I don't know whether it's age or medication, but I no longer feel the obsessive-compulsiveness needed to keep up this blog. So I'm going back to my older, more casual blog, Bookishness, for whatever occasional observations on literature and life I may feel compelled to make. (If any.)

Grane, mein Ross....

javascript:void(0);

Ten Pages (or More)

JOURNAL OF A COMPULSIVE READER

By Charles Matthews

By Charles Matthews

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Friday, February 24, 2012

8. Genesis: The Bible. Commentary

From The Literary Guide to the Bible, edited by Robert Alter and Frank Kermode:

Introduction to the Old Testament, by Robert Alter

The Hebrew Bible that we know is an anthology. "One might imagine that religious ideology would provide the principle of selection for the anthology," and to the extent that no polytheistic or pagan texts are included, this is true.

In a conventionally didactic narrative, for example, Jacob and Esau would become simple antagonists, given that Jacob becomes Israel, "the covenanted people," and Esau becomes Edom, "one of its notorious historical adversaries."

Genesis, by J.P. Fokkelman

Genesis can be difficult to follow because it keeps switching "from the narrative flow to a more elevated style, that is, to the compactness of formal verse." It also constantly mixes genres:

"We meet with a colorful variety of action-directed narratives in the strictest sense, genealogical registers, catalogues, blessings and curses, protocols for the conclusion of covenants, doxological and mythological texts, etiological tales, legal directives."

It also mixes long units with short ones, and narrative reports with character speeches. "Some of the profoundest and most exciting stories are remarkably short but are found close to a long text which moves at a very relaxed pace." The intense drama of the command to Abraham to sacrifice his long-awaited son Issac takes up only about seventy lines. But this story is followed by "the calm flow, the epic breadth, and the poised harmony of characters, report, and speech in chapter 24, in which Abraham's servant seeks a bride for Isaac in Mesopotamia."

Sometimes the narrative flow is interrupted by other stories that don't seem directly relevant, as when the narrative about Jacob is broken by the story of the rape of Dinah and her brothers' revenge, or when the Joseph story is interrupted by the account of Judah and his daughter-in-law Tamar. But "we can integrate these passages thematically with their context despite their superficially digressive character."

And finally, the editor seems to have insufficiently blended discrete sources, as when the story of creation, in which humankind is presented as "created in God's image" and hence "as the crown of creation," is followed by a second account in which man is portrayed as "a morally shaky being who eagerly sloughs off responsibility and whose aspirations to become God's equal in knowledge of right and wrong are realized at the price of his own fall." Added to this is the inconsistency in which the creator is called "God" in the first version, but "Lord God" in the second. "And there seems to be a contradiction between 1:27 and 2:18-23 on the origin of nature and the relation between man and woman."

The Hebrew word toledot, which literally means "begettings," initiates these human genealogies. But it is also used in Genesis 2:4: "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth," as a conclusion to the first creation story.

The narrative also introduces recurrent threats to continuity, including the infertility of the three matriarchs, Sarah, Rebekah, and Rachel. And while primogeniture is considered of utmost importance in these societies, it is repeatedly "subverted or handled ironically." Ishmael is Abraham's firstborn, and Esau is Isaac's, yet neither becomes the heir, "and at the end old Jacob's blessing of Joseph's sons, Ephraim and Manasse, deliberately reverses younger and elder." The competition between older and younger children continues when "Laban exchanges Leah and Rachel behind the bridal veil at Jacob's marriage," ironically echoing Jacob's own deception of Isaac to gain his blessing: "the deceiver deceived."

The interpolated verses in Genesis serve "as crystallization points, they create moments of reflection."

Repetition is "an even more powerful structural instrument than poetry." Parallelisms run throughout Genesis, such as the antagonism between the brothers Jacob and Esau, which is repeated in the antagonism between Joseph and his brothers.

Introduction to the Old Testament, by Robert Alter

The Hebrew Bible that we know is an anthology. "One might imagine that religious ideology would provide the principle of selection for the anthology," and to the extent that no polytheistic or pagan texts are included, this is true.

But even within the limits of monotheistic ideology, there is a great deal of diversity in regard to political attitudes; conceptions of history, ethics, psychology, causation; views of the roles of law and cult, of priesthood and laity, Israel and the nations, even of God.... [So that] one begins to suspect that the selection was at least sometimes impelled by a desire to preserve the best of ancient Hebrew literature rather than to gather the consistent normative statements of a monotheistic party line.....

It is probably more than a coincidence that the very pinnacle of ancient Hebrew poetry was reached in Job, the biblical text that is most daring and innovative in its imagination of God, man, and creation; for here as elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible the literary medium is not merely a means of "conveying" doctrinal positions but an adventurous occasion for deepening doctrine through the play of literary resources, or perhaps even, at least here, for leaping beyond doctrine.The Hebrew Bible does contain a lot of stuff that we don't usually think of as "literature," such as "genealogies, etiological tales, laws (including the most technical cultic regulations, lists of tribal borders, detailed historical itineraries)." But Alter proposes that we see these "extra-literary" components as tools for reinforcing the themes of the narrative and poetic elements. "Thus J.P. Fokkelman proposes that the abundant genealogies in Genesis are enactments of the theme of propagation and survival so central to that book."

In any case, the Hebrew Bible, though it includes some of the most extraordinary narratives and poems in the Western literary tradition, reminds us that literature is not entirely limited to story and poem, that the coldest catalogue and the driest etiology may be an effective subsidiary instrument of literary expression.Alter sees the ancient Hebrew writers as masters of "an art of indirection," of a "narrative minimalism [that] was reinforced by their sense that stories should be told in a way that would move efficiently to the heart of the matter, never pausing to elaborate mimetic effects for their own sake." They were also alert to ambiguities in the stories they told: "ancient Hebrew narrative is ideological but not didactic."

In a conventionally didactic narrative, for example, Jacob and Esau would become simple antagonists, given that Jacob becomes Israel, "the covenanted people," and Esau becomes Edom, "one of its notorious historical adversaries."

But the story itself points toward a rather complicated balance of moral claims in the rivalry, perhaps because the writer, in fleshing out the individual characters, began to pull them free from the frame of reference of political allegory, and perhaps also because this is a kind of ideological literature that incorporates a reflex of ideological auto-critique.Of course, as Alter acknowledges, the stories in Genesis aren't the work of a single hand, but a "stitching together" of documents by various hands, the principal ones having been designated E, J, and P (and sometimes D) by German scholars in the nineteenth century. But whoever did the "stitching," Alter says, was so skilled "that often the dividing line between redactor and author is hard to draw, or if it is drawn, does not necessarily demarcate an essential difference." In Alter's view, "the redactors exhibited a genius in creating brilliant collages out of traditional materials," and he suspects that they often didn't "hesitate to change a word, a phrase, perhaps even a whole speech or narrator's report" to achieve the consistency of theme or structure they had in mind.

Genesis, by J.P. Fokkelman

Genesis can be difficult to follow because it keeps switching "from the narrative flow to a more elevated style, that is, to the compactness of formal verse." It also constantly mixes genres:

"We meet with a colorful variety of action-directed narratives in the strictest sense, genealogical registers, catalogues, blessings and curses, protocols for the conclusion of covenants, doxological and mythological texts, etiological tales, legal directives."

It also mixes long units with short ones, and narrative reports with character speeches. "Some of the profoundest and most exciting stories are remarkably short but are found close to a long text which moves at a very relaxed pace." The intense drama of the command to Abraham to sacrifice his long-awaited son Issac takes up only about seventy lines. But this story is followed by "the calm flow, the epic breadth, and the poised harmony of characters, report, and speech in chapter 24, in which Abraham's servant seeks a bride for Isaac in Mesopotamia."

Sometimes the narrative flow is interrupted by other stories that don't seem directly relevant, as when the narrative about Jacob is broken by the story of the rape of Dinah and her brothers' revenge, or when the Joseph story is interrupted by the account of Judah and his daughter-in-law Tamar. But "we can integrate these passages thematically with their context despite their superficially digressive character."

And finally, the editor seems to have insufficiently blended discrete sources, as when the story of creation, in which humankind is presented as "created in God's image" and hence "as the crown of creation," is followed by a second account in which man is portrayed as "a morally shaky being who eagerly sloughs off responsibility and whose aspirations to become God's equal in knowledge of right and wrong are realized at the price of his own fall." Added to this is the inconsistency in which the creator is called "God" in the first version, but "Lord God" in the second. "And there seems to be a contradiction between 1:27 and 2:18-23 on the origin of nature and the relation between man and woman."

Genesis is part of a grand design which unites the books of the Torah with Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings in one configuration: from the creation of the world through the choosing of the people of Israel and their settlement in Canaan up to the Babylonian Captivity. Genesis contributes two building blocks to this overarching plot: the Primeval History (1-11) and the protohistory of the people of Israel, namely the period of the eponymous forefathers (in three cycles: 12-25, 25-35, and 37-50).The genealogies provide a framework for this design: "Thus the lives of the protagonists Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph are presented within the framework of the begettings of their fathers (Terah, Isaac, and Jacob, respectively). This image of concatenation reveals the overriding concern of the entire book: life-survival-offspring-fertility-continuity."

The Hebrew word toledot, which literally means "begettings," initiates these human genealogies. But it is also used in Genesis 2:4: "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth," as a conclusion to the first creation story.

The word toledot is, then, a metaphor which, approaching the boundaries of the taboo in Israel's strict sexual morals, carries the oblique suggestion that the cosmos may have originated in a sexual act of God. It becomes evident how daring a game the writer is playing when we consider the world from which Israelite belief wished to dissociate itself: a world characterized by natural religion, fertility rites, cyclical thinking, and sacred prostitution; a world in which the idea of creation as the product of divine intercourse was a commonplace.Fertility and sexuality continue to be a crucial concern throughout Genesis. The shocked awareness of the first couple of their own nakedness is echoed in the story of Ham's sighting of the naked Noah, "in which the genitals of the father become taboo for the sons. Throughout Genesis, there is a debate over "what is or is not sexually permissible under special circumstances."

Tamar, who tricks her father-in-law into lying with her, is dramatically vindicated at the end of chapter 38; and it is by no means certain that the narrator condemns the curious case of incest in chapter 19 (where Lot's daughters ply their father with drink and become pregnant by him), even if he pokes fun at the dubious origin of the neighboring tribes Moab and Ammon.Sexuality is sanctioned by the command "Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth," and by the repeated promises to the patriarchs that their "seed" will thrive. But fertility is not enough: "offspring are not safe without a fixed habitat." So there is always a tension between the command to procreate and the promise of land for offspring. Time, too, exists as a threat: Abraham wants the heir he is promised in Chapter 12, when he is seventy-five. But he waits another twenty-five years before Isaac is born, and then God threatens to take Isaac away from him by demanding that Abraham sacrifice him. "Thus continuity is also threatened with destruction, and time itself with deprivation of purpose.... Genesis, in its thematic centering of time and space, constitutes the immovable foundation of the Torah and of the entire Hebrew Bible."

The narrative also introduces recurrent threats to continuity, including the infertility of the three matriarchs, Sarah, Rebekah, and Rachel. And while primogeniture is considered of utmost importance in these societies, it is repeatedly "subverted or handled ironically." Ishmael is Abraham's firstborn, and Esau is Isaac's, yet neither becomes the heir, "and at the end old Jacob's blessing of Joseph's sons, Ephraim and Manasse, deliberately reverses younger and elder." The competition between older and younger children continues when "Laban exchanges Leah and Rachel behind the bridal veil at Jacob's marriage," ironically echoing Jacob's own deception of Isaac to gain his blessing: "the deceiver deceived."

The interpolated verses in Genesis serve "as crystallization points, they create moments of reflection."

The parallelism of 1:27 ("So God created in in his own image, / in the image of God created he him, / male and female created he them") suggests that humankind is only in its twofoldness the image of God, which in its turn incorporates the fundamental equality of man and woman.(But then the second account of creation goes on to undermine this equality, by making woman a subordinate creation out of man.)

Repetition is "an even more powerful structural instrument than poetry." Parallelisms run throughout Genesis, such as the antagonism between the brothers Jacob and Esau, which is repeated in the antagonism between Joseph and his brothers.

Friday, February 17, 2012

7. Genesis: The Bible, pp. 75-82

Chapter 46

God appears to Jacob "in the visions of the night," and tells him not to be afraid to go to Egypt to see Joseph. So Jacob gathers all the family, sons and grandchildren, and "all the souls of the house of Jacob, which came into Egypt, were threescore and ten." Joseph goes out to meet them in the land of Goshen, and hugs his father and weeps "on his neck a good while."

Joseph says he is going to tell Pharaoh that they have arrived, that that they are shepherds who have brought all their animals with them. When he meets them, Pharaoh will asks what they do, and they should tell him they are shepherds, so they can live in the land of Goshen, "for every shepherd is an abomination unto the Egyptians." (Apparently this is something like the enmity between the farmers and the ranchers in the old West.)

Chapter 47

So Joseph takes five of his brothers and goes to Pharaoh, whom they ask to be allowed to live in the land of Goshen because of the famine in Canaan. Pharaoh agrees to the request. Then Joseph presents Jacob to Pharaoh, who asks how old Jacob is. He replies that he is one hundred thirty, but he hasn't reached the age that his fathers did. Jacob gives Pharaoh his blessing. So Joseph takes his brothers out to "the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.

The famine continues, and Joseph gathers all the money in Egypt and Canaan and buys grain with it. When the money is gone, Joseph tells them that he will accept their cattle in payment for grain. With the money and the cattle gone, people say that they have nothing left but their land and their bodies, so Joseph accepts the land as payment for grain, "so the land became Pharaoh's," except for the land held by the priests. Then Joseph gives them seed to plant, with the agreement that every fifth part belongs to Pharaoh.

Jacob lives in the land of Goshen, in Egypt, for seventeen years. When he is one hundred forty-seven, he has Joseph put his hand under his thigh and swear not to bury him in Egypt but to take him back and entomb him with his ancestors.

Chapter 48

When he is about to die, Jacob asks Joseph to bring his two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, for his blessing. Jacob's eyesight is failing, so he can't see the boys, but he tells Joseph that he had thought he would never see Joseph's face now, but "God hath shewed me also thy seed."

When Jacob puts his right hand on the head of Ephraim, the younger, and his left hand on Manasseh's head, Joseph protests that Manasseh is the firstborn. Jacob replies, "I know it, my son, I know it: he also shall become a people, and he also shall be great: but truly his younger brother shall be greater than he, and his see shall become a multitude of nations."

Chapter 49

Then Jacob calls all of his sons together to prophesy what will happen to each of them. Reuben, he says, is "Unstable as water," and will "not excel; because thou wentest up to thy father's bed; then defiledst thou it." (Reuben had slept with his father's concubine.) Simeon and Levi have "instruments of cruelty ... in their habitations." (They were responsible for the massacre in retaliation for the rape of Dinah.) He curses their anger and says "I will divide them in Jacob and scatter them in Israel."

Judah, on the other hand, "is a lion's whelp," who will dominate his enemies and be a ruler and lawgiver. Zebulon will live by the sea and deal with ships. "Issachar is a strong ass crouching down between two burdens." Dan will be a judge of his people. Gad will be overcome, but will himself overcome in the end. Asher's "bread shall be fat, and he shall yield royal dainties." Naphtali "giveth goodly words." Joseph has overcome what was done to him with the help of God, and will continue to prevail. As for Benjamin, he'll be like a wolf, devouring the prey in the morning and sharing it out at night. Naturally, all of these prophecies have been the subjects of extensive comment and exegesis, considering that they refer to the courses taken by the twelve tribes of Israel.

After reiterating his command (not just a wish) to be buried where Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, and Leah are buried, Jacob gives up the ghost. Joseph has him embalmed, and he is mourned for seventy days before Joseph gets Pharaoh's permission to take the body to the land of Canaan. Everyone, including the cattle, Pharaoh's servants and elders, chariots and horsemen, goes too: "it was a very great company."

After the funeral, Joseph and his brothers return to Egypt, though the brothers worry that, now that their father is dead, Joseph will decide to get even with them for casting him in the pit and selling him into slavery after all. But Joseph tells them not to worry: He isn't God, and it all turned out well in the end. He'll take care of them, he promises.

Joseph lives to be a hundred and ten, and gets to see his great-grandchildren in Ephraim's line and his grandchildren in Manasseh's. He was embalmed, and entombed in Egypt.

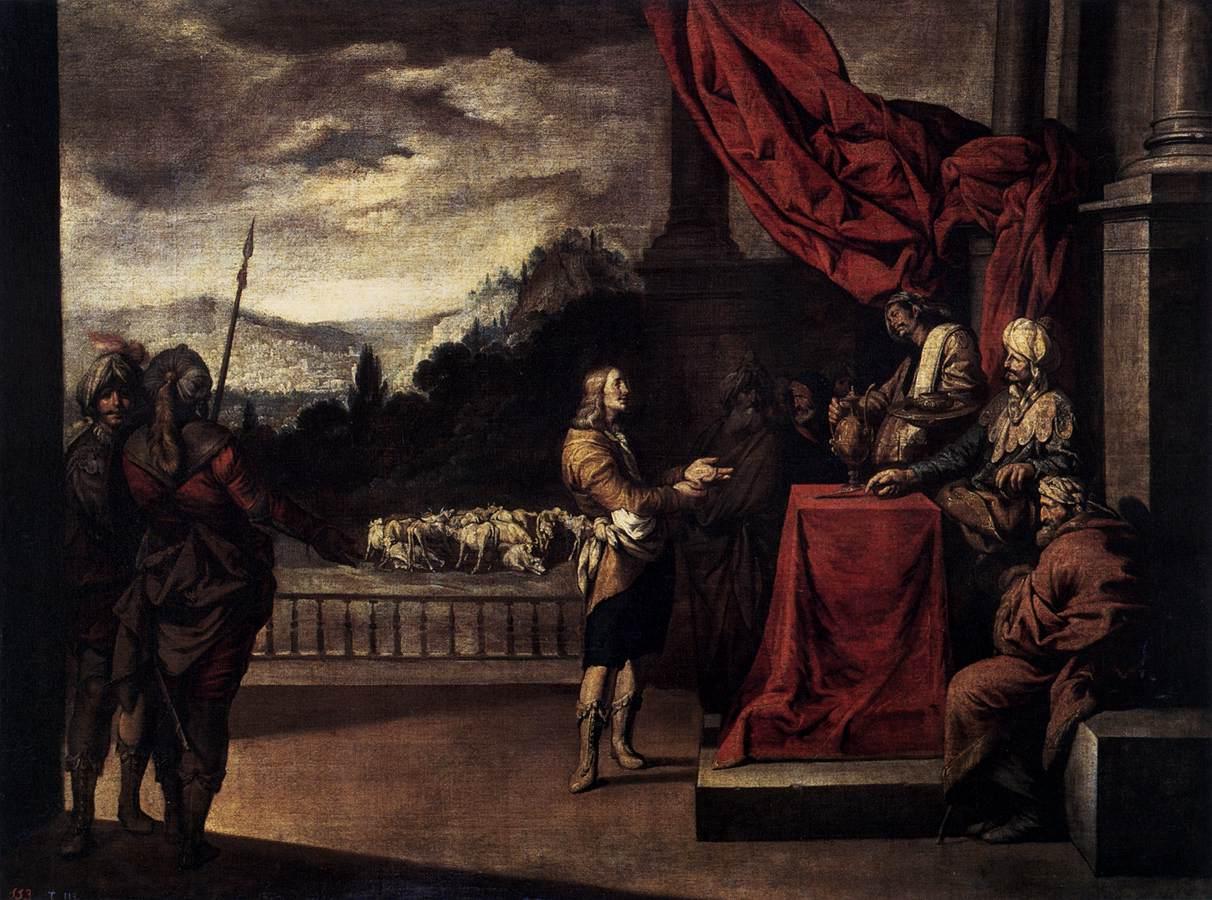

God appears to Jacob "in the visions of the night," and tells him not to be afraid to go to Egypt to see Joseph. So Jacob gathers all the family, sons and grandchildren, and "all the souls of the house of Jacob, which came into Egypt, were threescore and ten." Joseph goes out to meet them in the land of Goshen, and hugs his father and weeps "on his neck a good while."

|

| Salomon de Bray, Joseph Receives His Father and Brothers in Egypt, 1655 |

Chapter 47

So Joseph takes five of his brothers and goes to Pharaoh, whom they ask to be allowed to live in the land of Goshen because of the famine in Canaan. Pharaoh agrees to the request. Then Joseph presents Jacob to Pharaoh, who asks how old Jacob is. He replies that he is one hundred thirty, but he hasn't reached the age that his fathers did. Jacob gives Pharaoh his blessing. So Joseph takes his brothers out to "the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded.

The famine continues, and Joseph gathers all the money in Egypt and Canaan and buys grain with it. When the money is gone, Joseph tells them that he will accept their cattle in payment for grain. With the money and the cattle gone, people say that they have nothing left but their land and their bodies, so Joseph accepts the land as payment for grain, "so the land became Pharaoh's," except for the land held by the priests. Then Joseph gives them seed to plant, with the agreement that every fifth part belongs to Pharaoh.

Jacob lives in the land of Goshen, in Egypt, for seventeen years. When he is one hundred forty-seven, he has Joseph put his hand under his thigh and swear not to bury him in Egypt but to take him back and entomb him with his ancestors.

Chapter 48

When he is about to die, Jacob asks Joseph to bring his two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, for his blessing. Jacob's eyesight is failing, so he can't see the boys, but he tells Joseph that he had thought he would never see Joseph's face now, but "God hath shewed me also thy seed."

|

| Guercino, Jacob Blessing Ephraim and Manasseh, before 1666 |

Chapter 49

Then Jacob calls all of his sons together to prophesy what will happen to each of them. Reuben, he says, is "Unstable as water," and will "not excel; because thou wentest up to thy father's bed; then defiledst thou it." (Reuben had slept with his father's concubine.) Simeon and Levi have "instruments of cruelty ... in their habitations." (They were responsible for the massacre in retaliation for the rape of Dinah.) He curses their anger and says "I will divide them in Jacob and scatter them in Israel."

Judah, on the other hand, "is a lion's whelp," who will dominate his enemies and be a ruler and lawgiver. Zebulon will live by the sea and deal with ships. "Issachar is a strong ass crouching down between two burdens." Dan will be a judge of his people. Gad will be overcome, but will himself overcome in the end. Asher's "bread shall be fat, and he shall yield royal dainties." Naphtali "giveth goodly words." Joseph has overcome what was done to him with the help of God, and will continue to prevail. As for Benjamin, he'll be like a wolf, devouring the prey in the morning and sharing it out at night. Naturally, all of these prophecies have been the subjects of extensive comment and exegesis, considering that they refer to the courses taken by the twelve tribes of Israel.

After reiterating his command (not just a wish) to be buried where Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, and Leah are buried, Jacob gives up the ghost. Joseph has him embalmed, and he is mourned for seventy days before Joseph gets Pharaoh's permission to take the body to the land of Canaan. Everyone, including the cattle, Pharaoh's servants and elders, chariots and horsemen, goes too: "it was a very great company."

After the funeral, Joseph and his brothers return to Egypt, though the brothers worry that, now that their father is dead, Joseph will decide to get even with them for casting him in the pit and selling him into slavery after all. But Joseph tells them not to worry: He isn't God, and it all turned out well in the end. He'll take care of them, he promises.

Joseph lives to be a hundred and ten, and gets to see his great-grandchildren in Ephraim's line and his grandchildren in Manasseh's. He was embalmed, and entombed in Egypt.

Thursday, February 16, 2012

6. Genesis: The Bible, pp. 63-75

Chapter 39

So Joseph is taken to Egypt and sold to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard. Fortunately, Joseph turns out to be an unusually capable servant, so Potiphar makes him overseer of his household. Of course, God has a hand in it: "the LORD blessed the Egyptian's house for Joseph's sake; and the blessing of the LORD was upon all that he had in the house, and in the field."

Joseph was also good-looking, and he attracted the notice of Potiphar's wife, who tried to seduce him. But Joseph argued that he didn't want to betray Potiphar's trust: "There is none greater than I; neither hath he kept any thing from me but thee, because thou art his wife: how then can I do this great wickedness, and sin against God?"

But Potiphar's wife kept at him constantly. One day, Joseph finds himself alone in the house with her, and she grabs hold of his garment, begging him to have sex with her. When he runs away from her, the garment comes off in her hand, and she holds on to it.

So when Potiphar returns, she accuses Joseph of attempted rape, and Potiphar throws him in prison. But with God's help, Joseph impresses the keeper of the prison, and becomes a kind of trusty, in charge of the other prisoners.

Chapter 40

These come to include the chief butler and chief baker to Pharaoh, who do something to offend him. One night, each of these men has a dream. The butler dreams that he saw a vine grow up with three branches, and that he took the ripe grapes, squeezed them, and gave the juice to Pharaoh.

Joseph tells the butler that the three branches are three days, in which time Pharaoh will change his mind about the butler and give him his old job back. He asks the butler to remember him when this happens, and mention him to Pharaoh.

In the baker's dream, he had three white baskets on his head. In the top basket there were "all manner of bake-meats for Pharaoh, and the birds did eat them out of the basket upon my head." Joseph tells him that the three baskets are also three days, but that after the end of three days Pharaoh will have the baker hanged and the birds will eat the baker's flesh.

Sure enough, after three days, the baker is hanged and the butler is restored to his old position. "Yet did not the chief butler remember Joseph, but forgat him."

Chapter 41

Two years later, Pharaoh has a dream. He was standing by the river and seven fat cattle came to feed in the meadow. Then seven skinny cows come to join them, and they eat up the fat ones. Then he dreams again of seven healthy ears of corn that are devoured by seven that are "thin and blasted with the east wind." Pharaoh sends "for all the magicians of Egypt, and all the wise men therof," but none of them can interpret the dreams.

But the butler hears this and remembers Joseph interpreting his dream and that of the baker, so Pharaoh sends for Joseph, who "shaved himself, and changed his raiment, and came in unto Pharaoh." He tells Pharaoh that he doesn't interpret the dreams himself, but "God shall give Pharaoh an answer of peace." So Pharaoh tells Joseph the dreams of the cattle and the ears of corn.

"God hath shewed Pharaoh what is is about to do," Joseph says. "The seven good kine are seven years; and the seven good ears are seven years." The cattle and the ears that devour them are the seven years of famine that will follow. So what Pharaoh needs to do, Joseph tells him, is to find "a man discreet and wise, and set him over the land of Egypt." During the seven good years, the Egyptians need to store up a fifth of all the food grown in Egypt, so they will have it available for the seven years of famine.

Pharaoh tells Joseph he knows just the man for the job:

Joseph is thirty years old when he takes over governing Egypt and seeing to it that preparations are made for the years of famine. He marries Asenath, the daughter of Potipherah, the priest of On, and has two children with her, Manasseh and Ephraim.

Chapter 42

When the famine comes, Joseph opens the storehouses so that Egypt has plenty. Other countries take note and begin coming to Egypt to buy wheat. Joseph's father, Jacob, observes that Egypt has grain for sale, so he sends ten of Joseph's brothers to Egypt to buy it. Only Benjamin, Joseph's youngest brother, stays behind with Jacob, because the old man can't bear the thought of losing him.

Joseph recognizes his brothers when they arrive in Egypt to buy grain from him, but he pretends not to. Instead, he charges them with being spies and throws them in prison. After they have been there for three days, he tells them to leave one of the brothers as a hostage, while he sends them and the grain they need back home. But they must return with their youngest brother to prove that they aren't spies.

The brothers decide that they are being punished by God for what they did to Joseph, and Reuben reminds them that he told them so. Joseph overhears them, but because he has been speaking to them through an interpreter, they don't realize that he understands what they're saying. He has to hide his face from them because he is moved to tears, but he gets control of himself and takes Simeon as hostage, then sends them away.

Without their knowledge, he has the money they have brought to pay for the grain put in the sacks with it. One of the brothers discovers the money when he opens the sack to feed his ass at the inn. They are terrified that they'll be discovered and taken as thieves.

When they get back to the land of Canaan, they tell Jacob what has happened, and that this imposing governor of Egypt has ordered them to return with Benjamin. And when they discover that the money has been placed in all of their sacks, they are more frightened. Jacob is particularly distressed because not only has he lost Joseph and Simeon, but now he is threatened with losing Benjamin. Reuben promises Jacob that he will bring Benjamin back to him, and that if he doesn't Jacob can kill Reuben's own two sons. But Jacob is too terrified of losing Benjamin to agree.

Chapter 43

When the grain they brought from Egypt is gone, however, Jacob tells the brothers to go back and get some more. But Judah reminds Jacob that the governor won't even see them if they don't bring Benjamin with them. Why did you have to tell him you had another brother? Jacob complains. Because he asked, they explain. And Judah insists that he will take good care of Benjamin, and if he doesn't he will "bear the blame for ever."

So Jacob gives in, and adds a gift to give this governor: "a little balm, and a little honey, spices, and myrrh, nuts, and almonds." And they should take twice as much money as they need, in case they're called to account for the money that they unwittingly brought back from the first trip to Egypt.

When they get to Egypt, and Joseph sees that they have brought Benjamin with them, he gives orders that the brothers shall dine with him at his house. The brothers are terrified at the invitation, thinking that it's a trap, and that they'll be seized for taking back the money they brought on the first trip. So when they get to Joseph's house the tell the steward about the money they found in the grain sacks, and that they've brought it back with them. But the steward assures them that it was God's work, and he brings out the hostage Simeon as well.

They are taken in and given water to wash their feet, and their asses are fed. When Joseph arrives, they give him the gift and bow down to him. Joseph asks if their father is still alive, and they assure him he is. And he welcomes Benjamin. Then he hurries off to his own chamber to weep. He returns after washing his face, and they sit down and eat and drink "and were merry with him."

Chapter 44

Joseph gives the steward orders to fill his brothers' sacks and to put the money they had brought in the sacks again. And in Benjamin's sack, he also has the steward put his own silver cup. Then, the next morning, after the brothers have left the city, he tells the steward to go after them and ask, "Wherefore have ye rewarded evil for good?"

The brothers protest at the accusation, and say they can search the sacks. Anyone who has stolen from Joseph's house, they say, can be put to death, and they will become Joseph's slaves. So they start searching the sacks, and when they reach Benjamin's they find the cup. They tear their clothes at the discovery, and return to the city, where they fall at Joseph's feet. Judah says, "God hath found out the iniquity of thy servants," and says they will become Joseph's servants now. But Joseph says he wants only the one in whose sack the cup was found to serve him. The rest can go back to their father.

Judah begs Joseph not to do this: "We have a father, an old man, and a child of his old age, a little one; and his brother is dead, and he alone is left of his mother, and his father loveth him." Jacob will die if Benjamin doesn't return with them, especially after losing his other brother. Judah offers to take Benjamin's place and be Joseph's servant.

Chapter 45

Joseph begins to cry, and sends everyone away except his brothers. Then he tells them, "I am Joseph; doth my father yet live?" The brothers are astonished, but Joseph continues, "I am Joseph your brother, whom ye sold into Egypt." Then he tells them not to regret what they did, because it turned out for the good: "God did send me before you to preserve life" by making the famine less severe than it might have been, and to save their lives by having grain to sell them. "So now it was not you that sent me hither, but God."

So he tells them to hurry back to their father, and tell him that his son is "lord of all Egypt," and to come and live near him in the land of Goshen. He'll take care of them, for there are still five more years of famine to come. He hugs Benjamin and weeps, then kisses all the brothers and weeps with them too. When he hears of this, Pharaoh is pleased as well, and tells Joseph to promise his father and his households that they "shall eat of the fat of the land."

So Joseph gives them wagons and changes of clothing, and gives Benjamin "three hundred pieces of silver, and five changes of raiment." He sends his father "ten asses laden with the good things of Egypt, and ten she asses laden with corn and bread and meat for his father by the way."

So the brothers go back to Jacob and tell him that Joseph is alive, and governor of Egypt. Jacob doesn't believe them at first, but when he sees the wagons Joseph has sent for him, he decides, "I will go and see him before I die."

So Joseph is taken to Egypt and sold to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard. Fortunately, Joseph turns out to be an unusually capable servant, so Potiphar makes him overseer of his household. Of course, God has a hand in it: "the LORD blessed the Egyptian's house for Joseph's sake; and the blessing of the LORD was upon all that he had in the house, and in the field."

Joseph was also good-looking, and he attracted the notice of Potiphar's wife, who tried to seduce him. But Joseph argued that he didn't want to betray Potiphar's trust: "There is none greater than I; neither hath he kept any thing from me but thee, because thou art his wife: how then can I do this great wickedness, and sin against God?"

But Potiphar's wife kept at him constantly. One day, Joseph finds himself alone in the house with her, and she grabs hold of his garment, begging him to have sex with her. When he runs away from her, the garment comes off in her hand, and she holds on to it.

|

| Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, 1640-1645 |

Chapter 40

These come to include the chief butler and chief baker to Pharaoh, who do something to offend him. One night, each of these men has a dream. The butler dreams that he saw a vine grow up with three branches, and that he took the ripe grapes, squeezed them, and gave the juice to Pharaoh.

|

| Benjamin Cuyp, Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of the Butler and Baker, c. 1630 |

In the baker's dream, he had three white baskets on his head. In the top basket there were "all manner of bake-meats for Pharaoh, and the birds did eat them out of the basket upon my head." Joseph tells him that the three baskets are also three days, but that after the end of three days Pharaoh will have the baker hanged and the birds will eat the baker's flesh.

Sure enough, after three days, the baker is hanged and the butler is restored to his old position. "Yet did not the chief butler remember Joseph, but forgat him."

Chapter 41

Two years later, Pharaoh has a dream. He was standing by the river and seven fat cattle came to feed in the meadow. Then seven skinny cows come to join them, and they eat up the fat ones. Then he dreams again of seven healthy ears of corn that are devoured by seven that are "thin and blasted with the east wind." Pharaoh sends "for all the magicians of Egypt, and all the wise men therof," but none of them can interpret the dreams.

But the butler hears this and remembers Joseph interpreting his dream and that of the baker, so Pharaoh sends for Joseph, who "shaved himself, and changed his raiment, and came in unto Pharaoh." He tells Pharaoh that he doesn't interpret the dreams himself, but "God shall give Pharaoh an answer of peace." So Pharaoh tells Joseph the dreams of the cattle and the ears of corn.

|

| Antonio del Castillo, Joseph Explains the Dream of Pharaoh, first half of 17th century |

Pharaoh tells Joseph he knows just the man for the job:

Forasmuch as God hath shewed thee all this, there is none so discreet and wise as thou art:He gives Joseph a ring from his own finger, dresses him in fine linen and puts a gold chain around his neck, then has him ride in the second-best chariot he has, as people bow to him as "ruler over all the land of Egypt."

Thou shalt be over my house, and according unto thy word shall all my people be ruled: only in the throne will I be greater than thou.

|

| Antonio de Castillo, The Triumph of Joseph in Egypt, c.1655 |

Chapter 42

When the famine comes, Joseph opens the storehouses so that Egypt has plenty. Other countries take note and begin coming to Egypt to buy wheat. Joseph's father, Jacob, observes that Egypt has grain for sale, so he sends ten of Joseph's brothers to Egypt to buy it. Only Benjamin, Joseph's youngest brother, stays behind with Jacob, because the old man can't bear the thought of losing him.

Joseph recognizes his brothers when they arrive in Egypt to buy grain from him, but he pretends not to. Instead, he charges them with being spies and throws them in prison. After they have been there for three days, he tells them to leave one of the brothers as a hostage, while he sends them and the grain they need back home. But they must return with their youngest brother to prove that they aren't spies.

The brothers decide that they are being punished by God for what they did to Joseph, and Reuben reminds them that he told them so. Joseph overhears them, but because he has been speaking to them through an interpreter, they don't realize that he understands what they're saying. He has to hide his face from them because he is moved to tears, but he gets control of himself and takes Simeon as hostage, then sends them away.

Without their knowledge, he has the money they have brought to pay for the grain put in the sacks with it. One of the brothers discovers the money when he opens the sack to feed his ass at the inn. They are terrified that they'll be discovered and taken as thieves.

When they get back to the land of Canaan, they tell Jacob what has happened, and that this imposing governor of Egypt has ordered them to return with Benjamin. And when they discover that the money has been placed in all of their sacks, they are more frightened. Jacob is particularly distressed because not only has he lost Joseph and Simeon, but now he is threatened with losing Benjamin. Reuben promises Jacob that he will bring Benjamin back to him, and that if he doesn't Jacob can kill Reuben's own two sons. But Jacob is too terrified of losing Benjamin to agree.

Chapter 43

When the grain they brought from Egypt is gone, however, Jacob tells the brothers to go back and get some more. But Judah reminds Jacob that the governor won't even see them if they don't bring Benjamin with them. Why did you have to tell him you had another brother? Jacob complains. Because he asked, they explain. And Judah insists that he will take good care of Benjamin, and if he doesn't he will "bear the blame for ever."

So Jacob gives in, and adds a gift to give this governor: "a little balm, and a little honey, spices, and myrrh, nuts, and almonds." And they should take twice as much money as they need, in case they're called to account for the money that they unwittingly brought back from the first trip to Egypt.

When they get to Egypt, and Joseph sees that they have brought Benjamin with them, he gives orders that the brothers shall dine with him at his house. The brothers are terrified at the invitation, thinking that it's a trap, and that they'll be seized for taking back the money they brought on the first trip. So when they get to Joseph's house the tell the steward about the money they found in the grain sacks, and that they've brought it back with them. But the steward assures them that it was God's work, and he brings out the hostage Simeon as well.

They are taken in and given water to wash their feet, and their asses are fed. When Joseph arrives, they give him the gift and bow down to him. Joseph asks if their father is still alive, and they assure him he is. And he welcomes Benjamin. Then he hurries off to his own chamber to weep. He returns after washing his face, and they sit down and eat and drink "and were merry with him."

Chapter 44

Joseph gives the steward orders to fill his brothers' sacks and to put the money they had brought in the sacks again. And in Benjamin's sack, he also has the steward put his own silver cup. Then, the next morning, after the brothers have left the city, he tells the steward to go after them and ask, "Wherefore have ye rewarded evil for good?"

The brothers protest at the accusation, and say they can search the sacks. Anyone who has stolen from Joseph's house, they say, can be put to death, and they will become Joseph's slaves. So they start searching the sacks, and when they reach Benjamin's they find the cup. They tear their clothes at the discovery, and return to the city, where they fall at Joseph's feet. Judah says, "God hath found out the iniquity of thy servants," and says they will become Joseph's servants now. But Joseph says he wants only the one in whose sack the cup was found to serve him. The rest can go back to their father.

Judah begs Joseph not to do this: "We have a father, an old man, and a child of his old age, a little one; and his brother is dead, and he alone is left of his mother, and his father loveth him." Jacob will die if Benjamin doesn't return with them, especially after losing his other brother. Judah offers to take Benjamin's place and be Joseph's servant.

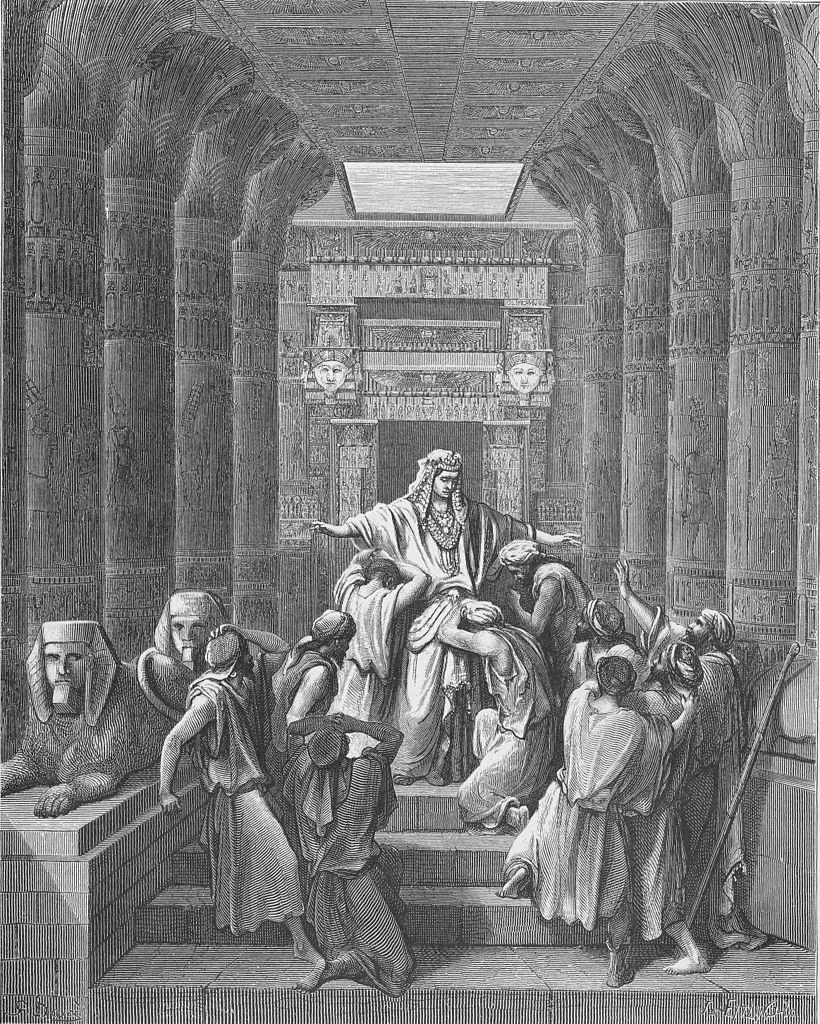

Chapter 45

Joseph begins to cry, and sends everyone away except his brothers. Then he tells them, "I am Joseph; doth my father yet live?" The brothers are astonished, but Joseph continues, "I am Joseph your brother, whom ye sold into Egypt." Then he tells them not to regret what they did, because it turned out for the good: "God did send me before you to preserve life" by making the famine less severe than it might have been, and to save their lives by having grain to sell them. "So now it was not you that sent me hither, but God."

|

| Gustave Doré, Joseph Reveals Himself to His Brothers, 1866 |

So he tells them to hurry back to their father, and tell him that his son is "lord of all Egypt," and to come and live near him in the land of Goshen. He'll take care of them, for there are still five more years of famine to come. He hugs Benjamin and weeps, then kisses all the brothers and weeps with them too. When he hears of this, Pharaoh is pleased as well, and tells Joseph to promise his father and his households that they "shall eat of the fat of the land."

So Joseph gives them wagons and changes of clothing, and gives Benjamin "three hundred pieces of silver, and five changes of raiment." He sends his father "ten asses laden with the good things of Egypt, and ten she asses laden with corn and bread and meat for his father by the way."

So the brothers go back to Jacob and tell him that Joseph is alive, and governor of Egypt. Jacob doesn't believe them at first, but when he sees the wagons Joseph has sent for him, he decides, "I will go and see him before I die."

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

5. Genesis: The Bible, pp. 52-63

Chapter 32

Jacob sends word to Esau that he is returning with "oxen, and asses, flocks, and menservants, and womenservants. And he gets word back that Esau is coming to meet him with four hundred men. Since the last he heard, twenty years ago, is that his brother wanted to kill him, Jacob is "greatly afraid and distressed" by the news. So he divides his people and his flocks into two groups; if Esau attacks one of the groups, at least the others will escape. He also prays to God for deliverance from his brother.

Then he prepares a present for Esau: "Two hundred she goats, and twenty he goats, two hundred ewes, and twenty rams, Thirty milch camels with their colts, forty kine, and ten bulls, twenty she asses, and ten foals." He puts his servants in charge of each drove of animals, and tells them that if Esau meets them, they should tell him it's a present for him. Then he sends his wives and his children ahead, and spends the night alone.

During the night, he wrestles with a man until dawn. The man, evidently an angel, doesn't win, but he touches "the hollow of his thigh" and puts it "out of joint." Finally the man asks Jacob to let him go, but Jacob says he won't until he gets a blessing. So he says, "Thy name shall be called no more Jacob, but Israel: for as a prince hast thou power with God and with men, and hast prevailed."

Because of the disjointed thigh, Jacob limps away. "Therefore the children of Israel eat not of the sinew which shrank, which is upon the hollow of the thigh, unto this day."

Now he sees Esau and his four hundred men coming, so he gets his family ready, putting the handmaids and their children in the forefront, then Leah and her children, and finally Rachel and Joseph. But to his surprise, Esau runs to meet him, hugs and kisses him, and they both weep.

Esau asks about all the animals that were being sent before him, and Jacob explains that they are a gift, "to find grace in the sight of my lord." But Esau says he has plenty and to keep what he has. Jacob insists, however, and and Esau accepts.

Esau suggests that they go on together, but Jacob points out that there are small children and young animals with him, so it would be better if he came along at a slower pace. So Esau goes back to Seir, and Jacob makes his way to Succoth where he builds a house and barns. Then he goes to Shechem and pitches a tent outside of the city.

Chapter 34

Dinah, Jacob's daughter by Leah, goes "out to see the daughters of the land," which I guess means she goes into the city of Shechem to visit some new acquaintances. While she's there, however, she is spotted by the prince named Shechem, who "took her, and lay with her, and defiled her," which seems to mean that she was raped. Then he decides he wants to marry her, to he tells his father, Hamor, to arrange it for him.

Jacob hears about the rape of Dinah while his sons are out tending the cattle. Hamor arrives to try to arrange her marriage to Shechem, as well as Jacob's granddaughters with other men of the city. Jacob's sons are furious when they hear how their sister was treated, and they insist that if these marriages are to take place, all the men of the city must be circumcised.

Hamor and Shechem are willing, and they tell the men of the city about the deal. They agree to it as well. But three days after all the men were circumcised, "when they were sore," two of Jacob's sons, Simeon and Levi, enter the city and slaughter all the men, including Hamor and Shechem. They take all the cattle in the city, along with the women and children.

Jacob isn't happy at all, telling Simeon and Levi, "Ye have troubled me to make me to stink among the inhabitants of the land." He fears that the other Canaanites will rise up against him because of their slaughter of the Shechemites. But Simeon and Levi protest, "She he [presumably Shechem] deal with our sister as with an harlot?"

Chapter 35

So Jacob decides to move to Beth-el, and tells everyone to leave any "strange gods," i.e. idols, behind. There God appears to him again, and tells Jacob his name is now Israel, and repeats his promise that his descendants will be numerous and will include kings.

Then they journey from Beth-el to Ephrath, which is now Bethlehem, and along the way Rachel gives birth to Benjamin, but dies in childbirth. This makes a total of twelve sons of Jacob, or Israel: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun by Leah; Joseph and Benjamin by Rachel; Dan and Naphtali by Bilhah, Rachel's handmaid; and Gad and Asher by Zilpah, Leah's handmaid.

Jacob goes to see his father, Isaac, in Hebron, and Isaac dies, age one hundred eighty, and is buried by Esau and Jacob.

Chapter 36

Now there's a list of the descendants of Esau, who becomes the father of the Edomites. Esau and Jacob have to part ways because they are so rich and have so much cattle that there isn't enough land for both of them to live in the same place.

Chapter 37

When Joseph is seventeen, he gives his father an "evil report" about the doings of the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah. Joseph is Israel's favorite, and he has a "coat of many colours" made for him. This doesn't endear him to his brothers, and Joseph makes things worse by telling them of a dream he had: They were "binding sheaves in the field," and his sheaf stood upright while their sheaves bowed down to it.

When his brothers go off to Shechem to feed the flocks there, Israel sends Joseph to see how they are getting along. A man Joseph meets tells them they are at Dothan, so Joseph goes there. But when the brothers see him coming, they start plotting to kill "this dreamer." They plan to throw his body into a pit and say a wild beast ate him. Reuben, however, says they shouldn't kill him, but just throw him into the pit.

So when Joseph gets there, the brothers strip him of his coat of many colors and throw him into the pit. While the brothers are eating, a caravan of Ishmeelites, carrying spices to Egypt, passes by. So Judah suggests that they should make some money by selling Joseph to the Ishmeelites, who agree to pay them twenty pieces of silver.

Reuben, who was away while this deal was being made, returns to find Joseph gone, and realizes that they need a story to tell their father. So they take the coat of many colors and dip it in some goat's blood. When they take it to their father, he recognizes it and concludes that "an evil beast hath devoured him." He tears his clothes and puts on sackcloth, and refuses to be consoled.

Joseph is taken to Egypt and sold to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard.

Chapter 38

Judah has had three children by a woman named Shuah. Their names are Er, Onan, and Shelah. He arranges a marriage of Er to a woman named Tamar, but Er is wicked and God kills him. So Judah tells Onan to marry his brother's wife. But Onan knows that the child won't be his, so when he has sex with Tamar, he resorts to coitus interruptus, spilling his seed on the ground, "lest that he should give seed to his brother." (Masturbation is sometimes, and apparently erroneously, called "onanism.") But God doesn't like his doing this, so he kills Onan, too.

Judah then tells Tamar to wait until Shelah is grown, so Tamar goes to live with her father in the meantime. After Judah's wife dies, he goes to shear sheep at Timnath. Tamar hears this, and having realized that Shelah must be grown now and she hasn't been married to him, she puts on a veil and goes to sit by the road on the way to Timnath. Judah sees her and thinks she's a prostitute because her face is covered.

She asks what he will pay her, and he tells her he'll send her a kid from the flock he's going to shear. But she wants a pledge from him that he'll deliver the kid, so she asks for his signet, his bracelets, and the staff he is carrying. He gives them to her, sleeps with her, and she gets pregnant.

Judah sends a friend to deliver the kid, but he can't find "the harlot, that was openly by the way side," and people tell him there is no such harlot. So the friend goes back and tells Judah that he can't find her. Then about three months later, Judah hears that his daughter-in-law is "with child by whoredom," so Judah sends for her, intending to have her burnt.

When she arrives, she shows him the signet, the bracelets, and the staff, and tells him that they belong to the father of her child. He realizes what has happened, and says, "She hath been more righteous than I; because that I gave her not to Shelah my son."

Tamar turns out to be pregnant with twins, and during labor, when the midwife sees one put out his hand, she ties a scarlet thread around it, "saying, This came out first." But the baby pulls his hand back in and his brother comes out first. He is named Pharez. Then the other baby is born with the scarlet thread on his hand and is called Zarah.

Jacob sends word to Esau that he is returning with "oxen, and asses, flocks, and menservants, and womenservants. And he gets word back that Esau is coming to meet him with four hundred men. Since the last he heard, twenty years ago, is that his brother wanted to kill him, Jacob is "greatly afraid and distressed" by the news. So he divides his people and his flocks into two groups; if Esau attacks one of the groups, at least the others will escape. He also prays to God for deliverance from his brother.

Then he prepares a present for Esau: "Two hundred she goats, and twenty he goats, two hundred ewes, and twenty rams, Thirty milch camels with their colts, forty kine, and ten bulls, twenty she asses, and ten foals." He puts his servants in charge of each drove of animals, and tells them that if Esau meets them, they should tell him it's a present for him. Then he sends his wives and his children ahead, and spends the night alone.

During the night, he wrestles with a man until dawn. The man, evidently an angel, doesn't win, but he touches "the hollow of his thigh" and puts it "out of joint." Finally the man asks Jacob to let him go, but Jacob says he won't until he gets a blessing. So he says, "Thy name shall be called no more Jacob, but Israel: for as a prince hast thou power with God and with men, and hast prevailed."

|

| Eugène Delacroix, Jacob Wrestling With the Angel, 1854-1861 |

Now he sees Esau and his four hundred men coming, so he gets his family ready, putting the handmaids and their children in the forefront, then Leah and her children, and finally Rachel and Joseph. But to his surprise, Esau runs to meet him, hugs and kisses him, and they both weep.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau, 1625-28 |

Esau suggests that they go on together, but Jacob points out that there are small children and young animals with him, so it would be better if he came along at a slower pace. So Esau goes back to Seir, and Jacob makes his way to Succoth where he builds a house and barns. Then he goes to Shechem and pitches a tent outside of the city.

Chapter 34

Dinah, Jacob's daughter by Leah, goes "out to see the daughters of the land," which I guess means she goes into the city of Shechem to visit some new acquaintances. While she's there, however, she is spotted by the prince named Shechem, who "took her, and lay with her, and defiled her," which seems to mean that she was raped. Then he decides he wants to marry her, to he tells his father, Hamor, to arrange it for him.

Jacob hears about the rape of Dinah while his sons are out tending the cattle. Hamor arrives to try to arrange her marriage to Shechem, as well as Jacob's granddaughters with other men of the city. Jacob's sons are furious when they hear how their sister was treated, and they insist that if these marriages are to take place, all the men of the city must be circumcised.

Hamor and Shechem are willing, and they tell the men of the city about the deal. They agree to it as well. But three days after all the men were circumcised, "when they were sore," two of Jacob's sons, Simeon and Levi, enter the city and slaughter all the men, including Hamor and Shechem. They take all the cattle in the city, along with the women and children.

Jacob isn't happy at all, telling Simeon and Levi, "Ye have troubled me to make me to stink among the inhabitants of the land." He fears that the other Canaanites will rise up against him because of their slaughter of the Shechemites. But Simeon and Levi protest, "She he [presumably Shechem] deal with our sister as with an harlot?"

Chapter 35

So Jacob decides to move to Beth-el, and tells everyone to leave any "strange gods," i.e. idols, behind. There God appears to him again, and tells Jacob his name is now Israel, and repeats his promise that his descendants will be numerous and will include kings.

Then they journey from Beth-el to Ephrath, which is now Bethlehem, and along the way Rachel gives birth to Benjamin, but dies in childbirth. This makes a total of twelve sons of Jacob, or Israel: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun by Leah; Joseph and Benjamin by Rachel; Dan and Naphtali by Bilhah, Rachel's handmaid; and Gad and Asher by Zilpah, Leah's handmaid.

Jacob goes to see his father, Isaac, in Hebron, and Isaac dies, age one hundred eighty, and is buried by Esau and Jacob.

Chapter 36

Now there's a list of the descendants of Esau, who becomes the father of the Edomites. Esau and Jacob have to part ways because they are so rich and have so much cattle that there isn't enough land for both of them to live in the same place.

Chapter 37

When Joseph is seventeen, he gives his father an "evil report" about the doings of the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah. Joseph is Israel's favorite, and he has a "coat of many colours" made for him. This doesn't endear him to his brothers, and Joseph makes things worse by telling them of a dream he had: They were "binding sheaves in the field," and his sheaf stood upright while their sheaves bowed down to it.

And his brethren said to him, Shalt thou indeed reign over us? or shalt thou indeed have dominion over us? And they hated him yet the more for his dreams, and for his words.Then he tells them about another dream in which "the sun and the moon and the eleven stars made obeisance to me." This dream displeases his father, too: "Shall I and thy mother and thy brethren indeed come to bow down ourselves to thee to the earth?"

When his brothers go off to Shechem to feed the flocks there, Israel sends Joseph to see how they are getting along. A man Joseph meets tells them they are at Dothan, so Joseph goes there. But when the brothers see him coming, they start plotting to kill "this dreamer." They plan to throw his body into a pit and say a wild beast ate him. Reuben, however, says they shouldn't kill him, but just throw him into the pit.

So when Joseph gets there, the brothers strip him of his coat of many colors and throw him into the pit. While the brothers are eating, a caravan of Ishmeelites, carrying spices to Egypt, passes by. So Judah suggests that they should make some money by selling Joseph to the Ishmeelites, who agree to pay them twenty pieces of silver.

Reuben, who was away while this deal was being made, returns to find Joseph gone, and realizes that they need a story to tell their father. So they take the coat of many colors and dip it in some goat's blood. When they take it to their father, he recognizes it and concludes that "an evil beast hath devoured him." He tears his clothes and puts on sackcloth, and refuses to be consoled.

|

| Giovanni Andrea de Ferrari, Joseph's Coat Brought to Jacob, c. 1640 |

Chapter 38

Judah has had three children by a woman named Shuah. Their names are Er, Onan, and Shelah. He arranges a marriage of Er to a woman named Tamar, but Er is wicked and God kills him. So Judah tells Onan to marry his brother's wife. But Onan knows that the child won't be his, so when he has sex with Tamar, he resorts to coitus interruptus, spilling his seed on the ground, "lest that he should give seed to his brother." (Masturbation is sometimes, and apparently erroneously, called "onanism.") But God doesn't like his doing this, so he kills Onan, too.

Judah then tells Tamar to wait until Shelah is grown, so Tamar goes to live with her father in the meantime. After Judah's wife dies, he goes to shear sheep at Timnath. Tamar hears this, and having realized that Shelah must be grown now and she hasn't been married to him, she puts on a veil and goes to sit by the road on the way to Timnath. Judah sees her and thinks she's a prostitute because her face is covered.

| School of Rembrandt, Judah and Tamar, c. 1650-1660 |

Judah sends a friend to deliver the kid, but he can't find "the harlot, that was openly by the way side," and people tell him there is no such harlot. So the friend goes back and tells Judah that he can't find her. Then about three months later, Judah hears that his daughter-in-law is "with child by whoredom," so Judah sends for her, intending to have her burnt.

When she arrives, she shows him the signet, the bracelets, and the staff, and tells him that they belong to the father of her child. He realizes what has happened, and says, "She hath been more righteous than I; because that I gave her not to Shelah my son."

Tamar turns out to be pregnant with twins, and during labor, when the midwife sees one put out his hand, she ties a scarlet thread around it, "saying, This came out first." But the baby pulls his hand back in and his brother comes out first. He is named Pharez. Then the other baby is born with the scarlet thread on his hand and is called Zarah.

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

4. Genesis: The Bible, pp. 40-52

Chapter 26

There is a famine, but God tells Isaac not to go to Egypt to avoid it. So Isaac lives in Gerar, where like Abraham he tells people that Rebekah is his sister, so they won't kill him and take her. But Abimelech, the king of the Philistines, looks out of of the window one day and sees Isaac "sporting with Rebekah his wife." (No kidding, that's what it says.) So Abimelech calls Isaac in and asks how come he said she was his sister when she's obviously his wife? Isaac explains that he was afraid he'd get killed because she's so beautiful, but Abimelech worries that one of his people might have slept with Rebekah under the impression that she was available, and thereby "brought guiltiness upon us." So he puts out the word that nobody is to touch Isaac or Rebekah under pain of death.

Isaac gets rich, and the envious Philistines start filling up the wells Abraham had dug, so Abimelech tells him to move on, "for thou art much mightier than we." Isaac pitches his tent in the valley of Gerar and digs out the wells that had been filled up, but the herdsmen of Gerar fight with Isaac's herdsmen over the water, so Isaac moves on to Beer-sheba, where Abimelech makes a covenant with him, promising to leave him alone.

When Esau is forty, he marries two Hittite women, Judith and Bashemath, but Isaac and Rebekah are unhappy about it.

Chapter 27

Isaac grows old and blind, and before he dies he asks Esau, his favorite son, to hunt some venison and make his favorite dish out of it. Then, he says, he will give him his blessing. But Rebekah, who favors Jacob, overhears this, and tells Jacob to kill two goats and she will make Isaac's favorite dish from them before Esau returns with the venison. "And thou shalt bring it to thy father, that he may eat, and that he may bless thee before his death."

Jacob points out that Esau is hairy, whereas he is smooth, so that if Isaac touches him, he'll realize that he's being tricked. "I shall bring a curse upon me, and not a blessing." Not to worry, Rebekah says. "Upon me be thy curse, my son: only obey my voice, and go fetch me them." So Jacob does as he's told, and Rebekah prepares the meat. She also takes some of Esau's clothes and puts them on Jacob, and covers his hands and the back of his neck with the goatskins.

Jacob goes to his father with the meat and says, "I am Esau thy firstborn; I have done according as thou badest me: arise, I pray thee, sit and eat of my venison, that thy soul may bless me." Isaac wonders at how quickly Esau hunted and killed the animal, but Jacob claims it was "Because the LORD thy God brought it to me." Isaac still has his doubts, and asks Jacob to come closer "that I may feel thee, my son, whether thou be my very son Esau or not." So Jacob comes closer, and Isaac touches him: "The voice is Jacob's voice, but the hands are the hands of Esau," he says.

After he eats, Isaac asks Jacob to come closer so he can kiss him, and he smells the clothes Rebekah has taken from Esau. Isaac says, "See, the smell of my son is as the smell of a field which the LORD hath blessed."

Esau is naturally furious: He sold his birthright to Jacob for some lentils, and now his brother has stolen Isaac's blessing. Isaac admits, "I have made him thy lord, and all his brethren have I given to him for servants; and with corn and wine have I sustained him: and what shall I do now unto thee, my son?" Esau asks if there's any blessing left over, but there isn't much.

Chapter 28

Isaac, too, doesn't want Jacob marrying any of the local girls, so he sends him off to marry one of his cousins: "the daughters of Laban thy mother's brother." Esau, still smarting from Jacob's dirty trick, admits that his marriages haven't exactly made his family happy, so he marries his aunt: "Mahalath the daughter of Ishmael Abraham's son."

When Jacob stops for the night on his way to Laban's, he takes some stones for a pillow and has a dream of "a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it."

From the top of the ladder, God calls down that he is giving Jacob the land where he is sleeping and will spread his seed in all directions. He promises not to leave Jacob, and to bring him back to this land. So when Jacob wakes up he takes the stones he had been using as a pillow and piles them up in a pillar and pours oil on it. He calls the place Beth-el, and promises that it "shall be God's house."

Chapter 29

When Jacob gets near Haran, he finds some sheep waiting to be watered at a well with a great stone over its mouth. While he is talking with the shepherds, Laban's daughter Rachel arrives with her father's sheep, so Jacob rolls away the stone so they can be watered. Then he kisses Rachel and tells her that he is Rebekah's son, so she runs to fetch her father, Laban, who comes out and welcomes Jacob.

Laban has two daughters: Rachel is the younger, and Leah the elder. "Leah was tender eyed; but Rachel was beautiful and well favoured." So Jacob strikes a deal with Laban: He will serve Laban for seven years and marry Rachel. Jacob is so in love with Rachel that the seven years go by like just a few days.

When the time is up, Jacob asks to be married to Rachel, and Laban holds a feast. But after it he brings Leah to Jacob's tent in the dark. When Jacob discovers in the morning that he has slept with Leah instead, he asks what Laban has done to him. Laban explains that it's not the custom of their country to marry the younger daughter first. But if Jacob will stay with Leah for a week, then he'll give him Rachel as well -- as long as he serves Laban another seven years. So Jacob gives in and agrees.

God doesn't like it that Jacob despises Leah, so he sees to it that Leah gives birth while Rachel remains barren. Leah's first child with Jacob is Reuben, then she has another named Simeon, followed by Levi and Judah.

Chapter 30

Rachel is angry that Jacob keeps getting Leah pregnant but not her, but Jacob blames it on the Lord. So she gives Jacob her handmaid, Bilhah, hoping that she'll conceive and Rachel will have a child to raise. Bilhah gets pregnant and Rachel names the child Dan. Then Bilhah has another that Rachel calls Naphtali. Now Leah wants more children, so she gives Jacob her handmaid Zilpah, who produces a son Leah names Gad. Then Zilpah has another one that Leah calls Asher.

Leah's son Reuben finds some mandrakes and takes them to his mother. When Rachel sees them, she asks for them, and agrees to let Leah have sex with Jacob in exchange for the mandrakes. Leah conceives, and names this son Issachar. Then she has another son with Jacob that she names Zebulun, followed by a daughter, whom she calls Dinah.

Finally, God decides to let Rachel have a child, and she names him Joseph. Then Jacob decides it's time to move all of this family back to where he came from. Laban wants them to stay, but asks what Jacob wants in the way of wages. Jacob points out that he has greatly increased Laban's herd of cattle since he has been there, so he proposes to go through the heard and keep "all the speckled and spotted cattle, and all the brown cattle among the sheep, and the spotted and speckled among the goats."

But then Jacob pulls another one of his tricks, like the one he used to steal Esau's blessing. He takes "rods of green poplar, and of the hazel and chestnut tree," and peels the bark off of them in stripes. Then he puts the rods at the watering troughs where the flocks drink. "And the flocks conceived before the rods, and brought forth cattle ringstraked, speckled, and spotted. He also shows the rods to the stronger cattle, but not to the weaker ones, so that "the feebler were Laban's, and the stronger Jacob's."

Chapter 31

Laban's sons are mightily ticked off that Jacob is getting away with so much of their father's cattle, and Jacob can tell that Laban shares their anger. The Lord suggests that Jacob should get started on his move, and promises to be with him along the way. So Jacob tells Rachel and Leah to hurry and get ready. Their father, he tells him, has changed his mind about Jacob's wages ten times, but the Lord has seen to it that Jacob prospered from it. God, he says, is the one who made the cattle speckled and spotted: "Thus God hath taken away the cattle of your father, and given them to me." He claims that God appeared to him in a dream and told him that he did this because he saw how Laban mistreated Jacob. "I am the God of Beth-el, where thou anointedst the pillar, and where thou vowedst a vow unto me: now arise, get thee out from this land, and return unto the land of thy kindred."

When they have left, Laban discovers that Rachel has taken his "images" -- his idols. So Laban pursues Jacob and catches up with him at Mount Gilead. He claims that Jacob stole away "secretly," without letting Laban give him a proper send-off, "with mirth, and with songs, with tabret, and with harp," and without letting him kiss his daughters and his grandsons goodbye. He says that Jacob's God spoke to him and told him not to do Jacob harm, but he wants to know why Jacob has stolen his gods.

Jacob replies that he was afraid Laban might try to take his daughters away from him, but he doesn't know anything about the idols. So Laban searches Jacob's and Leah's tents and doesn't find the idols. Then he goes to Rachel's tent, but "Rachel had taken the images, and put them in the camel's furniture, and sat upon them. And Laban searched all the tent, but found them not."

Jacob then upbraids Laban for his suspicions, telling him he has spent twenty years in Laban's house, serving him fourteen years for his daughters and six years tending his cattle, and Laban has changed his wages ten times. "God hath seen my affliction and the labour of my hands, and rebuked thee yesternight."

So Laban agrees to a covenant with Jacob, and agrees that they won't bother each other anymore, as long as Jacob doesn't abuse his daughters or take other wives. The next morning, Laban kisses his daughters goodbye and goes home.

There is a famine, but God tells Isaac not to go to Egypt to avoid it. So Isaac lives in Gerar, where like Abraham he tells people that Rebekah is his sister, so they won't kill him and take her. But Abimelech, the king of the Philistines, looks out of of the window one day and sees Isaac "sporting with Rebekah his wife." (No kidding, that's what it says.) So Abimelech calls Isaac in and asks how come he said she was his sister when she's obviously his wife? Isaac explains that he was afraid he'd get killed because she's so beautiful, but Abimelech worries that one of his people might have slept with Rebekah under the impression that she was available, and thereby "brought guiltiness upon us." So he puts out the word that nobody is to touch Isaac or Rebekah under pain of death.

Isaac gets rich, and the envious Philistines start filling up the wells Abraham had dug, so Abimelech tells him to move on, "for thou art much mightier than we." Isaac pitches his tent in the valley of Gerar and digs out the wells that had been filled up, but the herdsmen of Gerar fight with Isaac's herdsmen over the water, so Isaac moves on to Beer-sheba, where Abimelech makes a covenant with him, promising to leave him alone.

When Esau is forty, he marries two Hittite women, Judith and Bashemath, but Isaac and Rebekah are unhappy about it.

Chapter 27

Isaac grows old and blind, and before he dies he asks Esau, his favorite son, to hunt some venison and make his favorite dish out of it. Then, he says, he will give him his blessing. But Rebekah, who favors Jacob, overhears this, and tells Jacob to kill two goats and she will make Isaac's favorite dish from them before Esau returns with the venison. "And thou shalt bring it to thy father, that he may eat, and that he may bless thee before his death."

Jacob points out that Esau is hairy, whereas he is smooth, so that if Isaac touches him, he'll realize that he's being tricked. "I shall bring a curse upon me, and not a blessing." Not to worry, Rebekah says. "Upon me be thy curse, my son: only obey my voice, and go fetch me them." So Jacob does as he's told, and Rebekah prepares the meat. She also takes some of Esau's clothes and puts them on Jacob, and covers his hands and the back of his neck with the goatskins.

|

| Govert Flinck, Isaac Blessing Jacob, 1638 |

After he eats, Isaac asks Jacob to come closer so he can kiss him, and he smells the clothes Rebekah has taken from Esau. Isaac says, "See, the smell of my son is as the smell of a field which the LORD hath blessed."

Therefore God give thee of the dew of heaven, and the fatness of the earth, and plenty of corn and wine;Then Esau comes back from his hunting trip, prepares the meat, and brings it to Isaac, who is confused and astonished; he "trembled very exceedingly." Isaac tells Esau what has happened: "Thy brother came with subtilty, and hath taken away thy blessing." (That word "subtilty" is interesting: The only other "subtil" creature we have heard of is the serpent who tempted Eve.)

Let people serve thee, and nations bow down to thee: be lord over thy brethren, and let thy mother's sons bow down to thee: cursed be every one that curseth thee, and blessed be he that blesseth thee.

Esau is naturally furious: He sold his birthright to Jacob for some lentils, and now his brother has stolen Isaac's blessing. Isaac admits, "I have made him thy lord, and all his brethren have I given to him for servants; and with corn and wine have I sustained him: and what shall I do now unto thee, my son?" Esau asks if there's any blessing left over, but there isn't much.

Behold, thy dwelling shall be the fatness of the earth, and of the dew of heaven from above;Esau vows to kill Jacob as soon as the period of mourning after their father's death is over, so Rebekah tells Jacob to flee to her brother Laban's. Besides, she's still pissed off because of the Hittite women Esau married, and doesn't want Jacob to marry one of them too.

And by thy sword shalt thou live, and shalt serve thy brother; and it shall come to pass when thou shalt have the dominion, that thou shalt break his yoke from off thy neck.

Chapter 28

Isaac, too, doesn't want Jacob marrying any of the local girls, so he sends him off to marry one of his cousins: "the daughters of Laban thy mother's brother." Esau, still smarting from Jacob's dirty trick, admits that his marriages haven't exactly made his family happy, so he marries his aunt: "Mahalath the daughter of Ishmael Abraham's son."

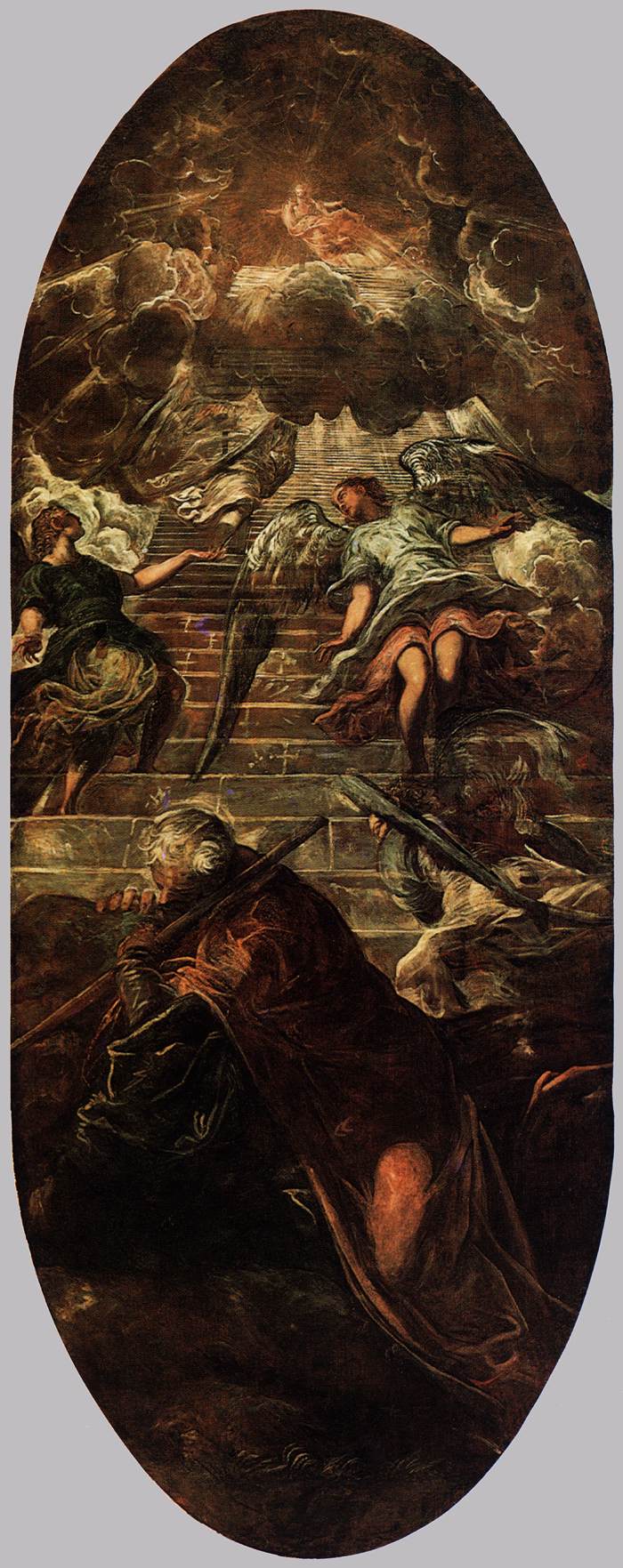

When Jacob stops for the night on his way to Laban's, he takes some stones for a pillow and has a dream of "a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it."

|

| Jacopo Tintoretto, Jacob's Ladder, 1577-78 |

Chapter 29

When Jacob gets near Haran, he finds some sheep waiting to be watered at a well with a great stone over its mouth. While he is talking with the shepherds, Laban's daughter Rachel arrives with her father's sheep, so Jacob rolls away the stone so they can be watered. Then he kisses Rachel and tells her that he is Rebekah's son, so she runs to fetch her father, Laban, who comes out and welcomes Jacob.