Chapter 12: "Nenette"; Chapter 13: "Life Is a Gift"

The breakup with Beatrice Hastings left Modigliani in some danger: He had collapsed so often that he needed someone to look after him. His affair with Simone Thiroux was short-lasting, but at the end of 1916 he met Jeannette, or Jeanne, Hébuterne, an art student.

Jeanne's family was from the countryside near Meaux. Her parents had moved to Paris, where her father, Achille, was an executive with a perfume company. Her mother, Eudoxie, was interested in the arts, and had a romantic notion of the lives of artists. Otherwise she might not have given her daughter such a free rein in Montmartre. Jeanne's brother, André, was three years her senior and had begun his own career as an artist.

In May 1917, Jeanne and Modigliani began their affair. She was nineteen and he was thirty-two, but she had some skills he lacked: She was "able to manage a household, go on errands, and balance the budget, concealing, behind her self-effacing manner, a quiet dependability." She managed to keep their relationship a secret from her parents for a year. "Her mother finally guessed the truth in the spring of 1918 when Jeanne could no longer deny that she was pregnant."

Modigliani had been typically irresponsible in getting her pregnant. "His behavior was the height of recklessness as he went from one woman to another, exposing her to tuberculosis and also unprotected sex, that led all too often to the predictable results." He may have impregnated

Maud Abrantes, as well as both Beatrice Hastings and Simone Thiroux; the latter gave birth to a boy she named Serge, in May 1917. He denied paternity, "even though his friends saw a startling resemblance in the two-year-old Serge."

In July 1917, Modigliani and Jeanne moved into a two-room studio. "There was, of course, no kitchen, bathroom or toilet, running water, or central heat. But given the hovels he had inhabited this third-floor walk-up was almost luxurious." It was made possible in part by a change of art dealers, when Léopold Zborowski replaced Paul Guillaume. Modigliani negotiated a deal with Zborowski that included fifteen francs per day plus materials and models, as well as a studio in Zborowski's own apartment.

Zborowski wanted Modigliani to start painting nudes: "This made the best possible business sense. It was all very well to paint portraits, but if the subjects did not buy them the chances of encountering someone else who would were small.... Nudes were bound to make people stop and look." They are still among the best-known of Modigliani's paintings: In 2010 his

Nude Seated on a Sofa sold at Sotheby's in New York for $68.9 million, setting a record for a work by Modigliani sold at auction.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Nude Seated on a Sofa, 1917 (Source) |

|

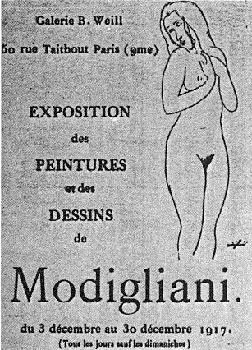

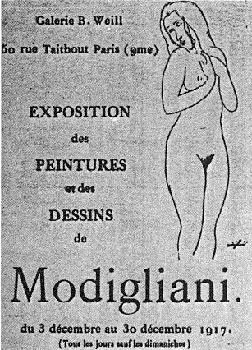

| Poster for Modigliani's first one-man show (Source) |

Zborowski was right in thinking that Modigliani's nudes would attract attention, and he was effective in making sure they got it. For the artist's first one-man show at the Galerie B. Weill in December 1917, there was a rather provocative poster, for which Jeanne Hébuterne was the model. Berthe Weill, the gallery owner, also placed several nudes in the window. The gallery was across the street from a police station, and the display attracted such crowds that a policeman asked Weill to remove the nudes from the window. When she refused she was hauled into the station, where the chief constable proclaimed the exhibition "an offense against public morals." Weill finally got the policeman to explain what was so offensive about the nudes: They had pubic hair.

The sensation the show caused did not, however, spur sales: only two drawings were sold, at thirty francs each. Weill, however, bought five paintings, if only to raise Modigliani's morale. He returned for a while to painting portraits, and when he went back to nudes he mostly used the conventional methods of concealment: drapery, or a strategically placed hand. "Five years later one of his forbidden nudes was sold at the Salle Drouout in Paris for twenty-two thousand francs."

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Nude With Necklace, 1917 (Source) |

Zborowski was successful in connecting Modigliani with several collectors, including Jones Netter and Roger Dutilleul. "Between 1918 and 1925, thirty-four of Modigliani's paintings and twenty-one of his drawings went through Dutilleul's hands." Zborowski suggested that Modigliani paint Dutilleul's portrait, but when Modigliani arrived for the sitting, Dutilleul recalled, "As he stood looking at my canvasses by Picasso and Braque, he was agonized. He said, 'I am ten years behind them,' and I had a lot of trouble convincing him this was not so." Dutilleul also recalled that he paid Zborowski five hundred francs for the painting, of which only one hundred went to Modigliani.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Roger Dutilleul, 1919 (Source) |

Meanwhile, Jeanne herself continued to paint, and in recent years her work has sold well. Two of her drawings, one a self-portrait and the other of Modigliani with a pipe, sold at Christie's in Paris in 2009 for more than $17,000.

|

| Jeanne Hébuterne, Self-portrait, date unknown (Source) |

|

| Jeanne Hébuterne, Modigliani With a Pipe, date unknown (Source) |

In March 1918 a new German offensive, including the shelling of the city by the giant cannon known as Big Bertha, as well as the outbreak of influenza that became a worldwide pandemic, caused many to leave Paris. According to Marco Restellini, it was Jones Netter who paid for Modigliani and Jeanne, among others, to leave the city for Nice and Cannes. They would be gone from Paris for a years. Modigliani's health continued to deteriorate and he came down with the flu that summer. He continued to paint, but not as often, though the quality of his work was high.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Léopold Zborowski, 1918 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne, 1918 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, A Zouave, 1918 (Source) |

The military threat to Paris ended, and by November the war was over. Meanwhile, Jeanne was about to give birth to their daughter. It seems that Jeanne and her mother remained in Nice, but it is not clear when Modigliani returned to Paris. The address on the baby's birth certificate is in Nice, and she was born at the end of November. But whether Modigliani was present for the birth is unknown, and the subject of many stories. He was, however, delighted with the child, who was named Jeanne. Her mother wasn't, however, and Modigliani himself took on the task of locating a suitable nurse for the child.

In May 1919, he was back in Paris, leaving Jeanne in Nice, and began working again in preparation for a show in London. In June, Jeanne sent Modigliani a telegram through Zborowski, asking for train fare to Paris. She was pregnant again, and in July Modigliani signed a note promising to marry Jeanne "as soon as the documents arrive" -- which presumably refers to some Italian citizenship papers.

The show in London, at the Mansard Gallery, was to be "the most important exhibition of French art in Lodon in almost a decade." It featured thirty-nine artists, including Dufy, Léger, Matisse, and Picasso, but Modigliani had more works than any of them in the show: fifty-nine pieces. The British critics had discovered him: He was praised by the influential Roger Fry, and the novelist Arnold Bennett, who had written the catalog for the exhibition, said, "I am determined to say that the four figure subjects of Modigliani seem to me to have a suspicious resemblance to masterpieces." Bennett bought a nude and a portrait of Lunia Czechowska, The show had been organized by Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, in collaboration with Zborowski, who offered them any picture from the exhibition at a bargain price. They chose one of Modigliani's identified as "

Peasant Girl," for which they paid four pounds at a time when the going price for one of his paintings was between thirty and a hundred pounds.

The painting

The Little Peasant caught the eye of the sixteen-year-old Kenneth Clark, who had been given a hundred pounds by his parents and told to buy a painting. He paid sixty pounds, but when he got home he realized that he could never hang it among his parents' "gilt-framed Barbizon paintings." So it was sold instead to the artist and collector Hugh Blaker, who eventually sold it to the Tate.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, The Little Peasant, 1918 (Source) |

Modigliani was too ill to travel to London for the exhibition. He had come down with another case of influenza. Paul Guillaume, who owned most of the paintings in the show, told Zborowski to put all sales on hold until Modigliani recovered -- he "knew the prices would double and triple if and when Modigliani died." This time, however, Modigliani didn't cooperate, but the end was only months away.

He thought that it was the influenza that made his health so poor that fall and winter, but it is likely that the tuberculosis had spread to his brain, leading to meningitis, the course of which is described as "going from headaches, general apathy, irritability, fever, and loss of appetite to delirium and coma." He was, however, exhilarated by the praise from London, and continued to work toward the Salon d'Automne, which would take place in November. But his behavior became more erratic, and when Marie Vassilieff met him on the street one day, she recalled, "I couldn't believe the change in him. He had lost his teeth; his hair was flat, straight; he had lost all beauty. 'I'm for it, Marie,' he said,"

One of his last subjects was Paulette Jourdain, a fourteen-year-old live-in maid at Zborowski's. She eventually became Zborowski's mistress and gave birth to his child, which Zborowski and his companion, Hanka, raised as their own. Paulette later became an art dealer, and collected Modigliani memorabilia.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paulette Jourdain, 1919 (Source) |

Another of his last models was Thora Klincköwstrom, a Swedish girl who came to Paris to study sculpture. On one of the sketches he made of her, he wrote a quotation from d'Annunzio:

La Vita e un Dono;

dai pochi ai molti:

di Coloro che Sanno e che hanno

a Coloro che non Sanno e non hanno.

Life is a gift from the few to the many, from those who know and have to those who don't know and don't have.

She recalled that while she posed for him, Modigliani coughed a lot and would occasionally stop for a drink of rum. Jeanne Hébuterne entered once during the sitting, and "Modigliani explained that Jeanne was expecting their second child and that their baby was staying with a nurse in the countryside outside Orléans."

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Thora Klincköwstrom, 1919 (Source) |

Although Modigliani told Thora that baby Jeanne was in Orléans, she seems to have been in the care of Lunia Czechowska for much of the time they were in Paris. Jeanne Hébuterne visited her daughter once a week. Sometime that fall Lunia decided to move to the south of France, and there are suggestions that Modigliani wanted to go with her. But Jeanne's pregnancy made her reluctant to travel or to be left alone in Paris. Marc Restellini thinks that there was much tension between Jeanne and Modigliani in the last months, and that he wanted the motherly attention that Lunia gave him. The late paintings of Jeanne are also unflattering.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne With Her Left Arm Behind Her Head, 1919 (Source) |

He also did only the second self-portrait that we know of:

His expression is indecipherable -- the art historian Sara Harrison likened it to a mask -- and his eyes are narrowed, their sockets blanked out with gray. The autumnal colors of fawns, ochres, and reddish browns, the grayish-blue scarf tied around his neck, provide the elegiac proof, if such were needed, that Modigliani knew how little time was left.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Self-portrait, 1919 (Source) |

Kenneth Silver notes that it is in the tilt of the head "that we strongly sense Modigliani's predilection for the Italian Renaissance and especially for the art of Botticelli, for whom the tilted head is a sign of spiritual buoyancy .... Italianate too ... are both the attenuated linear style and the idealization of the form, which is at the crux of Modigliani's art."

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, 1478 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, 1919 (Source) |

The last known photograph of Modigliani, taken in 191, shows eyes full of a painful awareness.... The received wisdom was that he drank himself to death. The reverse is the case; alcohol and drugs were the means by which he could somehow keep functioning, the necessary anesthetic, as well as hide the great secret that must be kept at all costs.

It is possible, Secrest says, that the secret of Modigliani's tuberculosis did get out in the final days, and that it provides "the most plausible explanation for what happened when he was dying and for days left alone." But even then, when a doctor was sent for, his illness was misdiagnosed as a kidney infection. Only when he lapsed into a coma was he finally taken to a hospital, where he died on January 24, 1920. He left an unfinished portrait on his easel, of the Greek composer Mario Varvogli, with whom he had gone out drinking on New Year's Eve.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Mario Varvogli, 1919 (Source) |

|

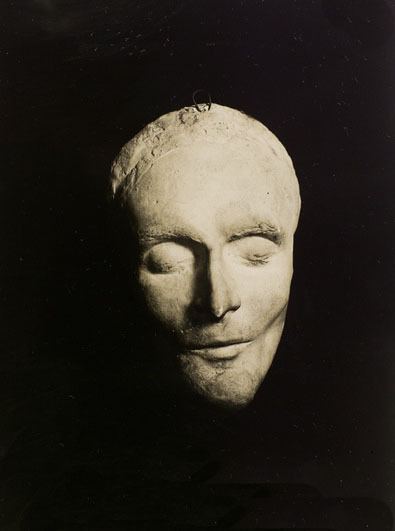

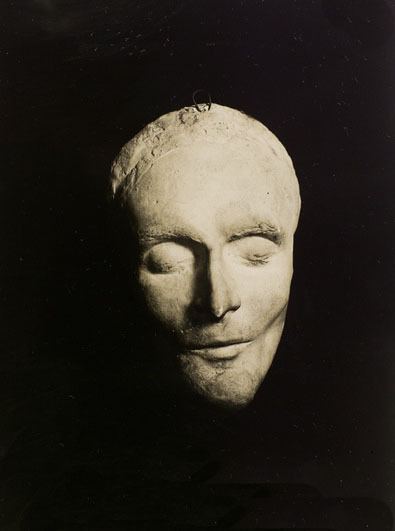

| Modigliani's death mask (Source) |

A death mask was taken, though it was somewhat botched because the plaster was not allowed to set long enough; Jacques Lipchitz was called in to restore it and make bronze castings. The sunken cheeks suggest both the emaciation and the loss of teeth that he suffered in the final year.

When the family was contacted, Emanuele sent word to spare no expense in the funeral, and that he would cover the expenses. The decision was made to bury Modigliani in Père Lachaise, the cemetery known for the famous artists who are interred there. The funeral procession attracted a crowd. "It is said that, as the numbers grew, speculators in art ran up and down the ranks, offering to buy for thousands of francs what no one would pay fifty for while he was alive."

No comments:

Post a Comment