Chapter 5: The Perfect Line; Chapter 6: La Vie de Bohème

As

a grown man, Modigliani was only five foot three, although this was

closer to the average height than it is today. He was involved in a

continuous succession of love affairs, apparently only with women,

although when he was a student he refused to join the others on their

visits to brothels. "Somewhat later, it is said, it was a point of pride

for Modigliani to talk about how many brothels he

had visited." He was also a bit of a dandy, especially while his uncle Amédée was paying the bills.

In

the spring of 1901, he and his mother returned to Livorno, but he then

persuaded his uncle to pay his expenses to study in Florence and then to

spend the winter in Rome. When he returned to Florence in early 1902,

he came down with scarlet fever, and after being nursed through the

illness by his mother, spent some time convalescing in the Austrian

Alps. In the spring of 1903, he went to study in Venice, where he became

acquainted with the painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni, as well as

the artists Fabio Mauroner, Mario Crepet, Cesare Mainella, Guido

Marussi, Ardengo Soffici, and Guido Cadarin.

|

Tino di Camaino, Carità, 1321 (Source)

|

It was the Chilean artist Manuel Ortiz de Zarate who filled him with the idea of going to the center of the art world, Paris.

Ortiz was not particularly impressed with Modigliani's painting at the

time, but that may have been because Modigliani wanted to become a

sculptor. Jeanne Modigliani, Amedeo's daughter, later wrote that her

father had been inspired to become a sculptor by his visits to churches

in Naples, and by the work of the fourteenth-century sculptor Tino di

Camaino in Siena and Florence. Modigliani went to the marble quarries in

Carrara, but gave up marble for the less expensive stone, producing

several sculpted heads before he decided to turn to painting again.

Fabio

Mauroner recalled that in Venice Modigliani "would spend the evenings,

and stay late into the night, in the remotest brothels where, he said,

he learned more than in any academy." In his work, Mauroner says,

Modigliani was looking to simplify the line, "which he saw as having a

spiritual value ... as a solution to his search for the essential

meaning of life. But while he was in Venice this ambition was hardly

more than a vague abstract idea in his mind." Others recall how in

conversation with Modigliani "a discussion of the practical problems of

technique and composition would take a sudden turn and start examining the riddle of existence."

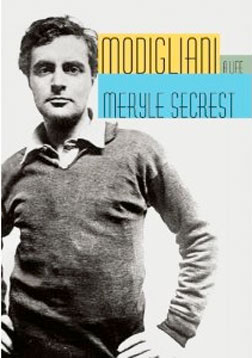

Early

in 1905, Amédée Garsin, Modigliani's benefactor, died, leaving him a

small inheritance that supported him for the next three years. In

January 1906, according to Jeanne Modigliani, he made the move to Paris,

arriving, Secrest says, "in style, as witnessed by numbers of his

friends, who thought he had been left a fortune by a rich uncle."

Others, however, claim that he didn't move to Paris until the fall of

that year.

The Paris Modigliani found during the Third Republic was a city in

dynamic flux, one of boundless opportunity.... As part of their

transforming revolution the Impressionist -- Manet, Monet, Caillebotte,

Cézanne, Degas, Morisot, Renoir, and Sisley -- brought a new sense of

daily life, real people in real situations. The year of Modigliani's

arrival Cézanne had just died -- of hypothermia, after being caught in a

storm at age sixty-seven -- painters like Bonnard and Vuillard were

developing their theories about flat planes of color, and an even more

radical group, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, and Rouault, had introduced

their own movement at the Salon d'Automne in 1905. Their resulting

canvases quickly earned them the name of "Les Fauves" -- "Wild Beasts."

Picasso and his Cubistic conundrums were just around the corner.

Modigliani enrolled in classes at the Académie Colarossi, where

Rodin, Whistler, and Gauguin had studied, as well as Ortiz de Zarate,

"who no doubt recommended it to Modigliani." Ludwig Meidner, a friend

from the time, remembered him "painting very small portraits on rough

canvas or smooth card with thin colors," some of which he "covered with

ten coats of varnish and, with their transparent golden appearance,

recalled the Old Masters." Some were put on display in a gallery in

December 1906, but none of them sold. Meidner remembered that Modigliani

was constantly drawing and that he developed his own technique:

"He drew from life on thin paper, but before it was finished he

placed another white sheet beneath it and a piece of graphite paper

between the two; then he traced the drawing, greatly simplifying the

lines.... Whereas in later years he developed his own style of painting,

his drawing remained essentially unchanged. Once he set to it, he could

produce dozens of portraits in this way."

Modigliani also made a friend of the artist Anselmo Bucci, who saw

the portraits in the gallery and sought him out. Bucci recalled

Modigliani claiming that the only good painter in Italy was Oscar

Ghiglia, and that he singled out Matisse and Picasso in France -- and

almost added himself. Meidner recalled that Modigliani was interested in

the works of Gauguin and Whistler, and that in addition to Matisse and

Picasso, "He also admired Ensor and Munch, who wee almost unknown in

Paris," as well as "some of the young Hungarian Expressionists who were

just coming into favor." Another friend, Gino Severini, wrote about

their discussions, "Impressionism no longer satisfied [us]; Picasso was

too much of an intellectual.... Modi never agreed with anyone. And in

particular, he didn't agree with Futurism. Futurism was based on color

relationships, on a certain impressionism. Modigliani didn't give a damn

about all that. He was interested in the Genovese primitivdes, in Negro

art, in the Venetians."

In the winter of 1906,

Modigliani moved into the center of the artists' quarter in Montmartre,

in what the poet Louis Latourette recalled as a "shanty ... in a state

of wild disorder." He also rented a studio that Meidner called "a

tumbledown shake on a treeless, ugly scrap of ground, and although it

was furnished in the most spartan manner, oppressive and neglected like a

beggar's hovel, one was always glad to go there for one found an

artistic atmosphere in which one was never bored."

But the center of the bohemian life was a café called the Lapin Agile.

|

Au Lapin Agile, 1880-1890 (Source: Wikipedia)

|

What was once a cottage on the north side

of Montmartre had become a tavern. It had been bought in 1903 by

Aristide Bruant, a cabaret singer for whom Toulouse-Lautrec had painted

several posters.

|

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, poster, 1892 (Source: Wikipedia)

|

Bruant had commissioned the artist André

Gill to come up with a sign for his café, and Gill produced a rabbit

with a wine bottle jumping out of a saucepan. It became known as "Gill's

rabbit" or the "

lapin à Gill," and hence, Lapin Agile. Bruant was a celebrity, and his place drew a crowd:

Along with the small-time criminals who had frequented Les

Assassins [the name of the club under its previous owner], there were

poets like Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob, writers like Francis

Carco and André Salmon, and, most of all, artists: Picasso, Braque,

Derain, Vlaminck, Valadon, Utrillo, Gris, and so many others. With his

usual perspicacity Modigliani at once attached himself to the list.

|

Secrest:

"Modigliani made himself a part of the new crowd with ease. He had the

rare gift of being perfectly delighted in any company. One sees this in a

series of candid camera photographs taken by Cocteau during World War

I.... Modigiliani is all eager attentiveness as Picasso explains a joke

to André Salmon to which, no doubt, he is about to add an irresistible

coda." (Image source)

|

Ilya Ehrenburg recalled Modigliani's "rare

combination of childlikeness and wisdom ... by childlikeness I mean

freshness of perception, immediacy, inner purity." Gino Severini said,

"Everyone loved Modigliani." He also began to dress like an artist, in

"a suit of chocolate-brown corduroy with a matching vest, an open-necked

shirt, and a red kerchief." His sense of style pleased Picasso, who

said, "There's only one man in Paris who knows how to dress and that is

Modigliani." Jean Cocteau called him "our aristocrat."

Almost everyone of artistic prominence, with the exception of

Matisse and Vlaminck, lived in Montmartre. Picasso, Juan Gris, and Kees

van Dongen resided in a former piano factory called the Bateau Lavoir, a

"squalid tenement" with rent that even an artist could afford, which is

why Modigliani eventually moved in too.

|

Picasso's

biographer John Richardson described the Bateau Lavoir as "so

jerry-built that the walls oozed moisture ... hence a prevailing smell

of mildew, cat piss and drains.... On a basement landing was the one and

only toilet, a dark and filthy hole with an unlockable door ... and

next to it, the one and only tap." (Image source)

|

The move seemed to have come in 1907, when Modigliani struck up a conversation with André Utter, an amateur painter who was working on a picture on a street in Montmartre. Modigliani said he had just returned from London and couldn't pay the bill at the hotel he was staying at. The proprietor had confiscated his paintings until he paid up. Modigliani was never penniless, because he received money from his mother and from his brother Emanuele, but Secrest comments that he had "the Garsin predilection for taking advantage of good times and drowning in debut in lean ones."

He could also rely on the generosity of Rosalie Tobia, who had once been a nude model but was now "completely shapeless." She ran a small restaurant, Chez Rosalie, and was sympathetic to starving artists. Modigliani was one of her special favorites, though they also had frequent fights over his inability to pay the bills. He sometimes paid her in drawings, as did other artists. "The legend, probably true, is that she kept them, covered with grease, in a kitchen cupboard, the rats gnawed away at them, and when she thought of cashing them in it was too late." On her walls were paintings by Modigliani, Picasso, and Utrillo, and Modigliani once painted a fresco on one of her walls that she disliked and had it whitewashed over.

Modigliani was also "thinking of giving up painting and going back to sculpture." He would "court the masons working on new buildings over a bottle of wine and then make off with a block of stone." But he was not yet ready to give up painting. In 1907 he exhibited seven works at the Salon d'Automne, but sold none of them. The same exhibition also featured forty-eight paintings by Cézanne, who had died the year before, and Modigliani was dazzled by them. He carried in his pocket a reproduction of one of Cézanne's several paintings of a boy in a red vest. In the same year, he saw the pioneering Cubist painting

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in Picasso's studio, a work that even Picasso's contemporaries failed to appreciate at first sight. "Modigliani admired Picasso without reservation. 'How great he is,' he once remarked. 'He's always ten years ahead of the rest of us.'"

|

| Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 (Source) |

Although his paintings were not selling, in 1907 Modigliani met one of the first collectors of his work, Dr Paul Alexandre, who had moved into a twelve-room house that the city was planning to demolish. Alexandre persuaded the city to give him a lease on it and made it into a place for artists to meet. Modigliani began visiting there in November 1907, and after finding a studio space nearby was a frequent visitor.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paul Alexandre, 1909 (Source) |

On his first visit to Alexandre, he was accompanied by an American woman, Maud Abrantes, about whom little is known, except that he "made several studies of her and painted her portrait in grayed-off pastels.

|

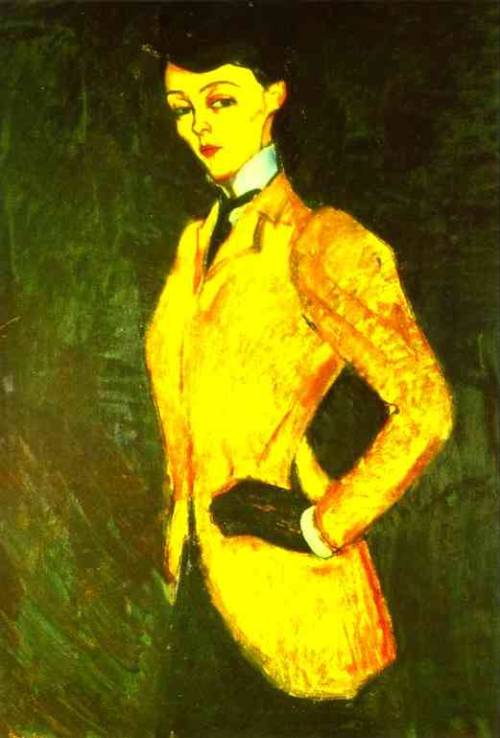

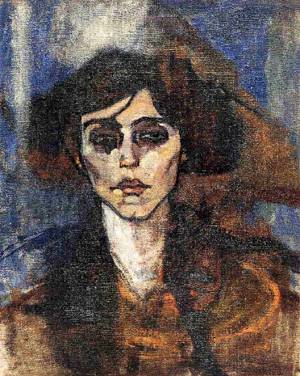

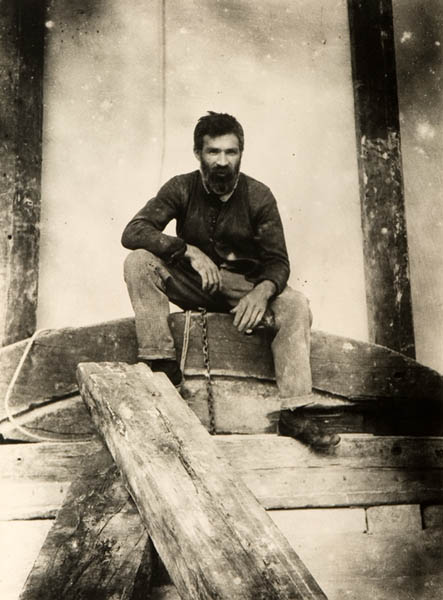

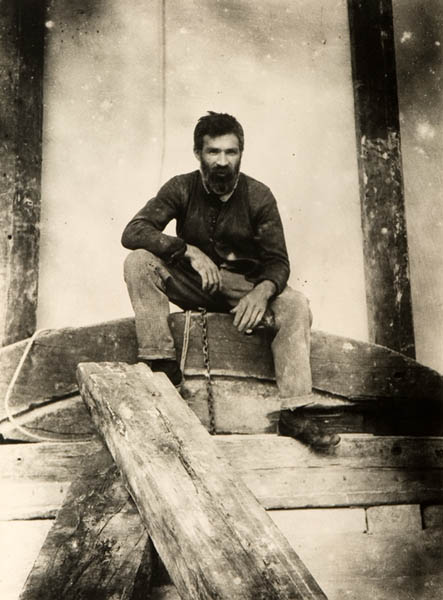

| Secrest: "Her features, well marked and handsome, are notable for the eyes, which are disproportionately large, and smudged with blotches of paint as if to indicate mute suffering." (Image source) |

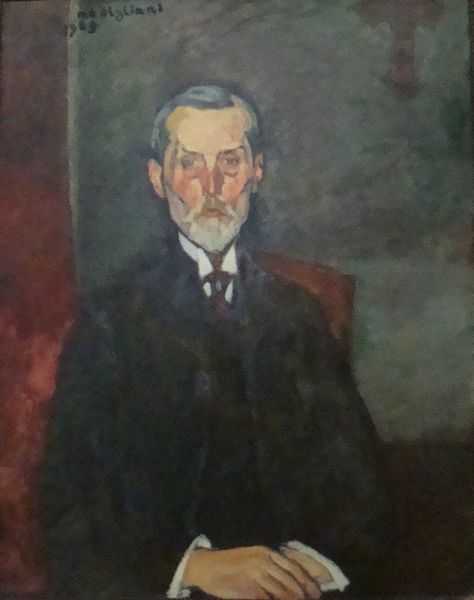

One of Alexandre's first commissions to Modigliani was a portrait of his father, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre.

|

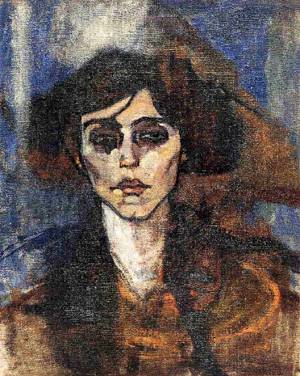

| Secrest: "The old man confronts the viewer with grave distinction, his white beard precisely trimmed to reveal a pink bottom lip, his eyes tired but calm. He has a natural authority and so does his son, who strikingly resembles him." (Image source) |

Paul Alexandre was impressed by Modigliani, and in him the artist "had found someone with an eighteenth-century concept of the patron who recognizes, and nurtures, a rara avis. He was twenty-six; Modigliani was twenty-three." Alexandre was struck by Modigliani's perfectionism, and by the way he would make countless sketches of a subject until he found the precise line he wanted. "Anything less than perfection would be tossed on the floor. This is where Alexandre made, perhaps, his ultimate gift to posterity: he picked them up."

There was much drinking and drug-taking at the Alexandre salon, but many witnesses assert that Modigliani did not drink excessively, and although he participated in the experimentation with drugs, especially hashish, he "seldom drew while taking hashish, preferring to recall his visions in sobriety with the aim of reproducing the heightened effect."

|

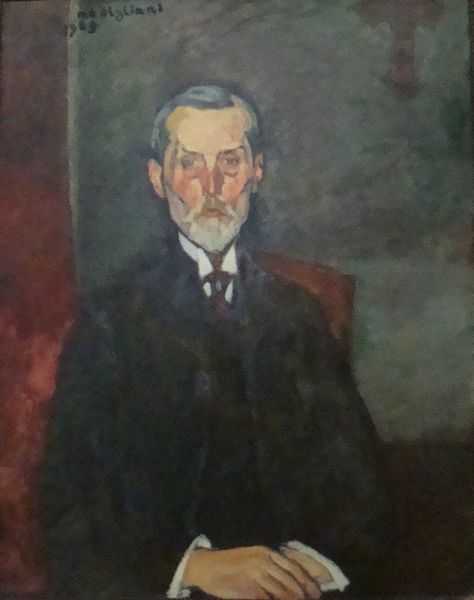

| Constantin Brancusi, 1905 (Source) |

Alexandre also acted as a patron to Constantin Brancusi, who would become a friend of Modigliani's.

[Herbert Read wrote,] "Brancusi strove to find the irreducible organic form, the shape that signified the subject's mode of being, its essential reality." Searching for the reality behind appearances: this, in Modigliani's case, was wedded to his belief in art as a magical force offering the path to exorcism and transfiguration.

Modigliani had become the prototypical bohemian, careless with money, given to reckless behavior, but enduring despite the sometimes self-imposed hardships. For "the belief that art was still a noble cause, in stark contrast to the grubby, money-focused goals of the bourgeoisie, when to the heart of the Bohemian creed.... It did not seem to matter to Modigliani that he was hounded by debts, sleeping on the run, with no money for good and no buyers for his drawings. He was surviving somehow."