|

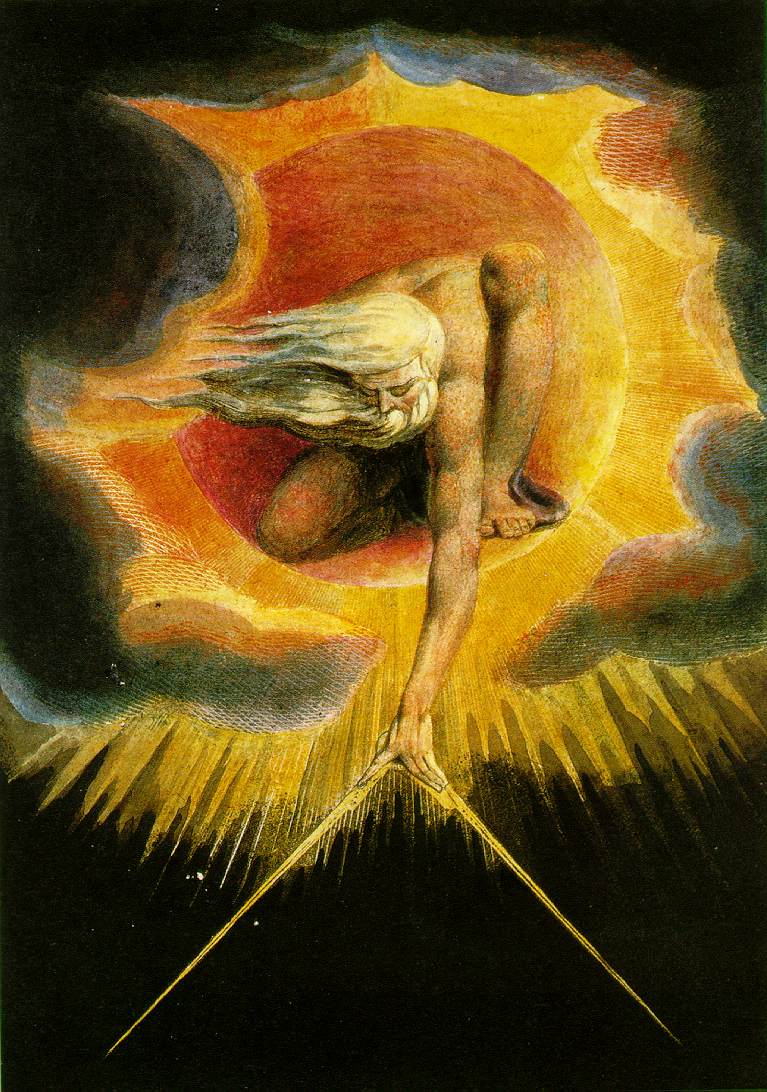

| William Blake, Ancient of Days, 1794 |

"In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth...." Except, if it was the beginning, where did this "God" come from? That's the puzzle in all cosmologies: How did something get there out of nothing? Even with a big bang theory, where did the stuff come from that went boom? I guess the usual answer to the biblical version is that God is a spirit: "The Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters," we read in the next verse. (Except where did these "waters" come from?) I guess the solution is that "spirit" somehow created "matter," which is what this creation myth is dealing with: the beginning of matter.

In any case, "the earth was without form and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep." So there is now "something" there to work with, a chaos of matter, perhaps a tumble of atoms, to put it in Lucretian terms. It seems to have been liquid: "the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters." And this spirit turned on the light, dividing it from darkness, and "called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night." The first step in bringing order out of chaos: Lights on, lights off.

Also, significantly, giving things names: Day and Night. And once he's set up a regular alternation of the two, he has created the first day. (Not the first capital-letter Day, notice.)

Then he set himself to dividing these waters with a "firmament," some kind of structure that separates them into two layers. There's the water up there and the water down here. Again with the naming: "God called the firmament Heaven." And this took another day.

Next, he moved "the waters under the heaven" and revealed dry land. Which I guess means that back when the whole thing was chaos, the land was all mixed in with the waters, sort of a primordial soup, and on this third day God separated out the solids from the liquid. And he named them: Earth and Seas. As when he created light, he "saw that it was good." Nothing like a job well done. But he's not through yet: He has the earth produce grass and fruit trees and has both yield seed so they can self-perpetuate. This is a bigger step than it sounds like: God has just created life. And all of this on the third day.

On the fourth day, he goes about creating "lights," which seems to be something different from creating light, though it's not quite clear how. After all, he has already created Day and Night and evenings and mornings so that he could count off three days. But I guess what he does here is systematize the whole thing, so that it can proceed automatically, making "two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also." And he likes what he's done here, too.

Animal life is next: fish and birds and "great whales." (The last seem to be neither fish nor fowl in the scheme of things.) And seeing "that it was good," he blesses them and tells them, "Be fruitful, and multiply," which he's shortly going to be instructing humankind to do as well.

On the sixth day he has "the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind." He started with creatures that live in water and creatures that fly in the air, so now it's time to work on the land animals. Why the priority here? He makes each of these land animals "after his/their kind," which I think means each as a distinct species, not a whole bunch of higgledy-piggledy individuals, like one dog with a set of antlers and another with eight legs. In any case, he once again sees "that it was good."

But wait, he's not finished:

And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping; thing that creepeth upon the earth.Okay, a few things to puzzle about here. "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness." Who's this "us" and "our"? Who's he talking to? Or is this just the divine equivalent of the royal We? Also, how come a spirit has an "image"? We haven't been told that God has eyes and ears and nose and teeth and two arms and two legs, but that is surely what it sounds like here. Also, isn't this a bit abrupt? Where's the business about creating Adam first and then Eve? It's coming, of course, but in this account the specifics of creating humans don't seem so terribly important. Notice, too, that this account doesn't specify just one man and one woman, but leaves open the possibility that God created a whole bunch of people at once.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

So God tells these human beings, as he did the fish and the birds, "Be fruitful, and multiply." But he also gives them "dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth." Lots of us are not happy with this concept of "dominion," but it seems to be a fait accompli. On the other hand, God seems to be a vegetarian, telling his human beings, "I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat." And he has done the same thing, he says, for the animals: "I have given every green herb for meat."

So he sees "every thing that he had made, and behold, it was very good."

Chapter 2

|

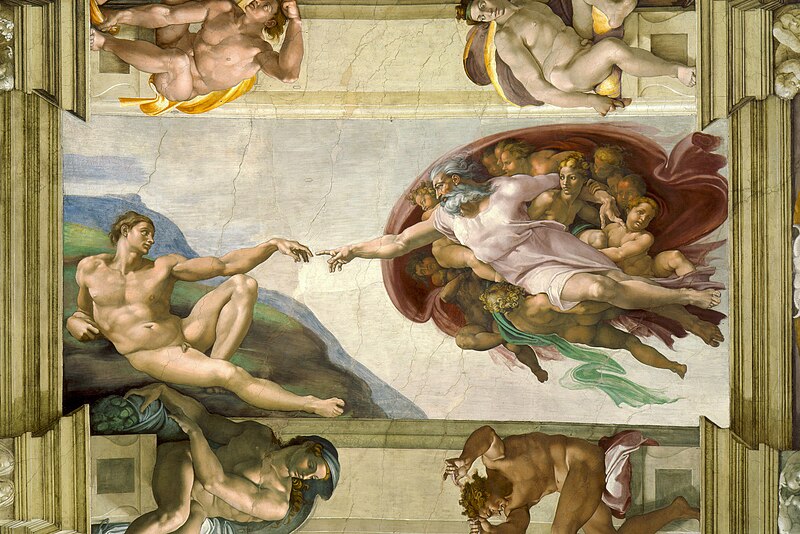

| Michelangelo, Creation of Adam, from the Sistine Chapel, c. 1511 |

Now we get a second account of the creation of humankind, which doesn't supplement the first version but rather complicates it. For "the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life." (Notice that it's not just "God" now, but "the LORD God." Looks like we've got a different voice telling the story.) This God plants "a garden eastward in Eden" for the man he has created, making it a place with "every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil." We're still vegetarians, it seems. (The "tree of life" seems to get forgotten in tellings of the story, and it's not real clear what its function is.)

The location of Eden gets a little more specific in the next few verses (10-14), as the narrator talks about the river that waters the garden and then divides into four more rivers: Pison, "which encompasseth the whole land of Havilah"; Gihon, which somewhat impossibly "compasseth the whole land of Ethiopia"; Hiddekel, "which goeth toward the east of Assyria" and is probably the Tigris, which borders Syria; and the Euphrates. Naturally, all attempts to trace any existing four rivers back to a single source are frustrating at best.

But back to this man in Eden, whom God commands not to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, "for in the day that thou eatest therof thou shalt surely die." (A rather pointless warning, since Adam -- as he begins to be called a couple of verses later -- can't have any concept of death until he learns about good and evil. God keeps throwing out Catch-22s like that.)

And now God decides the man needs "an help meet." But first he creates the animals -- which in the previous telling of the story he did before creating humans -- and parades them past Adam (so named for the first time) so that he can give them names. Again, naming things seems to be an essential activity. Then God puts Adam to sleep and takes out one of his ribs and fashions a woman out of it. So instead of "male and female he created them," we now get a primary creation, Adam, and a secondary one who "shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man." This last seems to be Adam's etymology. And the moral of is that, as Adam says, "This is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh," which leads to the corollary, "Therefore shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh."

Oh, and the narrator adds an aside: that "they were both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed."

Chapter 3

|

| Hans Baldung, Eve, Serpent, and Death, 1512 |

Eve doesn't stop to ask how the serpent knows this, just as the narrator here doesn't stop to explain what the serpent's motive for telling her the story is. She looks at the fruit and somehow sees "that the tree was good for food," and that it's pretty. And since it's "a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat."

Notice that there's no beating around the bush (as it were) here, no dialogue in which Adam says, hey wait a minute, Eve, we're not supposed to do that. She does it, and he does it, and that's that. And the first consequence of learning about good and evil? That it's bad to be naked. So they sew some fig leaves together and make aprons.

But God decides to take a stroll "in the garden in the cool of the day," and when he calls out for Adam, they hide. When they're discovered, Adam explains that he wasn't dressed for the encounter: "I heard thy voice in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself." Adam is not real bright, of course, and God asks the obvious question: "Who told thee thou wast naked?" But he doesn't pause for an answer. "Hast thou eaten of the tree, whereof I commanded thee that thou shouldest not eat?"

Notice how Adam sidesteps responsibility here: "The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat." He blames first Eve and then God, who gave her to him. Of course, Eve is no better at accepting responsibility: "The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat." The serpent doesn't get a chance to play the blame game before God curses him "above all cattle, and above every beast of the field," to go on his belly and eat dust. The children of Eve and their descendants will be the serpent's enemies, bruising his head, though the serpent will sometimes get his own back by bruising their heels.

Eve's punishment is the pain of childbirth, "and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee." Adam's is a lifetime of labor, no longer wandering around the garden and eating at leisure, but tilling the soil, pulling out weed, until he dies, "for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return." (There's an interesting tie here between the dust that the serpent eats and the dust that Adam becomes.)

Adam decides at this point to call his wife Eve "because she was the mother of all living." (So much for the inference from Chapter 1 that God created a number of human beings on that sixth day, but one still wonders where all the wives come from who participate in the begetting in the next few chapters.)

God makes them "coats of skins," putting an end to a vegetarian existence that would have pleased PETA, and says, "Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil." There's that "us" again, and this time it seems to refer to other beings with knowledge of good and evil. It's not just the royal Us. Now he mentions that "tree of life" again: He doesn't want the man (and presumably the woman) to "take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever." The tree of life wasn't prohibited before, but then it didn't have to be. Then God drives them out of the garden "and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life." Nobody, then, is getting at the tree of life.

But Cherubims? Where did they come from? There's a whole cast of superhuman beings that's just beginning to be glimpsed. Have they been there all along, before the "beginning"?

|

| Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden, 1427 |

| Titian, Cain and Abel, 1542-44 |

This makes Cain sulky, though God tries to talk him out of it: "If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him." Now, I admit to being a little puzzled by this myself: Who's ruling over whom? Cain over sin? Cain over Abel? There are some mixed signals here at best, though they don't quite explain why, after talking it over with Abel, Cain winds up killing him.

God comes to investigate, just as he did after Adam and Eve ate the fruit: Where's Abel? he asks Cain, who claims not to know: "Am I my brother's keeper?" But God won't put up with a smart-ass answer like that, for "the voice of thy brother's blood crieth unto me from the ground." Cain is cursed with bad crops: Because he spilled his brother's blood on the ground, "When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength." He'll become "a fugitive and a vagabond."

This is too much, Cain complains: No matter where I go, people will know what I've done and try to kill me. But God declares that if anyone kills Cain, "vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold," and he puts a mark on Cain to warn people of that. So Cain goes to the land of Nod, east of Eden, gets married -- uh, where did this wife come from? -- and fathers Enoch and builds a city that he names for his son.

Then follows the first of many series of begettings: Enoch begets Irad who begets Mehujael who begets Methusael who begets Lamech. Lamech has two wives: With Adah he begets Jabal, "the father of such as dwell in tents, and of such as have cattle," and, perhaps more interestingly, Jubal, "the father of all such as handle the harp and organ" -- the first musician. And with Zillah he begets Tubal-cain, "an instructer of every artificer in brass and iron," and his sister Naamah. Then Lamech does something very curious: He tells his wives that he has killed a man, and claims, "If Cain shall be avenged sevenfold, truly Lamech seventy and sevenfold." I'm not sure how he comes by that reasoning, but the Lamech murder case doesn't seem to have interested the narrator beyond this statement.

Meanwhile, Adam and Eve have another son named Seth, who fathers a son named Enos.

Chapter 5

Much begetting now, and a little backtracking, as the narrator, perhaps a different one, tells us again that Adam begat Seth who begat Enos. This time, we get a little chronology in the works: the ages of the patriarchs. Adam lived nine hundred and thirty years before he died. Sorry, nothing about how long Eve lived, but during that time Adam "begat sons and daughters," so she must have been around for a while. Seth lived to be nine hundred twelve, and Enos nine hundred five. They begat other sons and daughters, too, but it seems to be the firstborn that counts. Enos's firstborn was Cainan who begat Mahalalee, who begat Jared, who begat Enoch, all of them living up into at least the eight hundreds.

And here things get a little fuzzy. There was an Enoch before, remember? Cain's son. This Enoch is the father of the longest-lived of them all: Methuselah, who lived "nine hundred and sixty and nine years." But the funny thing about this Enoch is that we are told he lived only "three hundred and sixty and five years," a comparative stripling among patriarchs. Moreover, "Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him." Not that he died, but that he was taken. You can bet that there's been a lot of speculation about this.

But another funny thing: The Enoch who was "taken" has the same name as Cain's son, and that Enoch's great-grandson was named Methusael, which is a lot like Methuselah. And Methusael's son was named Lamech, the one who was involved in the funny murder, as befits a descendant of Cain. But Methuselah also begets a son named Lamech. So are we getting a confusion of genealogies here?

If the Lamech descended from Cain had some interesting offspring, the ancestors of musicians and metalworkers, so does this Lamech, who is supposedly descended from Seth. He begat Noah, who begat Shem, Ham, and Japheth.

Chapter 6

Things have gotten all muddled up in the begetting, and now they get muddled up in the telling. Men have begun "to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them." (Wouldn't be much multiplying without them.) As a consequence, "the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose." What's going on here? Who are these "sons of God"? Are they like other offspring of God, i.e., not men?

The next verse, unfortunately, doesn't clarify things:

Whose days? Mankind's? Is this God putting an end to those eight- and nine-hundred-year-olds? And what does this have to do with the sons of God wedding the daughters of men? And then we read "There were giants in the earth in those days," and that the offspring of the sons of God and the daughters of men "became mighty men which were of old, men of renown."And the LORD said, My spirit shall not always strive with man, for that he also is flesh: yet his days shall be an hundred and twenty years.

All of this seems to do with what happens next: God decides that humankind has grown so wicked that he is sorry he created it to start with: "I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man, and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them."

Still, there was Noah, "a just man and perfect in his generations, and Noah walked with God." We're also reminded of what we were told before: that Noah had "three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth." So he decides to save them, out of all the "corrupted" men on earth. He goes and tells Noah of his plans to destroy life on earth, and tells him to make "an ark of gopher wood," giving him the specs in cubits, with a window and a door and three stories inside. He's going to cause a flood, "and every thing that is in the earth shall die." But he will make a "covenant" with Noah and his wife and sons and his sons's wives.

They are to gather up two of every kind of creature on the earth, male and female, and food for them. So Noah does as he's told.

Chapter 7

|

| Edward Hicks, Noah's Ark, 1846 |

So Noah gets it done, and seven days later the rains start. It is "the six hundredth year of Noah's life, in the second month, the seventeenth day of the month," and it rains for forty days and forty nights, covering up "all the high hills, that were under the whole heaven." The waters rose up fifteen cubits (the ark itself is thirty cubits high) and covers the mountains. "All in whose nostrils was the breath of life, of all that was in the dry land, died." And the waters last for "an hundred and fifty days."

Chapter 8

|

| The Holkham Bible Picture Book, Noah Releasing a Dove and a Raven, c. 1320-30 |

So Noah, now in the first day of the first month of his six hundred and first year, takes the covering off the ark and sees dry land. On the twenty-seventh day of the second month, he sends his family and the animals out to repopulate the earth. He builds an altar and makes "burnt offerings" of "every clean beast, and of every clean fowl." (Imagine having spent all those months cooped up in this smelly boat, and then getting slaughtered for a sacrifice.) And "the LORD smelled a sweet savour" -- he does seem to have a thing for roast meat -- and promises never to do this sort of thing again. He promises it quite beautifully:

While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.

Chapter 9

|

| Giovanni Bellini, The Drunkenness of Noah, c. 1515 |

Retiring from the shipping business, Noah plants a vineyard. Unfortunately, he's a little too fond of the grape, "And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent." Ham sees his father naked, and goes and tells Shem and Japheth about it. They enter backward, not looking at Noah's nakedness, and cover him up.

When Noah sobers up and finds out that Ham had seen him naked, he curses Ham's son, Canaan, for some reason, making him a servant to Shem and Japheth. This "Hamitic" curse has been used as a justification for slavery: Notice that in Giovanni Bellini's painting, the son on the left, presumably Ham, is black.

Chapter 10

Since this is a new beginning for the human race, there are more begats. (One of Ham's grandsons is Nimrod, "a mighty hunter before the LORD.") Among them, the three sons of Noah create the new nations of the postdiluvian world.

No comments:

Post a Comment