to life; and it is essential to this to exhibit itself in individuals which come into being and pass away, as fleeting phenomena appearing in the form of time -- phenomena of that which in itself knows no time, but must exhibit itself precisely in the way we have said, in order to objectify its peculiar nature.A student of Hinduism, Schopenhauer notes that Shiva (or Siva, as he spells it), the god associated with destruction and death is given "as an attribute not only the necklace of skulls, but also the lingam, the symbol of generation, which appears here as the counterpart of death, thus signifying that generation and death are essentially correlatives, which reciprocally neutralise and annul each other."

Again like Darwin, Schopenhauer asserts that "it is not the individual, but only the species that Nature cares for, and for the preservation of which she so earnestly strives, providing for it with the utmost prodigality through the vast surplus of the seed and the great strength of the fructifying impulse.... [Nature's] kingdom is infinite time and infinite space.... Therefore she is always ready to let the individual fall." Nature assures continuation by making sex pleasurable. "On the other hand, excretion, the constant exhalation and throwing off of matter, is the same as that which, at a higher power, death, is the contrary of generation." In this scheme of things, in which the physical being is merely an instrument of generation, "It appears just as foolish to embalm the body as it would be to carefully preserve its excrement."

Man alone carries about with him, in abstract conceptions, the certainty of his death; yet this can only trouble him very rarely, when for a single moment some occasion calls it up to his imagination. Against the mighty voice of Nature reflection can do little. In man, as in the brute with does not think, the certainty that springs from his inmost consciousness that he himself is Nature, the world, predominates as a lasting frame of mind; and on account of this no man is observably disturbed by the thought of certain and never-distant death, but lives as if he would live forever.

A.N. Whitehead: Nature as Organism

|

| A.N. Whitehead, date unknown |

Whitehead is preoccupied with organisms in relation to their environment, and at the same time he is seeking to interpret the world of physics, the science of inorganic energy.... He regards the official philosophy of early twentieth-century science, which he traces back to the seventeenth century, as misleading because of its mechanistic assumptions: it makes objects falsely self-sufficient and isolates them from the minds that apprehend them. Whitehead would establish instead a recognition that he finds first expressed in the romantic poets: we do not perceive particular elements in nature as discrete entities, to the exclusion of other elements or to the exclusion of ourselves. Things and the perception of things are events, modes of interaction with other events in space and time. Parts of nature assume individuality by drawing the surrounding world into themselves and delimiting it; but these individual unities must also be seen in terms of larger unities of which they are functions. As in a plant, the whole dominates each part, and as in organic growth every partial whole virtually contains the whole that transcends it.The excerpts come from Science and the Modern World, based on the Lowell Lectures Whitehead gave at Harvard in 1925. He begins with the usual definitions of terms, explaining that "matter, or material, is anything which has this property of simple location.... one major characteristic which refers equally both to space and to time, and other minor characteristics which are diverse as between space and time." Got that? Good. "The characteristic common both to space and time is that material can be said to be here in space and here in time, or here in space-time." The seventeenth century scientists asserted "that the world is a succession of instantaneous configurations of matter." This was a perfectly useful definition for them. It "is the famous mechanistic theory of nature, which has reigned supreme ever since the seventeenth century. It is the orthodox creed of physical science. Furthermore, the creed justified itself by the pragmatic test. It worked." But there are some problems with it, and Whitehead has a famous phrase for it: "the Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness," by which he means "the accidental error of mistaking the abstract for the concrete."

In addition to "simple location," Whitehead says "substance and quality ... are the most natural ideas for the human mind. It is the way we think of things, and without these ways of thinking we could not get our ideas straight for daily use." But, he asks, "How concretely are we thinking when we consider nature under these conceptions?" Suppose, he says, we observe of an object that "it is hard, and blue, and round, and noisy." But are these qualities of the object itself, or are they what we bring to them by perceiving them?

These sensations are projected by the mind so as to clothe appropriate bodies in external nature. Thus the bodies are perceived as with qualities which in reality do not belong to them, qualities which in fact are purely the offspring of the mind. Thus nature gets credit which should in truth be reserved for ourselves; the rose for its scent: the nightingale for his song: and the sun for his radiance. The poets are entirely mistaken. They should address their lyrics to themselves, and should turn them into odes of self-congratulation on the excellency of the human mind. Nature is a dull affair, soundless, scentless, colourless; merely the hurrying of material, endlessly, meaninglessly.Yet since the seventeenth century, science has dealt with nature this way. "The enormous success of the scientific abstractions, yielding on the one hand matter with its simple location in space and time, on the other hand mind, perceiving, suffering, reasoning, but not interfering, has foisted onto philosophy the task of accepting them as the most concrete rendering of fact.... It involves a fundamental duality, with material on the one hand, and on the other hand mind."

Whitehead proposes that we analyze things in space and time: "Things are separated by space, and are separated by time: but they are also together in space, and together in time, even if they be not contemporaneous." So space-time is characterized by the separative and the prehensive, and also because everything in space has a definite location (it can't be in two places at once) and because "it endures during a certain period and through no other period" in time, it also has a modal character. It's the modal character that suggests the idea of simple location. "But it must be conjoined with the separative and prehensive characters."

The volume is the most concrete element of space. But the separative character of space, analyses a volume into sub-volumes, and so on indefinitely.... But it is the unity of volume which is the ultimate fact of experience.... Accordingly, the prime fact is the prehensive unity of volume, and this unity is mitigated or limited by the separated unities of the innumerable contained parts.... The parts form an ordered aggregate, in the sense that each part is something from the standpoint of every other part, and also from the same standpoint every other part is something in relation to it."Prehension" is a grasping of unity, and "Perception is simply the cognition of prehensive unification; or more shortly, perception is cognition of prehension. The actual world is a manifold of prehensions; and a "prehension" is a "prehensive occasion"; and a prehensive occasion is the most concrete finite entity, conceived as what it is in itself and for itself.... Nature is conceived as a complex of prehensive unifications."

Nature is, then, a process, a series of events. "Simple location" is no longer relevant. And "space-time is nothing else than a system of pulling together of assemblages into unities." An event has a past, present and future. "These conclusions are essential for any form of realism. For there is in the world for our cognisance, memory of the past, immediacy of realisation, and indication of things to come."

What we're dealing with now are organisms, "so that the plan of the whole influences the very characters of the various subordinate organisms which enter into it.... Thus an electron within a living body is different from an electron outside it, by reason of the plan of the body ... and this plan includes the mental state."

Whitehead now turns, thankfully, to literature, where he finds "the most interesting criticism of the thoughts of science among the leaders of the romantic reaction which accompanied and succeeded the epoch of the French Revolution." Chief among them, for Whitehead's purposes, are Wordsworth and Shelley. (Keats he dismisses, rather oddly, as "an example of literature untouched by science," and Coleridge as "only important by his influence on Wordsworth." Byron and Blake apparently are beyond consideration.) Wordsworth, he says, "alleges against science its absorption in abstractions. His consistent theme is that the important facts of nature elude the scientific method." Wordsworth "always grasps the whole of nature as involved in the tonality of the particular instance.... the first book of The Prelude ... is pervaded by this sense of the haunting presences of nature.... Wordsworth, to the height of genius, expresses the concrete facts of our apprehension, facts which are distorted in the scientific analysis."

Unlike Wordsworth, Shelley loved science, which "symbolises to him joy, and peace, and illumination.... What the hills were to Wordsworth, a chemical laboratory was to Shelley.... If Shelley had been born a hundred years later, the twentieth century would have seen a Newton among chemists." Shelley perceives the organic character of nature, "functioning with the full content of our perceptual experience." In his poems you see "an emphatic witness to a prehensive unification as constituting the very being of nature. Berkeley, Wordsworth, Shelley are representative of the intuitive refusal seriously to accept the abstract materialism of science."

In "The Cloud," Shelley examines "the endless, eternal, elusive change of things.... Every scheme for the analysis of nature has to face these two facts: change and endurance. There is yet a third fact to be placed by it, eternality, I will call it."

The mountain endures. But when after ages it has been worn away, it has gone. If a replica arises, it is yet a new mountain. A colour is eternal. It haunts time like a spirit. It comes and it goes. But where it comes, it is the same colour. It neither survives nor does it live. It appears when it is wanted. The mountain has to time and space a different relation from that which colour has.The nineteenth century English poets performed a valuable service in pointing out "the discord between the aesthetic intuitions of mankind and the mechanism of science." They make us aware that "a philosophy of nature must concern itself at least with these six notions: change, value, eternal objects, endurance, organism, interfusion."

You are in a certain place perceiving things. Your perception takes place where you are, and is entirely dependent on how your body is functioning. But this functioning of the body in one place, exhibits for your cognisance and aspect of the distant environment, fading away into the general knowledge that there are things beyond. If this cognisance conveys knowledge of a transcendent world, it must be because the event which is the bodily life unifies in itself aspects of the universe.... "Value" is the word I use for the intrinsic reality of an event. Value is an element which permeates through and through the poetic view of nature.

No comments:

Post a Comment