Myth: The Collective Unconscious (C.G. Jung)

Myth: The Collective Unconscious (C.G. Jung)_____

C.G. Jung: The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

The most imaginative and influential of Freud's disciples (and, eventually in Jung's case, rivals), Jung posits not just an individual unconscious but a collective one, "which appears to us in dreams" and is "something like an unending stream or perhaps an ocean of images and figures which drift into conscousness in our dreams or in abnormal states of mind."

|

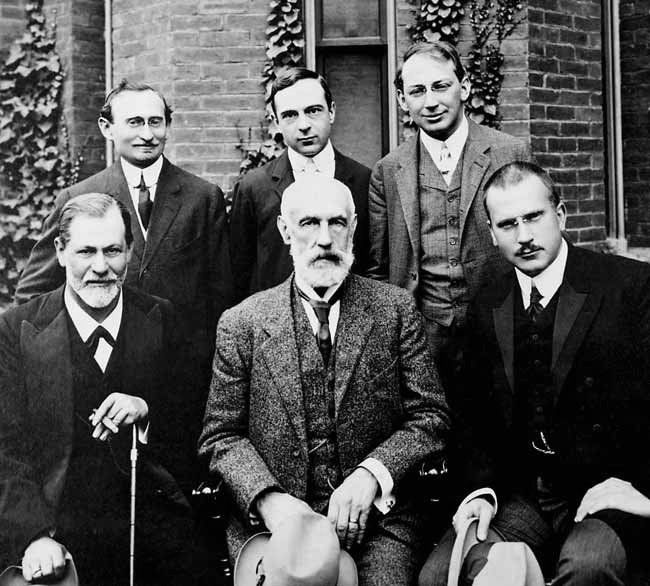

| C.G. Jung in 1910 |

The personal unconscious contains "the feeling-toned complexes" that "constitute the personal and private side of psychic life. The contents of the collective unconscious, on the other hand, are known as archetypes." The archetypes are intrinsically bound up with humankind's myths, which "are first and foremost psychic phenomena that reveal the nature of the soul."

Jung asserts that clinical work with patients reveals these recurring mythic patterns that "we can call 'motifs,' 'primordial images,' types or -- as I have named them -- archetypes." They manifest themselves in individuals as "unconscious processes whose existence and meaning can only be inferred, whereas the myth deals with traditional forms of incalculable age." The archetypes can be most clearly discerned in the religions of primitive man: "The primitive mentality does not invent myths, it experiences them." Like Malinowski, Jung rejects the idea that myths are created to "explain" natural phenomena, but he insists that they do indeed arise from what Malinowski dismissively calls "the dark pools of the sub-conscious, where at the bottom there lie the usual paraphernalia and symbols of psychoanalytic exegesis."Primitive man impresses us so strongly with his subjectivity that we should really have guessed long ago that myths refer to something psychic. His knowledge of nature is essentially the language and outer dress of an unconscious psychic process. But the very fact that this process is unconscious gives us the reason why man has thought of everything except the psyche in his attempts to explain myths. He simply didn't know that the psyche contains all the images that have ever given rise to myths, and that our unconscious is an acting and suffering subject with an inner drama which primitive man rediscovers, by means of analogy, in the processes of nature both great and small.

Not merely do they represent, they are the psychic life of the primitive tribe, which immediately falls to pieces and decays when it loses its mythological heritage, like a man who has lost his soul. A tribe's mythology is its living religion, whose loss is always and everywhere, even among the civilized, a moral catastrophe. But religion is a vital link with psychic processes independent of and beyond consciousness, in the dark hinterland of the psyche.The problem with discussing archetypes is that they can't be directly apprehended: "The ultimate core of meaning may be circumscribed, but not described, for "the pre-conscious structure of the psyche ... was already in existence when there was as yet no unity of personality (even today the primitive is not securely possessed of it)." Myths "give an approximate description of an unconscious core of meaning. The ultimate meaning of this nucleus was never conscious and never will be." It "expresses itself, first and foremost, in metaphors."

Because of this "perpetual vexation of the intellect," Jung says, "the scientific intellect is always inclined to put on airs of enlightenment in the hope of banishing" the mythic element. "Whether its endeavours were called euhemerism [the explanation that the gods arose from the actions of human heroes], or Christian apologetics, or Enlightenment in the narrow sense, or Positivism, there was always a myth hiding behind it, in new and disconcerting garb, which then, following the ancient and venerable pattern, gave itself out as ultimate truth." The scientific attitude, in other words, has its own archetypal roots: Consider, for example, the Prometheus myth in which the bringer of light, i.e., truth, is punished for hubris. "In reality we can never legitimately cut loose from our archetypal foundations unless we are prepared to pay the price of a neurosis, anymore than we can rid ourselves of our body and its organs without committing suicide." Jung here asserts the organic nature of the collective unconscious. If we fail "to connect the life of the past that still exists in us with the life of the present, ... a kind of rootless consciousness comes into being ... which succumbs helplessly to all manner of suggestions and, in practice, is susceptible to psychic epidemics." Jung probably has in mind here the political and ideological "epidemics" -- communism and fascism -- of the first half of the twentieth century.

The archetypes of the collective unconscious serve the same patterning function as "the axial system of a crystal, which, as it were, preforms the crystalline structure in the mother liquid, without having any material existence of its own." Freud's unconscious was a repository of instincts, and the archetypes "correspond in every way to the instincts," whose existence "can no more be proved than the existence of the archetypes."

C.G. Jung: The Psychological Function of Archetypes

In studying the unconscious we confront something very like Heisenberg's uncertainty principle:

Although the existence of an instinctual pattern in human biology is probable, it seems very difficult to prove the existence of distinct types empirically. For the organ with which we might apprehend them -- consciousness -- is not only itself a transformation of the original instinctual image, but also its transformer.But by indirections we can find directions out, and Jung asserts that he has done so through studying his patients, particularly the ones who express themselves through art. "And so it is with the hand that guides the crayon or brush, the foot that executes the dance step, with the eye and the ear, with the word and the thought: a dark impulse is the ultimate arbiter of the pattern, an unconscious a priori precipitates itself into plastic form." He has come to discover "that there are certain collective unconscious conditions which act as regulators and stimulators of creative fantasy activity and call forth corresponding formations by availing themselves of the existing conscious material." Dreams, too, "behave in exactly the same way as active imagination, only the support of conscious content is lacking."

Jung's critics find his conclusions unscientific, particularly when he says that "the archetypes have, when they appear, a distinctly numinous character which can only be described as 'spiritual,' if 'magical' is too strong a word. Consequently this phenomenon is of the utmost significance for the psychology of religion." Where the angels of science fear to tread. "The archetype is pure, unvitiated nature, and it is nature that causes man to utter words and perform actions whose meaning is unconscious to him, so unconscious that he no longer gives it a thought." But consciousness also "struggles in a regular panic against being swallowed up in the primitivity and unconsciousness of sheer instinctuality.... The closer one comes to the instinct world, the more violent is the urge to shy away from it and to rescue the light of consciousness from the murks of the sultry abyss."

C.G. Jung: The Principal Archetypes

The archetypes most clearly characterized from the empirical point of view are those which have the most frequent and the most disturbing influence on the ego. These are the shadow, the anima, and the animus.And so we begin with excerpts from 1951 and 1954. The first of these, the shadow, is like the photo negative of the personality, "a moral problem that challenges the whole ego personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort." (George Lucas, of course, made it into "the dark side of the Force," and look what a predicament that put Luke Skywalker into.) But awareness of the shadow "is an essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge, and it, therefore, as a rule meets with considerable resistance."

One way of coping with a recognition of the shadow is by projection, in which "the cause of the emotion appears to lie, beyond all possibility of doubt, in the other person. No matter how obvious it may be to the neutral observer that it is a matter of projections, there is little hope that the subject will perceive this himself."

But at least the shadow "is always of the same sex as the subject." If one is a man, one has to confront the anima; if a woman, the animus. They "are much further away from consciousness and in normal circumstances are seldom if ever recognized."

With a little self-criticism one can see through the shadow -- so far as it nature is personal. But when it appears as an archetype, one encounters the same difficulties as with anima and animus. In other words, it is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience for him to gaze into the face of absolute evil.And then there's the "mother imago." This is Jung's spin on the Oedipus complex, though without the killing-the-father part as an essential element. Like Freud, Jung's identification as male skews his psychological theorizing: that is, he takes maleness as normative, devoting most of his attention to it. The man wants "to touch reality, to embrace the earth and fructify the field of the world," but he also wants to return to the protective, nurturing state of childhood and infancy -- to his mother.

The mother ... has carefully inculcated into him the virtues of faithfulness, devotion, loyalty, so as to protect him from the moral disruption which is the risk of every life adventure. He has learned these lessons only too well, and remains true to his mother, perhaps causing her the deepest anxiety (when, in her honor, he turns out to be a homosexual, for example) and at the same time affords her an unconscious satisfaction of a mythological nature, for in the relationship now reigning between them, there is consummated the immemorial and most sacred archetype of the marriage of mother and son.Okay, to back up to that theory that homosexuality is a way of honoring his mother. It was tossed off almost as if it were common wisdom, which in his day it pretty much was. And thus Jung only compounded the problems of therapists, not to mention gay men. (And where do lesbians fit in?) But let's leave it at that and proceed.

Because of the dominance of the mother imago, "Every mother and every beloved is forced to become the carrier and embodiment of this omnipresent and ageless image which corresponds to the deepest reality in a man." In a word, he projects "this perilous image of Woman" onto the women in his life. "The projection-making factor is the anima, or rather the unconscious as represented by the anima.... She is not an invention of the conscious mind, but a spontaneous projections of the unconscious. Nor is she a substitute figure for the mother. On the contrary, there is every likelihood that the numinous qualities which make the mother imago so dangerously powerful stem from the collective archetype of the anima, which is incarnated anew in every male child."

The corresponding figure for women, the animus, Jung says, stems from the father as a figure of authority and order.

The animus corresponds to the paternal Logos just as the anima corresponds to the maternal Eros. It is far from my intention to give these two intuitive concepts too specific a definition. I use Eros and Logos merely as conceptual aids to describe the fact that woman's consciousness is characterized more by the connective quality of Eros than by the discrimination and cognition associated with Logos. In men, Eros, the function of relationship, is usually less developed than Logos. In women, on the other hand, Eros is an expression of their true nature, while their Logos is often only a regrettable accident.Like I said, for Jung, being male is normative. He goes on to explain that "in the same way that the anima gives relationship and relatedness to a man's consciousness, the animus gives woman's consciousness a capacity for reflection, deliberation, and self-knowledge." Anima and animus "represent functions which filter the contents of the collective unconscious through to the conscious mind."

Returning to the mother archetype, Jung provides some specifics:

To this category belongs the goddess, and especially the Mother of God, the Virgin, and Sophia. Mythology offers many variations of the mother archetype, as for instance the mother who reappears as the maiden in the myth of Demeter and Kore; or the mother who is also the beloved, as in the Cybele-Attis myth. Other symbols of the mother in a figurative sense appear in things representing the goal of our longing for redemption, such as Paradise, the Kingdom of God, the Heavenly Jerusalem. Many things arousing devotion or feelings of awe, as for instance the Church, university, city or country, Heaven, Earth, the woods, the sea or any still waters, matter even, the underworld and the moon, can be mother-symbols.Jung finds the archetype in concave and womb-shaped things, ranging from "the baptismal font" to "ovens and cooking vessels," and even "many animals, such as the cow, hare, and helpful animals in general." It's obvious that our reference to such things as "Freudian symbols" don't give Jung the credit he's due. He also adds some negatives to the list of mother archetypes, such as witches, dragons, graves, and mythical figures such as the goddesses of fate and Lilith. "There are three essential aspects of the mother: her cherishing and nourishing goodness, her orgiastic emotionality, and her Stygian depths." Jung even adds a reference in a footnote to Philip Wylie's once-famous attack on "momism" in Generation of Vipers. He isn't ready to condemn motherhood out of hand, but he observes:

I myself make it a rule to look first for the cause of infantile neuroses in the mother, as I know from experience that a child is much more likely to develop normally than neurotically, and that in the great majority of cases definite causes of disturbances can be found in the parents, especially in the mother.In the end, he says, "Our task is not ... to deny the archetype, but to dissolve the projections, in order to restore their content to the individual who has involuntarily lost them by projecting them outside himself."