Margaret Atwood is maybe the only famous writer with whom I have been personally acquainted. And that was a long time ago, when we were graduate students at Harvard and her then-to-be-and-now-ex-husband was one of my roommates. She wasn't famous then, except in Canada, where one of her books of poetry had won the Governor General's Award, but we were sure she would be. She was tough-minded and more than a little bit intimidating to a Southern boy like me, who was then unused to women who took no shit from men. I've had this book since I received it as a review copy some years ago, but haven't got around to reading it until now. (I didn't review it, because I have a policy of not reviewing books by people I know -- or even used to know. You can get into a lot of trouble that way.)

Lost Illusions, by Honoré de Balzac

Translated by Herbert J. Hunt

Penguin Classics, 1971

Reading Proust has made me more acutely aware of my gaps in French literature, to which he's constantly alluding: I've read some Flaubert and Stendhal, some Victor Hugo, recently a novel by Zola, but only one novel by Balzac. I've had this paperback for a while. Herbert J. Hunt's translation, which was first published in 1971, is exceptional, not so much because of accuracy -- to which I can't speak -- but because of its extraordinary readability. It has the feel of an early 19th century novel, which of course it is, though some translators believe that everything must be turned into a more contemporary idiom. The chief deficiency of the edition is the comparative lack of footnotes to clue the reader into Balzac's allusions to French history and social customs. A little more ongoing explanation of the financial and legal terms used in the novel would be welcome too -- the plot hinges on debtors and creditors, and although Balzac devotes some chapters to explaining the legal and financial background, his explanations need some explaining. Still, this is the kind of novel in which you feel the pulse of the characters -- they become alive to you. And although the ending, especially where Lucien is concerned, feels more like a moral fable -- the poet who sells his soul to the devil -- than a novel, and like a segue into other novels in the Comédie humaine, it satisfactorily rounds things off for most of the characters. And you sure do learn a lot about printing and paper-making (not to mention social-climbing) in early 19th-century France.

The Infinities, by John Banville

The Infinities, by John BanvilleKnopf, 2010

I was intrigued by the premise of the book: that the Greek gods are still around and intervening in even the mundane affairs of humans, and by the glowing blurbs from British reviewers (the book appeared first in Britain). I haven't read any Banville before, though I'm aware that he won the Booker Prize for The Sea. The text quoted from in my blog is from the bound galley I was sent for review.

I really wanted to like this book more than I did. It is clever, witty, imaginative and filled with ideas -- all things I prize in a book. And yet it lacks coherence, perhaps even a sense of full commitment by the author to his novel. I don't feel Banville's dedication to the material, a sense that he really had to tell this story.

It is a kind of homage to the story of Amphytrion -- the mortal cuckolded by Zeus, who took Amphitryon's own shape to seduce his wife, Alcmene -- and to Kleist's play based on the story. And there is something theatrical about the setting -- an isolated country house where a family has gathered to wait for the death of the father, comatose after a stroke. The place is also haunted by the Greek gods -- Hermes keeps watch on things while his own father, Zeus, has his way with the beautiful actress wife (named, rather obviously, Helen) of the son of the dying man. Both son and father are named Adam, which only adds another layer of confusion to the story, which is narrated by Hermes, and then by the elder Adam in his comatose state, and then by both of them, blending and alternating until it's not clear who, other than Banville, is telling the story.

The elder Adam is a prominent intellectual -- a mathematician or a philosopher or a theoretical physicist -- whose ideas about infinity, or rather infinities, have changed the world: applications of his theories have led to automobiles that run on seawater. But the world in which the novel takes place is not our own: In this alternate world, for example, Mary, Queen of Scots, beheaded Elizabeth I, not the other way around. And Alfred Russel Wallace, not Darwin, was credited with the theory of evolution, which in any case has been disproved.

Yes, Banville is having fun, playing as much with Shakespeare (there is a character whose name, Wagstaff, is a translation of "Shakespeare") as with the classic myth or Kleist's version of it. Another character, Benny

Grace, is both the god Pan and a version of Shakespeare's Puck, and the whole thing has a Midsummer Night's Dream quality to it. But the novel has a dark side, too: Old Adam's first wife drowned herself; his current wife, Ursula, is an alcoholic; their daughter, Petra, is a morbid young woman who is compiling a list of human ailments and secretly mutilates herself.

Is the problem with the novel that there is too much going on and not enough of it winds up anywhere meaningful? Perhaps. It is a verbal feast -- Banville is often compared to such word wizards as Nabokov and Joyce -- but I came away from it feeling a little queasy, as if I'd just been to a banquet of appetizers.

Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, by Jonathan Bate

Random House, 2010

A few years ago, I set myself the task of reading all of Shakespeare's plays, and I guess I'm about to make a cycle through them again. But first, this intriguing biography showed up, and while I've read my share of Shakespeare bios, this one seems a little different in the sense that it purports to be a kind of intellectual history as well.

I think it's the best biographical approach to Shakespeare that I've seen. Many things are unknowable about Shakespeare's life, including his relationship to his wife and the period between their marriage and his showing up in London as an actor-playwright. That hasn't stopped writers from speculating, however, and from going to the plays and poems to plug the biographical holes. Even the best conventional biography of Shakespeare I've read, Stephen Greenblatt's bestselling Will in the World, relies on that approach more than Bate does.

What Bate gives us is, as his subtitle indicates, "a biography of the mind," an investigation of the culture and the intellectual climate in which Shakespeare lived and moved and had his being. What could he have known as a man born in sixteenth century England who lived into the start of the seventeenth, and, more important, what did he do with what he knew?

The result is not a typical linear cradle-to-the-grave biography, which may frustrate some readers who want chronology above all else. Bate structures the narrative on the "seven ages of man" speech delivered by Jacques in As You Like It: infant, schoolboy, lover, soldier, justice, pantaloon, and oblivion. But given that there's not much documentable fact about some of these "ages" -- it would be hard to get many pages out of Shakespeare's infancy other than when, where, and to whom he was born -- and there's no evidence that Shakespeare was ever a soldier or a judge, Bate uses these periods in Jacques's speech to explore the intersection between Shakespeare's life and the works that touch on the several periods.

Thus, "infancy" deals with the place where Shakespeare was born and grew up, Stratford-upon-Avon and the Warwickshire countryside, and the ways in which it is reflected in the work, as well as the ways in which this provincial background is played off against the cosmopolitan London where he became famous. It acknowledges that the year of his birth, 1564, was a plague year, and that plague shaped his career, periodically closing the theaters and forcing the actor-playwright to find other means to express himself and earn his livelihood.

At the same time, Bate uses what he discovers about the places, events, and ideas that Shakespeare encountered to illuminate the works. He uses the Renaissance humanism of writers such as Montaigne and Erasmus to examine The Tempest in ways that I found transformed my own reading of the play. He contrasts Shakespeare's financial success with that of his contemporaries to suggest that practical common sense was for him a prevalent virtue, one that informs his attitudes toward the characters he created.

Without taking sides in the controversy over whether the marriage of Will and Anne was a happy one, he examines the complexities of male-female relationships in the plays. On the other hand, he examines the sonnets not so much for what they might tell us about Shakespeare's sex life, gay or straight, but as the poet's treatment of a popular genre and as a reflection on the era's prevailing attitudes toward love.

He shows how the fall of the earl of Essex sent a shockwave through the political and literary establishment and may have shaped Shakespeare's later career. He examines Elizabethan geopolitics -- the relationship between the parts of the world dominated by Spain and the parts that were England's potential allies -- and the way it is reflected in plays such as Othello and The Winter's Tale. He shows how England's internal politics form the subtext not only of the history plays but also those set in past eras (King Lear) and in ancient Rome.

He looks at the theater itself -- the way it was run, the actors with whom he performed and for whom he wrote -- and how it shaped what he wrote. He questions whether Shakespeare ever really retired from the theater before his death, challenging the idea that Prospero's renunciation speech at the end of The Tempest is really the playwright's own valedictory to the stage.

And he tackles the most challenging question of all: What did Shakespeare really believe? He looks at the ten instances in which the word "philosopher" appears in the plays, and concludes that Shakespeare privileged experience over dogma, likening him in this respect to Erasmus and Montaigne. And he comes to the quite satisfactory conclusion that, of all the characters in Shakespeare, for all the attempts to find the "real" Shakespeare in Hamlet or Prospero or Prince Hal, the one who comes closest is Enobarbus in Antony and Cleopatra:

"Enobarbus embodies the pliable self recommended by Epicurus and Montaigne.... Intelligent, funny, at once companionable and guardedly isolated, full of understanding and admiration for women but most comfortable among men (there is a homoerotic frisson to his bond with Menas and his rivalry with Agrippa), clinically analytical in his assessment of others but full of sorrow and shame when his reason overrides his loyalty and leads him to desert his friend and master, Enobarbus might just be the closest Shakespeare came to a portrait of his own mind."

Zuleika Dobson, by Max Beerbohm

Modern Library, 1938

My copy of Zuleika Dobson was given to me by a fellow graduate student on the occasion of our graduation. I haven't read it since then. In 1998 a panel commissioned by the Modern Library called it one of the 100 best novels of the 20th century -- No. 59 to be exact. Whether it's a better novel than The Moviegoer (60), The Catcher in the Rye (64), The House of Mirth (69), or The Adventures of Augie March (81), I can't say.

In truth, I think it misleading to call Zuleika Dobson a novel. It has less in common with the books mentioned above, more or less conventionally realistic novels, than with books like Gulliver's Travels or Lewis Carroll's Alice books -- works of fiction that step out of the confines of conventional narrative realism to pursue other aims, such as satire or whimsy. Zuleika Dobson is both: a whimsical satire. It's also a parody of romantic fiction, an ironic tribute to Oxford University, and a metafictional commentary on the nature of the novel itself.

Unlike the novels above, in fact unlike almost all of the other 99 novels on the list (Finnegans Wake the chief possible other exception), it is not character-driven. Zuleika and the Duke of Dorset don't propel the plot so much as they are propelled through it by the whim of the author -- or, if you wish, the gods who preside over their destinies. It is a cheerfully callous book, though not a cold-hearted one. Beerbohm has some obvious affection for his creations, or he wouldn't spend so much time with them, sorting out their various reactions to each other.

The entire book is premised on an ironic refutation of Rosalind's assertion that "men have died from time to time and worms have eaten them, but not for love." Ironic, because the absurdity of the mass suicide of the entire Oxford student body over love for Zuleika is manifest. But Beerbohm's irony gives the romantic fantasy its due. Like Zuleika and her grandfather, Beerbohm is rather tickled by the whole notion -- again not coldly or callously, but out of a kind of amused respect for the foolish nobility of the act.

It's well, however, to note the date of the book: It was published in 1911. Three years later, the young men of England would begin dying heroically and absurdly in places like the Somme. Beerbohm's book would take on the aspect of chilling prophecy, especially in light of the Duke's comparison of the suicidal fervor of his fellow undergraduates to the jingoism that inspired Britons before the Boer War.

The book is also clear-sighted in its treatment of both Oxford nostalgia and ivory-tower detachment from the real world, as in the Junta's meticulous devotion to its rituals and the dons' studious avoidance of the truth about what has happened before the "bump-dinner," despite the undergraduates' absence from the Hall. If there is one passage that sums up Beerbohm's attitude toward the university, it is this:

Oxford, that lotus-land, saps the will-power, the power of action. But, in doing so, it clarifies the mind, makes larger the vision, gives, above all, that playful and caressing suavity of manner which comes of a conviction that nothing matters, except ideas, and that not even ideas are worth dying for, inasmuch as the ghosts of them slain seem worthy of yet more piously elaborate homage than can be given to them in their heyday.

It still seems strange to me to call Zuleika Dobson a novel, but if it is one, it's a novel of ideas.

The Adventures of Augie March, by Saul Bellow

The Adventures of Augie March, by Saul Bellow (Novels 1944-1953)

The Library of America, 2003

It was Martin Amis, I think, who called this the great American novel. That in itself makes me feel like I should read it again after [coughs] years.

(Novels 1944-1953)

The Library of America, 2003

I've read this novel twice before: once, many years ago, and then again a couple of years ago when I was recovering from my brain infection. On the second reading, I didn't recognize it as the book I had remembered. So considering that I wasn't in full possession of my faculties that time, I thought it was worth another run-through. The edition also contains The Victim and Adventures of Augie March.

Henderson the Rain King, by Saul Bellow

Henderson the Rain King, by Saul BellowPan Books Ltd, 1959

On the first page of this yellowing paperback, I have written

Charles MatthewsWhich tells me that it has been nearly fifty years since I bought this book, an English paperback edition, in a bookstore in Tübingen, where I spent a year as a Fulbright scholar. And nearly fifty years since I read it in a seminar taught in English by a professor from UMass-Amherst, Jules Chametzky. (We had to have proof of having attended one course at the university in Tübingen to fulfill the requirement for the Fulbright. I took the easy way out.) So I think it's time to read it again.

Tübingen

Burgsteige 18/XV

Philip Roth calls Henderson "a stunt of a book, but a sincere stunt -- a screwball book, but not without great screwball authority." I couldn't agree more. Bellow's stunt is, among other things, to take the African adventure tale, particularly the hairy-chested version of it associated with Ernest Hemingway or popular writers of the '50s like the now-forgotten Robert Ruark, and turn it upside down. Not that Bellow is lampooning Hemingway, but rather that he's taking the whole self-discovery aspect of Hemingway to its philosophical, post-WWII extreme. Bellow's Africa is an imaginary place, populated by sages and seers who aid the protagonist in his quest for ... well, what? Even Henderson doesn't really know what he's looking for, though it has something to do with "bursting the spirit's sleep" and with the voice inside him that persists in nagging, I want, I want, I want. Bellow has anticipated the whole New Age self-improvement era, with its various gurus and cults.

It's also a supremely American book. I note at one point in my running commentary on the book that it reminds me, especially in Henderson's voice, of Mark Twain. Henderson is a late-middle-age Huck Finn who lights out for the territories -- only there are no more territories in America, so he has to go to Africa. He carries with him the presumptuousness of Americans proud of their know-how, leading to disaster when his attempts to rid a village of its plague of frogs destroys their water supply. But he also has the American's susceptibility to the exotic, and the willingness to believe that enlightenment can come from the primitive.

So at the end, is Henderson a pig or a lion? Or perhaps he's just a forlorn tamed bear -- the avatar that Bellow audaciously presents to us in the novel's final pages. Bellow wisely doesn't say.

Herzog, by Saul Bellow

Penguin Books, 2003

Because one good Bellow deserves another. I've never read this one, but I filched a stack of Penguin paperbacks, including several by Bellow, when I left the Mercury News.

Considering that it's a novel with nothing you could call a plot, Herzog is an inexhaustible book. It touches on elemental human relationships (sexual, familial, social) and spins off into lofty philosophical debates, reflections on civilization, on the meaning of death, and on the American experience. It tempts a reader into close analysis while at the same time mocking such analysis. Moses Herzog is at once the most meticulously observed of characters and the most impossible to grasp as a whole.

It's a third-person narrative whose voice is clearly that of the person whose story is being told. The device isn't used for a coy ironic distancing, as in The Education of Henry Adams, but rather it grows out of the kind of fractured consciousness that is Herzog's. He feels his plight -- the cuckolded husband, the -- and feels it deeply, but at the same time he wants to observe it from the outside, to watch himself in the act of being "a loving but bad father" to his children, "an ungrateful child" to his parents, "affectionate but remote" to his siblings. "With his friends, an egotist. With love, lazy. With brightness, dull. With power, passive. With his own soul, evasive." He is, in short, a character in a novel that he is writing about himself.

Or, perhaps more appropriately, a letter he is writing to himself. One way of approaching Herzog is to treat it as an epistolary novel, in which Herzog, whose current intellectual pastime is to write letters to other people, is also writing this very long letter to himself about how he has wound up where he is. Which brings up a key problem: How do we know that Herzog is being honest with us -- or with himself? How do we know that his ex-wife, Madeleine, is the conniving shrew that he presents to us? Or that Valentine Gersbach is the oily opportunist that Herzog thinks him to be?

The truth is, we don't. Other people in the novel seem less perturbed by Herzog's plight, by Madeleine's and Gersbach's actions, than he is. This includes Gersbach's wife, Phoebe, who claims that Valentine and Madeleine are not having an affair. Is Herzog self-deluded? Everyone thinks he's crazy, and he has come to accept the fact that he might be. He is certainly unstable. His career is in a shambles, and two failed marriages have left him so wary of women that he can't trust his own instincts when it comes to his latest amour, Ramona, who seems to accept him for what he is. And when he finally starts to take some sort of action, it's utterly foolish and self-destructive. He is saved from its potentially disastrous consequences by his own ineptness.

Which is only to say that Herzog is like Leopold Bloom, a kind of Everyman. Like Bloom, he is a misfit who desperately wants to fit, a cuckold, a wanderer, a dreamer, and Herzog, like Ulysses, ends on a note that is positive enough to provoke hope, but also ambiguous enough to allow that hope to be dashed. Like the narrator of In Search of Lost Time, he is an intellectual with the potential to liberate himself from the past while at the same time so aware of his past that he becomes inextricably tied to it.

More Die of Heartbreak, by Saul Bellow

Penguin Books, 2004

The next in my Bellow Cycle.

This is a hard novel to get into. There is the usual Bellovian intellectual overload to be got through, and the eccentricities of the characters are something of a barrier. And then there's the feeling that maybe we've seen Bellow explore the male incomprehension of women once too often. But once you're into it, and have worked out the various relationships and conflicts, it's a rewarding novel not least because it is often very funny.

It's a novel about a man and his uncle. I don't recall having seen that central relationship in a novel before -- except maybe Tristram Shandy. Kenneth Trachtenberg is the son Benn Crader never had, and Benn is the father Kenneth perhaps wishes he had had. But there is something a smidge homoerotic about their closeness, too. Since this is Bellow we're talking about, both are intellectuals: Benn is a famous botanist whose only truly passionate relationship is with plants. Kenneth is a junior academic specializing in Russian studies. Benn is a widower remarrying after years of the solitary life; Kenneth has a daughter by a woman who won't marry him. And much of the novel deals with the very peculiar relationships that each has with women who seem to fling themselves at these very odd men.

The central plot deals with Benn's relationship with his younger, beautiful second wife, Matilda, who seems to have married him primarily for his celebrity -- she envisions herself presiding over a salon -- but also because there is a chance that he can become a millionaire. That involves winning over a shady politician who also happens to Benn's uncle -- there are layers of avuncularity in the novel -- and who may have cheated Benn and his sister (Kenneth's mother) out of a fortune.

Everybody in the novel wants something -- Kenneth wants to marry the mother of his daughter -- except Benn, who just wants to be left alone with his plants. And in the course of working things out, Bellow gives us reflections on sex, on death, on marriage, on botany, on being Jewish, on Europe and America, on academia, on law and politics and on the movie Psycho.

Penguin Clasics, 2004

Once more unto the Bellow Cycle, this time with a novel published in 1970. It is in some ways a book of its age, when anxiety over the state of America was at a peak: student protests, the Vietnam war, racial tensions, political assassinations, urban decline all seemed to give the times an apocalyptic character. Set against all that was the impending exploration of the moon. So Bellow comments on the Zeitgeist through the eyes of a man who has survived another apocalypse: the Holocaust. Artur Sammler has seen the worst that can be thrown at a human being, and it gives him a certain detachment from the madness around him.

Mr. Sammler's Planet contains a thread of plot -- Sammler's dealings with the dysfunctional Gruner family on whom his livelihood depends, and with his own dysfunctional daughter, Shula, who "borrows" a valuable manuscript in the delusion that it will aid her father in a project that he is not actually engaged in: a memoir of his association with H.G. Wells. What plot there is is near-farce, bracketed by Sammler's encounter with a black pickpocket on a New York City bus. But as so often in Bellow's novel, the plot is swathed in pages of reflections on the nature of history, philosophical speculation and social commentary, as well as Sammler's own memories of how he survived the Holocaust in Poland. At least this time we are spared the midlife crises of a Henderson or a Herzog or a Kenneth Trachtenberg: Sammler is beyond midlife and lacks the usual Bellovian preoccupation with what women want.

Somehow Bellow makes his peculiar combination of elements work, but the ending is so unsettlingly unresolved that the novel feels a bit like a shaggy-dog story. Sammler's final words, "we know, we know, we know," seem like an echo of Henderson's "I want, I want, I want," in that they serve as a kind of ironic mantra, a means of escaping the fact that we don't really know at all, just as what Henderson wants is never really clear to him or to us.

Genesis: The Bible

Oxford University Press

Well, why not? It's the fount of Western literature. What I propose to do here is a somewhat naive reading of the King James Version, followed by a bit of research into some of the commentaries on the Bible.

The Passage, by Justin Cronin

The Passage, by Justin CroninBallantine, 2010

I don't read a lot of bestsellers anymore. I had to, when I was a book section editor, but now I'm surrounded by shelves of books I haven't read and should, or books I've read but don't remember. But when I heard about this novel, it sounded like my kind of book. What that says about me, I leave it to you to surmise.

I can imagine the pitch to the publishers and then to the movie producers: The Hot Zone meets True Blood. And in truth that's what attracted me to it. The idea that vampirism might be a medical condition, even if it's a far-fetched concept, has a lot of appeal to me. If Cronin had stuck more closely to that premise I might have liked the book more, but then it got all muddled up with telepathic communications that don't seem to have much to do with the virus: the whole business of Sister Lacey and her psychic connection with first Amy and then Doyle, for example. I'm willing to admit that a virus might even allow a human being to grow a carapace, to alter its musculature and make it superstrong, maybe even to glow. But the parapsychology is a bit hard to swallow, especially when it's demonstrated by people who aren't even infected.

Still, I'm game for a good yarn, so I stuck with it. And I'll probably be first in line for the sequel, if only because there are so damn many loose ends that I want to see if Cronin ties up. (For example, what about Hastings/Zero, who was infected with the virus in its natural state in Bolivia? Did he become the same kind of Queen Bee that Babcock became? He seems not to have a connection with the Twelve.)

On the whole it's a strong book for what it is: a deft handling of genre conventions, with more than a touch of Tolkien (Peter as Frodo, the virals as orcs). It's more cinematic than literary, but who am I to knock that?

The Privileges, by Jonathan Dee

The Privileges, by Jonathan DeeRandom House, 2010

I've been blurbed enough with quotations taken out of the context of my reviews that I know not to put complete faith in blurbs. But when the review copy of this book arrived with blurbs from writers I like, such as Richard Ford ("verbally brilliant, intellectually astute, and intricately knowing") and Jonathan Franzen ("a cunning, seductive novel about the people we thought we'd all agreed to hate"), then I really have to give it a go.

Dee's novel is an exploration -- and sometimes a refutation -- of some familiar propositions:

Tolstoy: "Happy families are all alike."

Fitzgerald (allegedly): "The rich are different."

Hemingway (allegedly): "Yes, they have more money."

Faulkner: "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

Conventional wisdom: "Money can't buy happiness."

Traditionally, a writer who wants to put his characters to the test deprives them of everything: Think of Job on his dung heap, Lear on the heath. Dee does the opposite: He gives them everything. He creates the perfect couple, Adam (the first man) and Cynthia (the goddess of the moon, which, though its light is reflected, has power over the tides -- in this case the tides of wealth created by her husband). He gives them perfect children, though they are challenged, as their names indicate: April (the cruelest month) and Jonas (whose near-namesake is, like Job, one of God's guinea pigs).

Novels are driven by tension, and it's hard to generate tension if your central characters are perfect: a loving, faithful couple who do everything to provide their children with a happy life. Of course, Adam and Cynthia Morey aren't perfect: He's a workaholic who flirts with the law by starting an insider-trading scheme; she's unfulfilled by the life of a stay-at-home mom. So for part of the novel, the tension comes from uncertainty about whether Adam will get caught and Cynthia will have a breakdown. And once that tension is resolved, there's the tension about what will happen with their overprivileged children: Will April turn into a Paris Hilton or a Lindsay Lohan? Will Jonas have the resources to find the authenticity he finds lacking in the life of the fabulously and famously wealthy?

No, happy families aren't exactly all alike, and the rich aren't different just because they have more money. But the novel also points out the truth in those axioms. More to the point is Faulkner's aphorism. For Adam and Cynthia both believe that they can unplug themselves from the past, and near the novel's end, Adam proclaims to Cynthia, "you and I pretty much had to start over in terms of family, and we did it. We succeeded. We're Year Zero." And she agrees: "Baby, we didn't just succeed, we're a fucking multinational.... We've trademarked ourselves."

But the affirmation of their rootlessness, which comes ironically when Cynthia is at the deathbed of the handsome, feckless father she has barely known, ignores the plight of their children. As a girl, April made up a family history for a class that encouraged self-esteem, and as a young woman she is terrified by the emptiness that faces her when she contemplates her future. Jonas has sought, first in music and then in art, for something genuine that he finds lacking in contemporary culture, and his quest for it puts his life in the kind of jeopardy that a privileged existence hasn't prepared him for.

As Franzen's blurb says, these are "the people we thought we'd all agreed to hate," and Dee audaciously presents them in the context of a love story. Jonas says of his parents, "They are just really in love with each other, in this kind of epic way." Dee even inverts the paradigm of the love story: His begins with the wedding that conventional love stories end with. The rich are supposed to be the targets of Tom Wolfean larger-than-life satire. Dee's novel is not without satire, but his rich family is as much the weapon of delivery as the target.

Daily, Before Your Eyes, by Margaret-Love Denman

Michigan State University Press, 2005

Margaret-Love Denman and I go way back. Like way back to the first grade at Oxford Elementary School in Oxford, Mississippi, and on through high school and college till our paths departed. She was kind enough to send me a copy of this, her second novel, about three years ago. I've been meaning to read it since then but, well, you know. No excuses. Now is the time.

Because we do go way back, however, and because I "know the landscape," as she said in the inscription in my copy, the blog entries for this book are a little more personal than usual. But bear with me -- it's my blog after all. This is a novel worth reading and she's a writer worth knowing. (Try her first novel, A Scrambling After Circumstance, too.)

American Notes, by Charles Dickens

Modern Library, 1996

Since I seem to have a Bellow cycle and a Shakespeare cycle going, why not a Dickens cycle? I think I've read all of the Dickens novels (though I have no memory of Barnaby Rudge or The Mystery of Edwin Drood) but I've never read American Notes.

Ignore the critical distaste in Christopher Hitchens's introduction, which seems designed to discourage reading the book. Although there is some justice in the criticisms, the book is as revelatory about Dickens as it is about the United States. He is a stranger in a strange land -- one he didn't create, as he created Dickensian England -- and he can never forget it. But he rarely makes criticisms that are based solely on snobbish conviction of the superiority of England. He sees what the Americans are trying to do, and sometimes he disagrees with it. But he recognizes that they are touchy and proud and that this makes it sometimes difficult to establish rapport with them.

Barnaby Rudge, by Charles Dickens

Penguin Classics, 1997

I think I've read this novel before, but I have no memory of it. It's one of Dickens's two historical novels -- the other being A Tale of Two Cities -- and it's not widely read, partly because it doesn't have one of those great signature Dickens characters, like Micawber or Miss Havisham.

It's easy to see why Barnaby Rudge is one of Dickens's less popular novels. It's overlong and overplotted, and it's awkwardly structured, falling too neatly into two halves. The first half centers on the frustrated love of Joe Willet for Dolly Varden, and the equally but differently frustrated love of Edward Chester and Emma Haredale, and on the murder of Emma's father. The second half focuses on the anti-Catholic Gordon riots of 1780. The two halves are knit together by the effects of the riots on the Willets, Vardens, Chesters and Haredales, and on the title character, the "idiot" Barnaby. But the characters -- especially Joe, Edward and Emma -- are such feeble stock figures, such conventionally drawn vessels of virtue, that it's hard to get emotionally involved with their fates. Moreover, even the "Dickensian" grotesques, such as Sim Tappertit (a name that elicits snickers from 12-year-old boys of all ages and sexes) and Miggs, are only fitfully amusing, and they quickly wear out their welcome.

The one almost successful character in the novel is Hugh, the mysterious thug who may be the closest thing Dickens ever came to a tragic figure. He enters the novel as an enigmatic and almost attractive figure -- a wild man of sorts -- and descends into villainy during the riots. But at the end, he attains a kind of tragic awareness, which he expresses in his speech before he goes to the gallows.

Dolly Varden, who became the novel's most popular character, even to the extent of causing a fashion craze later in the nineteenth century, is one of Dickens's better ingenues -- which is, to be sure, not saying much, since the Dickensian ingenue is typified by the saintly Agnes of David Copperfield. But by using Dolly's flighty mother and the jealous Miggs as foils, Dickens gives her some substance, allowing her to make foolish mistakes while enhancing her attractiveness.

The treatment of the riots shows Dickens's gift for the sensational, culminating in the orgiastic revel at the vintner's house, when the mob immolates itself in a fiery, drunken stupor, a fatal bacchanal of sorts. But the vividness of the riot scenes contrasts too sharply with the insipidity of the novel's lovers, who settle down at the book's end into a complacent rural fertility, producing hordes of cherubic little Joes and Dollys.

The chief flaw of the novel, however, is Barnaby himself, who resembles no mentally challenged person ever encountered in this world. He is a vehicle for pathos, a holy fool who goes astray, but he grows so annoying in this role that it's hard to care whether he's rescued from the gallows. And if you don't care about that, it's hard to care about anything that Dickens wants you to care about. Still, the novel is distinguished by Dickens's passion for justice and his contempt for hypocrisy. At its best moments, they give it a spine of conviction that keeps it from collapsing into a welter of melodrama.

For American readers, the oddest thing about the novel may be its time frame: The action takes place between 1775 and 1780, when the American War for Independence was taking place. Yet the only reference to this conflict, which surely must have preoccupied Britons even more than the Gordon riots, is in Joe's loss of an arm at the siege of Savannah, which takes place offstage from the novel's main action -- and in the chronicles of the Revolutionary War is for many people almost a footnote. Was Dickens, who was preparing for his trip to America while the novel was appearing, afraid of alienating American readers by bringing that conflict to the fore in his narrative?

Penguin Classics, 1996

The first time I read Bleak House I was all at sea. The novel seemed a vast jumble of characters and incidents. And then I reached the "spontaneous combustion" chapter and I recognized that I was in the hands of a master.

That sense of mastery continued on this reading, for who can deny that the Dickensian imagination was a powerful and mysterious force, when it can sustain a 900-plus-page novel that an attentive reader never wants to put down? Or that literature would be poorer if it lacked Mr Turveydrop, Mrs Jellyby, Mr Bucket, Mrs Pardiggle, Smallweed, Skimpole, Guppy, Miss Flite, Krook and the rest?

But there is a serious flaw at the heart of Bleak House, and it's the divided narration. I will in fact defend Esther Summerson: She comes closer to being a convincingly real-world character than almost any other of Dickens's women, partly because Dickens has held true to his concept of her as a slave to duty, that cardinal Victorian virtue, but has shown that even dutifulness has its downside. Esther nearly forgoes a fulfilling relationship with Woodcourt because of her sense of duty to Jarndyce (not to mention her habitual self-deprecation, which as Dickens suggests was instilled in her by a harshly religious upbringing). But adopting Esther's point of view for much of the novel only draws attention to the artificiality of narration, and prevents him from bringing either irony or poignancy to Esther's dilemma with regard to her pledge to Jarndyce and her attraction to Woodcourt.

Dickens was no intellectual, and he sometimes embarrasses himself when he ventures into the world of ideas, as he does in his scathing portraits of social ideologues, falling into the ridicule of feminism characteristic of his time. He visits the sins of the mothers unto the third generation by making Caddy Jellyby's daughter a deaf-mute, and his true conservatism reveals itself when he can't bring himself to imagine that Charley Neckett might break from her class and actually learn grammar. His squeamishness about sex means that his most virile characters, like George Rouncewell, are condemned to celibacy (or, as queer theorists might propose, a furtive relationship with Phil Squod), while Lady Dedlock must hound herself to the grave (literally) out of guilt, and it can only be hinted that Ada is pregnant.

But for all its author's muddle of attitudes, Bleak House stands firmly as an imaginative construct, as an exhaustive working-out of its author's sentiments and preoccupations. If it tells us more about its author than its author tells us about his characters, that's not necessarily a flaw.

Homer & Langley, by E.L. Doctorow

Random House Paperback, 2010

I've read some Doctorow before: Ragtime, Billy Bathgate, The Book of Daniel. I appreciate what he's up to: the exploration of 20th-century American history through fiction. This paperback was sent to me as a review copy.

Doctorow has taken a true story, that of a pair of eccentric recluses who lived in accumulating disorder, and fictionalized it effectively. He extends the lifespan of the real Collyer brothers, who died in 1947, into the 1970s, and tinkers with other details, such as the birth order of the brothers (Homer was in fact the elder) and the onset of Homer's blindness, which happened much later in his life. The story is told from Homer's point of view, evoking the other legendary blind Homer.

The novel is strongest in its characterization of the brothers, making Homer the sensitive observant one who, because of his blindness, is dependent on the more damaged and sometimes paranoid Langley for a view of the world. And Doctorow's decision to extend the brothers' lifespan makes it possible for the novel to serve as a critique of American history, from World War I (in which Langley is gassed) through Prohibition and the gangster milieu, into the Depression and World War II, through the anticommunist 1950s and into the hippie era of the 1960s and finally into the urban decline of the 1970s.

But there are times when the prowling through history seems facile and tendentious. Far better are the parts of the novel when Doctorow just lets Homer and Langley be themselves. Then the novel is often warm and funny, or sad and infuriating, as the circumstances demand. And the end is heartbreaking.

The Modern Tradition: Backgrounds of Modern Literature, edited by Richard Ellmann and Charles Feidelson Jr.

Oxford, 1965

I actually used this anthology as a textbook in an honors freshman English class I taught way back when. Remembering it as a splendid source of all sorts of ideas about literature and art, I wanted to return to it to refresh my memories of what it contains.

I had forgotten the philosophical density of many of the entries, and often found myself in deeper intellectual waters than I'm accustomed to: Kant, Hegel, Marx, Schopenhauer, Whitehead, Dewey, William James, Croce, Nietzsche, Bergson, Kierkegaard, Barth, Tillich. I floundered, but never sank.

And I found a solution to a problem that has been bothering me: If we're postmodern, what is it that we're post?

To be modern is to have experienced the death of God. And not only that, to have gone through some if not all of the Kübler-Ross "stages of grief": denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Few moderns, of course, stay long in denial -- that's the place for the fundamentalists of the religious right today. But many of them are angry about it, and blame the Enlightenment and rationalists, or materialists, or scientists for killing off God. And they turn to bargaining, trying to replace divinity with the imagination, or with historical process, or with evolution toward an Übermensch.

Depression seems to lead to existentialist resignation. And acceptance opens the gate to the postmodern acceptance of plurality, of diversity, of subjectivity, and the rejection of metaphysics.

Or as Samuel Beckett put it: "I can't go on, I'll go on."

The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, by Richard Holmes

The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, by Richard Holmes Pantheon, 2008

One book leads to another. When I finished Being Shelley, I took this one down from the shelf and added it to my to-be-read stack. And when I read Mason & Dixon I was all the more convinced that I should read it. Both of those books are rooted in the material covered by Holmes's: the scientific discoveries of the later eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Half a century ago, the physicist and novelist C.P. Snow stirred up talk with an essay called "The Two Cultures," in which he lamented the ignorance of "literary intellectuals" with regard to science. He claimed that when he asked literati to state the second law of thermodynamics, he was met with blank stares and hostility. "Yet I was asking something which is about the scientific equivalent of: 'Have you read a work of Shakespeare's?'" I suppose it's owing to Snow's little dig that I know the second law is the one about entropy, though if you asked me to explain it further I'd be at a loss.

The point is that Holmes's book revived my awareness of that old gap -- though how significant the gap really is may still be open to question. I happen to know an awful lot about Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats. But if you had asked me a couple of weeks ago about their contemporaries, Joseph Banks, William Herschel, and Humphry Davy, I would have drawn blanks. Especially about Banks, but even though I must have read the footnote to Keats's "On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer" that explains the poem's allusion to Herschel's discovery of the planet Uranus, I probably wouldn't have thought about it. As for Davy, the only thing that would have come to mind was the old clerihew: "Sir Humphry Davy / Abominated gravy." And even then I wouldn't have come up with the next two lines: "He lived in the odium / Of having discovered sodium."

I may not have crossed Snow's culture gap yet, but Holmes's fine book has helped me start building the bridge. It's surprisingly readable, perhaps because Holmes lards it with anecdotes. Perhaps too many anecdotes: I still don't know the point of putting so much emphasis on Davy's relationship to the "maid of Illyria," Josephine Dettela. There's an imbalance between the forays into the private lives of Banks, Herschel, Davy et al. and the explanation of the significance of their works. And I'm still not entirely clear on what the phrase "Romantic science" is supposed to mean. But I much appreciated Holmes's efforts to tie the work of the scientists (a word, incidentally, that wasn't coined until 1833, another gee-whiz nugget from this book) to the work of the poets. And some of the selections from Davy's own poems are quite impressive.

Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel

Henry Holt, 2009

I wanted to read this book when it won the Man Booker, but then I want to read a lot of books that win a lot of prizes. And a lot that don't. What put it at the top of my list was watching "The Tudors" -- history as soap opera. It seemed the right time to flesh out my knowledge of the era with something a little more literary. And I had read and reviewed Mantel's memoir, Giving Up the Ghost, and figured here was a writer to keep an eye on. I was right.

In fact, watching "The Tudors" was helpful, my sixteenth-century English history not being as fresh as it might be. Wolf Hall is a nice corrective to that series, however, for the Thomas Cromwell of the novel is a far more complex and engaging figure than the lean, lurking one portrayed by James Frain in the series. And a far more sympathetic one than the Cromwell of Robert Bolt's play and screenplay, A Man for All Seasons.

The Cromwell vs. More conflict, while less central to the novel than to Bolt's play, does serve to establish Cromwell as a key figure in the development of what might be called the modern man. Mantel's Cromwell, a self-made man, is constantly bristling at the references to his low birth, but the pragmatic approach he has taken not only to surviving but also to rising in society has made him aware of the way the world is changing. More's idealism is played off against Cromwell's Machiavellianism, but we come to recognize that Cromwell's view of the world is really our own.

Some online critics -- on Amazon and at Goodreads -- have complained of Mantel's "pronoun abuse," that it's difficult sometimes to determine which "he" is speaking. It's a somewhat tricky device, though usually "he" is Cromwell. But I think in the end it's an effective way of keeping the point of view Cromwell's without resorting to either the over-intimate first person or the more distancing tactic of labeling the "he" as "Cromwell" every time. And testing a reader's attention is also a useful trick to keep one focused on the dialogue and what's being said and implied.

Edited by Frank Romany and Robert Lindsey

Penguin Classics, 2003

I've read Doctor Faustus, Tamburlaine, The Jew of Malta and Edward the Second before -- I'm sure. I must have done so in grad school, not for any course but in preparation for comps and orals. And I have some sense of them from excerpts and allusions in other books. But this is as good a time as any to brush up my Marlowe.

The temptation, of course, is to compare Marlowe to Shakespeare, or to wonder whether Marlowe might have challenged Shakespeare's supremacy if he had lived long enough to mature as a playwright (and perhaps to be influenced by Shakespeare's success). Certainly his extant plays, with the possible exception of Doctor Faustus, exhibit none of the mastery of characterization or the variety of language -- or even the theatrical skills of dialogue and plotting -- that even the early plays of Shakespeare show.

Dido, Queen of Carthage is a sometimes lovely, often silly pageant whose best parts are derived from Virgil. Tamburlaine is a lot of bluster with no real depth of character and an absence of any real plot development: people come in, boast, challenge Tamburlaine, and are defeated. Then Tamburlaine gets sick and dies. The Jew of Malta begins to show some glimmers of characterization and of wit -- Barabas is comic in his villainy, and he does receive some degree of justification for his actions, even though the play remains disgustingly anti-Semitic at its roots. There again, we have the example of Shakespeare, who while partaking of the era's anti-Semitism, made Shylock a convincingly real figure -- enough so that the play can still be performed without leaving too much of a sour taste in the audience's mouth.

Faustus is his most enduring, most accessible work, largely because its central theme, that of intellectual overreaching, still has some resonance for us. And both Faustus and Mephistopheles are "playable" -- the kind of roles that actors can find some meat and nuance in. Edward the Second comes close to being a good play, though it's much too long and disjointed -- structure is not one of Marlowe's strengths. And who knows about The Massacre of Paris? The text is confusing in its chopping-up of time and in the inconsistency of its characterization, particularly of Anjou/Henry III, but it's possible to see how it might have been a better play than Edward the Second, largely because there are some real issues -- religion and power -- at its core, whereas Edward lacks sufficient evocation of a backstory -- why, exactly, is everyone so upset about Gaveston anyway?

A Game of Thrones: Book One of A Song of Ice and Fire, by George R.R. Martin

Bantam Books, 2011

This was an impulse buy in the supermarket. But I liked the HBO series and was curious to see if it held up as a novel. The fantasy genre is not one of my favorites, though I love Tokien -- at least The Hobbit and LOTR -- and this seemed from the TV series to have a nice hard edge to it, and not a lot of self-conscious funny names. (Lannister and Stark are surely meant to echo Lancaster and York, right?)

Count this as a pleasant surprise. Martin knows how to create varied and interesting characters, how to tell a story that engages the reader, and best of all, how to evoke an entire imaginary world without making it sound "made up." He manipulates point of view with skill, telling his story through characters who give us a faceted vision of events: the cynical Tyrion, the naive but brave Jon Snow, the spoiled romantic Sansa, the innocent but damaged small boy Bran, the fiercely maternal Catelyn, the tragically heroic Eddard, the resilient and resourceful Arya, and the initially malleable but finally determined Daenerys.

What makes it all work, I think, is that the story so clearly resonates with the histories and myths of our own world. It's not just that the names are only slightly exoticized versions of common English names -- and the Dothraki so clearly evoke the ancient antagonists of the West, from the Mongol hordes to the Arab conquerors -- but that the conflicts are those of the chivalric era: family dynasties, struggles for the throne, fear of the unknown and the magical. And the internal conflicts -- love vs. honor, passion vs. duty -- are those of the traditional sagas. Even the deep backstory is resonant: the doomed "children of the forest" are the doomed indigenous people of all countries: Celts, American Indians, Australian Aborigines, and so on.

Fortunately, Martin also finds the right tone and diction for the story. There are a few lapses into cliché and into high-minded preachiness, but fewer than you might expect. And once or twice there is a joke too contemporary for the context, as when Tyrion says to his father about the mountain clansmen he has inveigled into following him: "They followed me home. Can I keep them?" Even then, the laugh it gets almost excuses the ease with which it is gotten.

It has to be said that for once, reading the source of a movie or TV adaptation makes you admire the skill of the adaptation. It was faithfully done.

A Clash of Kings, by George R.R. Martin

Bantam Books, 2011

So, no help from HBO this time -- though of course, many of the characters linger in my mind from their TV embodiments. The second book is more heavy on magic than the first, but the strength of the series remains its human element: skillful characterization and fine manipulation of point of view. I admit to getting a little bogged down in military strategy and tactics, never my strong suit. And the elaborate fantasy of the city of Qarth, particularly Daenerys's journey through the warlocks' palace, occasionally struck me as erring on the silly side. Melisandre is a little too much like a Disney villainess, though I doubt Disney would ever have come up with anything so startling and scary as the scene in which she gives birth to a killer shadow.

For a book whose plotting is an endless series of cliffhangers and whose narrative is chopped up into eight distinct points of view, it's a remarkably coherent novel. Or part of a novel.

A Storm of Swords, by George R.R. Martin

Bantam Books, 2011

So many cliffhangers to be unhung. And so many new ones to be created. This is an almost exhausting, though sometimes exhilarating read. And it has a couple of moments that took me completely by surprise, one of which actually made me gasp out loud. You never know whom Martin is going to kill off next.

A Feast for Crows, by George R.R. Martin

Bantam Books, 2011

I guess I shouldn't be surprised that a lot of readers were disappointed in this volume in the series. After all, they had waited years to hear more about what happened to Tyrion and Daenerys and Jon Snow, and instead find themselves reading about the power struggle for the throne held by Balon Greyjoy and conflicts in the ruling house of Dorne. I'd be kind of pissed off too. But the thing you have to remember about Martin's opus is that it's not just an epic fantasy, it's also a political novel, an intense and many-faceted account of the truth behind Lord Acton's familiar dictum: "Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely."

I can also see the justice in the objection that Martin has made Cersei a two-dimensional character: a fairytale evil queen, like the ones in Disney movies. But Cersei's wickedness has its other side: an almost comical stupidity, a blindness to her own motivations, an indifference to all consequences except the immediate one of proving her superiority to her father. I could wish she were more Lady Macbeth than Maleficent, but she's entertaining to watch anyway.

A Dance With Dragons, by George R.R. Martin

Bantam Books, 2011

Now I can share in the frustration of readers waiting for Martin to deliver, to relieve our suspense about the fates of Jon Stark and Daenerys Targaryen, to wonder if Arya will ever get out of that damned temple and Sam will become a maester, and so on.

Silk Parachute, by John McPhee

Silk Parachute, by John McPheeFarrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010

When I was a magazine editor, I always held up McPhee as a model for my writers: Find a subject that hasn't been overdone, I would say, then research the hell out of it and write about it beautifully. Easier said than done, of course. McPhee is the master of the "gee-whiz" article: the one that tells you all sorts of stuff that you didn't know you didn't know, or that you are fascinated to find out about. Granted, even I didn't want to know as much about the Swiss army as McPhee decided to tell his New Yorker readers. And maybe McPhee got too fascinated by geology, leaving some of us wishing for more stuff like Oranges or The Pine Barrens. And maybe Tracy Kidder has lately been leaving McPhee in the dust. But I don't know anyone who writes better prose -- fiction or non-fiction.

The prose is still good in this volume, but it's on the whole disappointing. What strikes me most, especially about the longer pieces in the book, is the lack of structure in McPhee's essays. In "Season on the Chalk," he hops about from place to place in England and France with only the loosest of transitions; he lards "Spin Right and Shoot Left" with lists and catalogs, such as the roster of fifty-three colleges that sent coaches to an exhibition of potential varsity lacrosse players; his piece on the U.S. Open golf tournament, "Rip Van Golfer," is distractingly scattered among observations of place, observations of players, and observations of himself as observer. It doesn't help that I have little interest in either lacrosse or golf -- McPhee used to be able to hold my interest in even things that I wouldn't be inclined to read about.

Still, no magazine writer that I know of finds more curious and illuminating things to say about whatever he writes about. I just wish for an editor that would prune his excesses.

Great Short Works of Herman Melville

Perennial Classic, 1969

Listening to Benjamin Britten's opera Billy Budd not long ago, I realized how long it has been since I read Melville's story, so that's what inspired me to bring out this volume.

There are really only four "great" stories in the book:

- "Bartleby, the Scrivener," that astonishing imaginative bridge between Charles Dickens and Franz Kafka.

- "The Encantadas," an imaginative travelogue to the Galápagos, seen not as Darwin's laboratory of natural selection nor as the ecotourist's endangered paradise, but as the Fallen World in its raw essence.

- "Benito Cereno," the most mechanically structured of Melville's tales but also the one that raises the most unsettling questions about its theme and tone.

- "Billy Budd," that inexhaustible fable about innocence and experience, intellect and nature, beauty and ugliness, good and evil, as well as one of the nineteenth century's most provocative, if veiled, explorations of same-sex attraction.

Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

Modern Library, 1950

Having done the shorter works, how can I not do the whale? My text is an old, quite yellowed paperback that contains my signature from back when you could read my handwriting.

The ideal reader of Moby-Dick would be someone as obsessed with the book as Ahab is with the whale. Or at least someone as obsessed with it as Ishmael is with telling his story. But failing that, a good reader has to be prepared to work hard. Melville's grandiloquence would have been easier for his readers in 1851 to take, familiar as they were with the Bible, with Milton, with Shakespeare, in ways that even liberally educated readers aren't today.

Still, a reader should also take to heart the words of the great rock critic Lester Bangs: "The first mistake of art is to assume that it's serious." Moby-Dick is "serious" in the sense that it is as epic as the Iliad, as tragic as King Lear and Hamlet -- the two plays from which it most often draws. But it is not serious in the sense that it has to be taken as a sermon, a morality play, a philosophical discourse, or an allegory about good and evil, sin and redemption, or man and nature. It has elements of all of those, but it also plays with them, satirizes them, turns them inside out and examines them.

It must be remembered at all times that this is a story told by one Ishmael, who is a little bit crazy and a little bit like all of us. He sees things the way he sees them, and he is not always right in what he sees. All of the characters in his story are filtered through his consciousness -- we never see Ahab, or Starbuck, or Queequeg, or anyone else as they "really are" but as Ishmael sees them. He sees them as fallible human beings, because that's what he is. But he also sees them as demons or demigods because he's deeply romantic, and it's the ironic disjunction between the human beings that they are and the mythic figures that he makes of them that gives the novel its great internal energy. Ishmael's insights are full of contradictions: Is Queequeg a cannibal or the noblest of savages? Is Ahab truly insane? Is Starbuck a figure of integrity or weak and indecisive? Is whaling a noble pursuit or a corruptly dangerous expenditure of human and animal life to provide a luxury item?

Is Moby-Dick melodramatic and wildly overwritten? Oh, my, yes. But anyone who can't tolerate that has no business reading anything but the latest bestseller. Literature has always been stretched and forced to grow by its overreachers, its Dickenses and Dostoevskys and Victor Hugos and Prousts and Joyces and Faulkners and Pynchons. And Melvilles. By writers who refuse to play it safe. Moby-Dick never plays it safe. It's a wild farrago of tall tales and mock-heroics and absurdities along with heart-searing realities, radical visions, and prophetic insights. It is irreducible in its greatness, and anyone who meets its challenges is inevitably rewarded.

The Emperor's Children, by Claire Messud

Vintage Books, 2007

Claire Messud is one of those writers I keep hearing that I should read, and since this review copy arrived, I've been waiting for the opportunity. Here it is.

Once you learn that the novel takes place in New York City in 2001, you've seen Chekhov's gun: the one that, if it's shown in the first act, has to go off in the third. But whereas 9/11 looms for the reader as sections of the novel proceed from March to May to July to September and finally to November, when the summing-up takes place, it doesn't loom at all for the characters who, like the rest of us, proceed with their lives in blissful ignorance of the change coming to their lives. But The Emperor's Children is not a "9/11" novel. The events of that day hasten some of the changes that take place for the characters, but the changes are inherent in the relationships among them and would have occurred even in a less world-historical context.

The other thing that The Emperor's Children isn't is yet another "bright lights, big city" novel about smart young people taking on Manhattan. I mean, it certainly looks like one: the central characters are three friends from college -- Brown, to be precise -- who are just turning 30. Danielle Minkoff produces documentaries for public TV, Julius Clarke has made a name for himself as a critic at the Village Voice and elsewhere, and Marina Thwaite ... well, Marina's father is rich, so she hasn't settled on a career, but is working on a book. Marina's father, Murray Thwaite, is a "public intellectual," a well-known liberal commentator whose bestsellers, lecturing gigs, and magazine articles have earned him enough fame and fortune that he can afford an apartment on Central Park West.

Into their lives comes Murray's nephew, Frederick "Bootie" Tubb. He has grown up in the same bleak upstate New York town that Murray grew up in. And Bootie hopes to follow in his uncle's footsteps. Disillusioned with almost everything, but especially with college, Bootie drops out and eventually winds up staying with the Thwaites and becoming Murray's amanuensis.

While researching a documentary subject in Australia, Danielle meets Ludovic Seeley, a journalist who is moving to New York to start a trendy new magazine, The Monitor, bankrolled by a right-wing Aussie media mogul whose name isn't Murdoch but might as well be. In New York, Danielle introduces Ludo to Marina, and they fall for each other, even though Ludo is scornful of Marina's father's ideas. Ludo fancies himself the new Napoleon, who will conquer the world, or at least New York, by persuading everyone of the virtues of his way of looking at things: a tactic once phrased by another empire-builder, Karl Rove, as "creating our own reality."

Julius, meanwhile, meets an up-and-coming young businessman, David Cohen, and becomes his "kept man," moving into his Chelsea apartment. David so mesmerizes Julius that he stops hanging out with Danielle and Marina, his closest friends. Julius has always wondered whether he's the plodding Pierre or the lively Natasha of War and Peace, one of the many allusions to the Tolstoy novel that Messud weaves through her own.

Messud's tone is dryly satiric, but never viciously so, thanks to Messud's gift for characterization and the skill with which works out the relationships among Danielle, Marina, Julius, Murray, Bootie, Ludo and David. Thought David, perhaps because of his secretiveness, is the least vivid of the characters, and the working out of his relationship with Julius is the least successful part of the novel. Critics have invoked such names as (obviously) Tom Wolfe, Jane Austen, and Edith Wharton in writing about the book, and Messud herself has provoked the comparison to Tolstoy. I think the shrewdest comparison is one made by Maureen Corrigan to Fitzgerald, who gave us a portrait of an age. So does Messud, by the very nature of the place and time she writes about.

Paradise Lost, by John Milton

Odyssey Press, 1962

It's generally regarded as a great poem, but is it a good one? By that, I mean, is it more than what one critic called it, "a monument to dead ideas"? What relevance does it have to those of us who do not share Milton's view of humankind?

"The plan of Paradise Lost has this inconvenience, that it comprises neither human actions nor human manners. The man and woman who act and suffer are in a state which no other man or woman can ever know. The reader finds no transaction in which he can be engaged, beholds no condition in which he can by any effort of imagination place himself; he has, therefore, little natural curiosity or sympathy." Thus spake Samuel Johnson, who gets at a key problem of the poem: its lack of humanity. As a poem of ideas, it has to stand or fall on the value of those ideas, and for many of us for whom Christian theology, and particularly the concept of fall and redemption, has no appeal, the ideas simply don't attract. But Johnson did subscribe to those ideas, and he still seems to have found Paradise Lost lacking: "Being therefore not new they raise no unaccustomed emotion in the mind: what we knew before we cannot learn; what is not unexpected, cannot surprise."

The harshest criticism advanced by Johnson is this: "Paradise Lost is one of the books which the reader admires and lays down, and forgets to take up again. None ever wished it longer than it is. Its perusal is a duty rather than a pleasure. We read Milton for instruction, retire harassed and overburdened, and look elsewhere for recreation; we desert our master, and seek for companions."

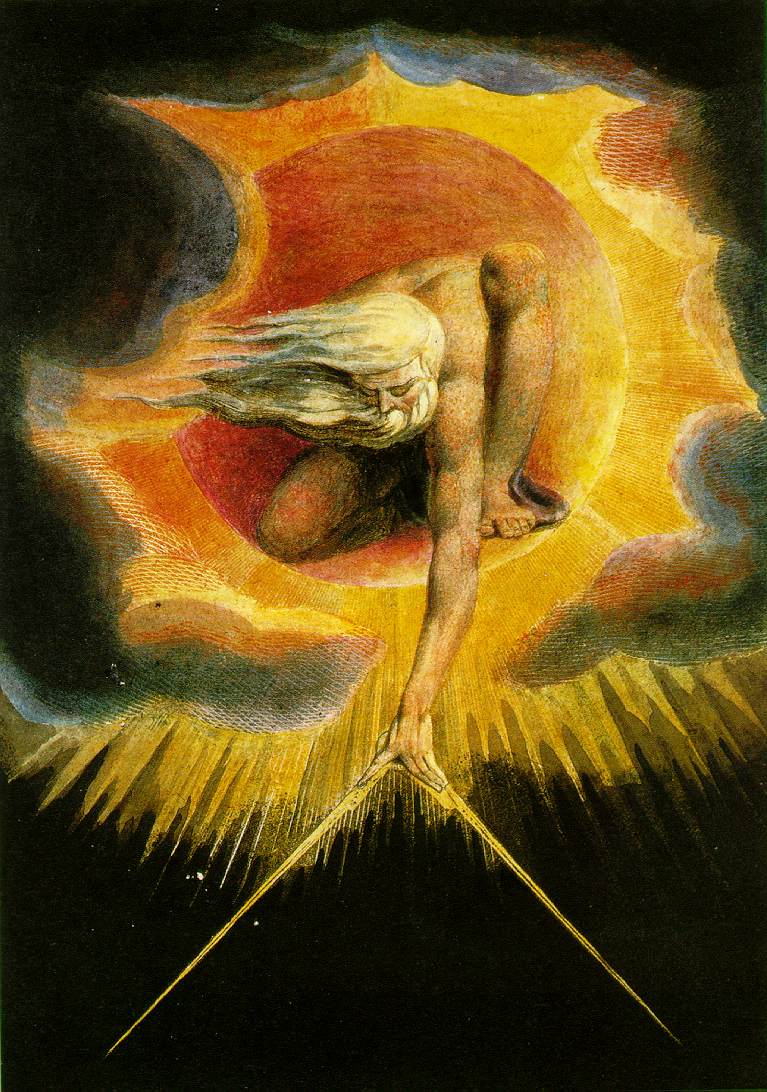

But where do I, the non-believer, stand on Paradise Lost? I differ from Johnson in that I remembered to take it up again. I remembered the great organ-like tones of Milton's verse, the strange passion that drove him to undertake such a huge task, and the manifest ambiguities of his portrayal of Satan, that impelled the Romantics like Blake and Shelley and Byron to view the devil as Milton's unacknowledged hero.

Paradise Lost is, I think, a decadent work in that it demonstrate the cracks that had already appeared in Christianity with the Reformation and would only widen through the Enlightenment until today, when the great majority of educated people reject biblical literalism and such contingent matters as the subjugation of women. Milton's poem is a mannerist work, one in which the style much overshadows the subject matter. It can be read for pleasure in seeing a skilled poet working at top form, but it can never again communicate to most of its readers something that feels like truth.

The Tragedy of Arthur, by Arthur Phillips

Random House, 2011

I have read (and reviewed) all of Phillips's novels save one (The Song Is You), and given my somewhat qualified liking for those, and my interest in Shakespeare, this one seemed particularly appealing, so I bought it.

The novel is certainly a tour de force: A complete fake Shakespeare play with an introduction in which the narrator, one Arthur Phillips, tells the wild tale of how the play, long unknown, was "discovered," how he agreed to have it published and to write an introduction, and how he tried to prevent its publication once he became convinced that the play was a fake.

The Arthur Phillips of the novel happens to have written four novels, all of which have the titles of the "real" Arthur Phillips's books. His father is a convicted forger, who has spent most of Arthur's life in prison for various acts of fraud, so there is every reason to be suspicious that the quarto of The Tragedy of Arthur by William Shakespeare is a phony. But Arthur's twin sister, Dana, believes it to be genuine, and one by one the experts who examine it fall in line as well. Arthur is convinced at first that the play is genuine, but he makes a discovery that reinforces his natural doubts. But no one else, including his publisher, Random House, is persuaded to his side.

But though the pastiche Shakespeare that Phillips has created for the novel is an impressive job, no one is really likely to mistake its rather ploddingly regular iambic pentameter for real Shakespeare. This is no great objection to its function in the novel, however, which is really about many other things: the nature of literary reputation, the foibles of fame, the expectations of publishing, and most of all, the relationship of fathers and sons. As Arthur's sister, Dana, observes, the Arthur of the novel is " the first person ever to suffer from a double oedipal complex, and one of your dads is four hundred years old."

Where the novel fails is in its rather unnecessary elaboration of Arthur's complicated life story, including an unconvincing fling with Dana's lover, a woman named Petra, that eventually forces Arthur to capitulate to the demands that the play be published.

Mason & Dixon, by Thomas Pynchon

Picador, 2004

I've never read any Pynchon, never feeling that I could commit the time and the attention. My mistake, I suppose. But now I have the time, so I picked up the one novel by Pynchon on my shelves, a review copy of the paperback edition that I took with me when I left the Merc.

In literature, there's a fine line between cleverness and obscurity, between stimulating and exasperating. James Joyce, for example, crisscrossed that line incessantly in Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake he hopped over it and ran away, leaving the rest of us behind. It's a line that Pynchon dances merrily along in Mason & Dixon, which is, of course, a book about a line. That this is a work of genius is undeniable: It's a great, mad farrago, a pastiche of 18th-century English novelists like Smollett and Sterne, leavened with undeniably American touches of Mark Twain and Faulkner, among many others. You need a reference library close at hand to savor it even partially. (I relied on Google and Wikipedia for allusions and geography.)

And yet -- here again the comparison to Ulysses is useful -- it's rare that a book this hard to read, by an author so determined to pull the rug of comprehension out from under your feet, is also this much fun. Not for everyone, to be sure. But if you've got the time and patience, it's worth a try.

The World of Christopher Marlowe, by David Riggs

Henry Holt, 2005

David Riggs has been a friend of mine since graduate school, so I'm a little embarrassed to be just getting around to his book on Marlowe, which received glowing reviews (including the front cover of The New York Times Book Review). My excuse is that I wanted to wait and read Marlowe's plays again, which I hadn't done since ... well, graduate school.

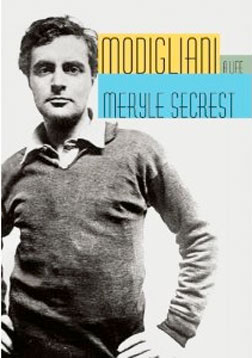

Modigliani: A Life, by Meryle Secrest

Knopf, 2011

Sometimes you decide to read a book just because you don't know anything about the subject. That's the case with this one. I had read one biography by Meryle Secrest, of Richard Rodgers, and I liked it. But I had an interest in Rodgers to start with. In Modigliani's case, all I knew was that he did paintings of long-necked women with almond-shaped faces, and my attitude was pretty much that if you've seen one of those paintings, you've seen them all. So when the bound galley of this book showed up, I decided I'd check it out to see why Modigliani deserved a biography.

The premise of Secrest's biography is that he has been misrepresented as a self-destructive drunk who just happened to paint a lot of good pictures. She puts the blame for his erratic behavior and his alcoholism on tuberculosis, which because it was a disease that once had the stigma that AIDS more recently carried, was something he was made an effort to conceal. And that his drinking was really to keep him from coughing so much. I think she makes her point, though at the expense of reiterating it unnecessarily.

Oddly, it is not until the very end of the book that she comes to grips with Modigliani's stature as an artist, admitting that in academic and critical circles, his work is not always considered of the highest rank. It fetches high prices at Sotheby's and Christie's, and is generally popular, but the same could be said of Salvador Dalí, whose work lacks critical cachet these days. On the scale of great moderns, does Modigliani belong in the company of Picasso and Matisse, or in the company of Dalí? It's probably an unanswerable question, but to my mind, after reading Secrest's book and looking at a lot of Modigliani on the Web, I'd say that Modigliani was a great colorist with a superb skill for line and composition, but that on the other hand a lot of his portraiture verges on caricature. There is a hint of mannerism in his work that makes it tiresome after a while.

But Secrest's analysis of some of his paintings is persuasive, and if anything, has sent me back to look at his work with a keener eye -- no, if you've seen one Modigliani, you haven't seen them all.

All's Well That Ends Well, by William Shakespeare

The Arden Shakespeare

Routledge, 1994

Time for another run-through of Shakespeare's plays. The last time I did this, I wrote an article for the Mercury News about reading all the plays in alphabetical order, which meant I had to start with All's Well That Ends Well. I called it one of Shakespeare's worst plays, which rather shocked an academic friend of mine who is uneasy about such critical judgments. So I promised myself that this time around I wouldn't start out with such a harshly prejudicial point of view.

I still hold that if you're going to read all of Shakespeare's plays, the only sensible way of doing it is to proceed alphabetically. The chronology of the plays' composition is still unsettled, which makes that approach problematic. You could read all the comedies together, then the histories, then the tragedies, but even there the question of which order to read them in looms. So alphabetical seems as sensible an order as any. (I thought for a moment of reading them in reverse alphabetical order this time, starting with The Winter's Tale, but that would also raise the question of whether to read the Henry VI plays before Henry V, and then Henry IV, which seems sort of silly to me.)

There's also the question of what edition to use. I have a couple of big one-volume editions on hand, but they're too heavy for comfortable reading. There are a lot of different paperback editions to choose from, but back in grad school I picked up several of the Arden editions in second-hand bookshops. They have introductions with critical commentary and notes on the textual sources, as well as comprehensive footnotes, a complete scholarly apparatus. The apparatus is maybe a little too scholarly for a casual reader, but if you can avoid getting too bogged down in the footnotes -- as Samuel Johnson said of footnotes, "The mind is refrigerated by interruption" -- the type is clear and readable and the format comfortable. So I'm staying with Arden.

And so, once more unto the breach.

As it turns out, All's Well is a far more interesting play than I remembered. Maybe during my first run-through of the Complete Works of William Shakespeare I was too impatient to get to the Major Works and paid too little attention to the lesser ones. I now think that AWTEW suffers mostly from unfamiliarity, and particularly from the infrequency of productions of the play. It is, let's face it, a damn hard play to read: You have to put in so much work mastering the vocabulary, struggling with the syntax, parsing the grammar, that it's easy to lose sight of the fact that this is essentially a script. It's meant to be performed, and if you can't encounter it in performance, you have to add the problem of staging it in your head to the problems already mentioned.

It's much easier to stage a play in your head if you're already familiar with it, as most of us are with oft-performed plays like Romeo and Juliet or Hamlet or A Midsummer Night's Dream. But most of us have never encountered Bertram or Helena or Parolles on either stage or screen, so it's hard to know what to make of them at first. There are a few excerpts from the 1981 BBC TV production of AWTEW on YouTube (I posted them in the blog) that help, but for the most part you're on your own.