Preface and Acknowledgments; Chapter 1: The Problem; Chapter 2: The Clues

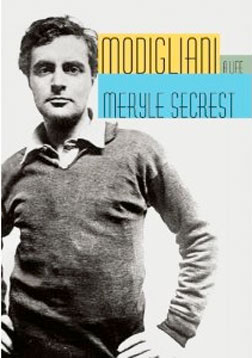

Books don't usually begin with acknowledgments, but Secrest obviously owes a debt of gratitude to Marc Restellini, whose enthusiasm for Modigliani and whose curatorial efforts in mounting exhibitions of his work inspired her. "Restellini by most accounts has become the leading authority on the work of Amedeo Modigliani," she writes, and he began helping her with an introduction "to a pivotal figure, Luc Prunet, the great-nephew of Jeanne Hébuterne, Modigliani's last love, who committed suicide within days of his death in 1920. This event, Restellini thought, had done most to fix in people's minds the idea of a dissolute Bohemian, doomed to destroy everything and everyone he touched."

Restillini's resistance to this conventional idea about Modigliani also shaped the direction of Secrest's biography, and for a time they considered co-authorship.

Secrest had earlier written a biography of the American expatriate artist Romaine Brooks, a contemporary of Modigliani whose "success in 1910 was immediate," whereas "Modigliani's achievements took decades to be appreciated." Today, it is Brooks who is largely unknown to the general public, while "Modigliani's reputation continues to soar, to judge from the prices paid for his paintings."

In the National Gallery in Washington, Secrest happened upon a room containing eight Modigliani paintings and one of his sculptures, from the collection of Chester and Maud Dale who had bought them "in the early 1920s, when they could almost be had in job lots."

The first painting over which Secrest lingered was Modigliani's portrait of Monsieur Deleu, from 1916:

|

"The expression, at first glance a caricature, was in fact full of

dexterously applied details, such as a touch of light in the left eye, a

shadow under an eyebrow, and the play of volumes around the mouth and

chin.... The sense of enigmatic intent extended to the dappled light and

shade on the sitter's jacket and the close attention given to what is

usually least considered, i.e., the background. Each stroke of the brush

seemed to have been placed with a feeling of finality, even

inevitability." --Secrest (Image source)

|

Next to it was

Madame Amédée (Woman With a Cigarette), which was painted two years later, a "depiction of a heavyset woman in a black dress, hand on hip and a cigarette dangling between her fingers."

|

| "That air of disdain, those raised brows, the puckered mouth -- could there be a hint of self-doubt in her pose? The impression is reinforced by the artist's sloping floor and the realization that his model is not actually sitting on her chair but floating above it. Hauteur, insouciance, pretense -- all this melts before the penetrating gaze of the artist, who has made his feelings known with such delicate irony." --Secrest (Image source) |

Gypsy Woman With Baby was painted in 1919, shortly after Modigliani had become a father.

|

| "Fragile grays, going from blue to green, are harmoniously intertwined within outlines that have been softened and blurred, the paint broken up into thumb-like patches of color. The mother, hardly more than a girl, with her high coloring, skewed nose, pretty mouth, and sweet, lost look, presses her baby against her as if clinging to a life raft.... As a final, masterful touch, the artist has added, in his subject's otherwise neat coiffure, a single escaping wisp of hair." --Secrest (Image source: Wikipedia) |

|

| "Modigliani ... painted [Chaim Soutine's] portrait a number of times. Here he is [in 1917], staring out of the frame, a seated figue with tumbling hair and ill-matched clothes, his hands placed awkwardly in his lap, his eyes half closed and peasant nose spreading across his expressionless face. He is ugly, and yet." --Secrest (Image source) |

Modigliani's "chef d'oeuvre,

Nude on a Blue Cushion, one of the painter's series of grand horizontals, [was] painted three years before his death."

|

| "This is a girl who wants to be liked and is not at all sure of the reception, as is suggested by fastidious painterly details, such as the light and shade around the forehead, a touch of pink beside the nose, and the hint of a line under one eye. At close range, one discovers ... the smidgen of blue on a wrist which picks up the color of the cushion, the patch of pink on a knee, the dot at the corner of an eye, and the same judiciously considered background." --Secrest (Image source) |

A "single piece of sculpture, a limestone head of a woman, [stands] on a pedestal in one corner of the room."

|

| "The head, carved from a rectangular piece of stone, was consequently elongated, its nose radically long, mouth barely indicated, eyes enigmatic and impassive. One thought, as Bernard Dorival wrote, of the religious power found in Khmer and Chinese sculptures. Monumentality -- other-worldliness -- the transcendental -- such thoughts rose to the surface and whirled around in my head." --Secrest (Image source) |

The legend of Modigliani as a self-destructive artist began to develop not long after his death. "In 1926 André Salmon, poet and journalist, published a seeming celebration of Modigliani's art that made frequent references to the artist's apparent addiction to drugs and society," and this fed an image of the "artist at odds with society," analogous to others such as Gauguin and Van Gogh.

He was a visionary, a poet and philosopher, even a mystic. Or he was a minor character, whose romantic life story had led some to place more importance on his work than it deserved. His nickname was Modi, which Salmon was the first to transmute into "maudit," i.e., accursed.

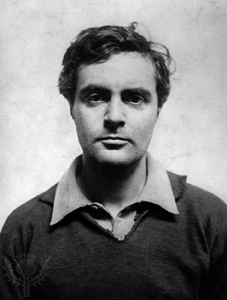

Among the facts about his life were that he was "the youngest of four children from an educated but impoverished Italian Jewish family," and that he "came to Paris in 1906 at the age of twenty-two to make his fortune." He was also "strikingly good-looking." But his painting failed to gain critical notice. There were "no reviews at all for his [one-man show] in 1917, and few mentions in the French press during his lifetime." He died at thirty-five, and his lover, Jeanne Hébuterne, killed herself and their unborn child two days later. They left a two-year-old daughter.

The tragic story inevitably attracted fiction writers, and in 1958 a French movie based on his life,

Montparnasse 19 (in America,

Modigliani of Montparnasse), was made, starring Gérard Philipe as Modigliani. The Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, who had had an affair with Modigliani, called it "extremely vulgar."

|

| Poster for the 1957 film based on Modigliani's life (Source) |

Missing from many of these accounts were some key facts, such as the two "life-threatening" illnesses that he had suffered before reaching the age of seventeen, and his "lifelong battle with tuberculosis" and "the toll it exacted: physical, emotional, and social." In many of the biographies and fictions there is, Secrest asserts, a "clear goal of capitalizing on the tragic circumstances of his life and almost simultaneous deaths of himself and his mistress in 1920."

|

| Billy Klüver and Julie Martin (Source) |

Setting out on her quest for the truth about Modigliani, Secrest made contact with Julie Martin and Billy Klüver, experts on the "complicated interrelationships among the artists, sculptors, poets, writers and musicians in Paris" in the early twentieth century. They agreed with Secrest's premise that Modigliani "was a remarkable man who had been dismissed as a clownish figure who just happened to have painted some unforgettable canvases." Martin and Klüver introduced her to numerous important sources, including Restellini, and told her of the interviews conducted by Pierre Sichel in 1963-64 with many of the people who had known Modigliani. After writing a biography of Modigliani, Sichel had given the interviews to Boston University.

Julie Martin also directed Secrest to the manuscript of the family history written by Modigliani's mother, Eugénie Garsin-Modigliani. It had been a source for Modigliani's daughter Jeanne's biography of her father, but Secrest discovered that Jeanne had made little use of the material in it. The Garsins were "Sephardic Jews who had lived on the Mediterranean coastline for centuries," and claimed to be descended from the philosopher Spinoza. They were "a family much more apt to take pride in intellectual prowess than financial dealings" and who "moved with ease between cultures and social groups." Eugénie, one of seven children of Isaaco and Regina Garsin, grew up in Marseille.

In 1870, when Eugénie was fifteen, the family, which "had constantly shuttled between Marseille and Livorno, turned back toward Italy," in large part because of the Franco-Prussian War. Her father and grandfather also decided that it would be a good time to make plans to marry Eugénie to "a member of a prominent Livornese family."

Physically the Garsins were small and dark with "alert, expressive, changeable faces," Eugénie wrote. They were subject to illnesses: liver disease (which suggests alcoholism), tuberculosis, and psychological disorders, as well. The Modiglianis were taller and well built, held themselves well, were of "phlegmatic temperaments," were robustly healthy, and lived into old age. Whereas the Modiglianis were "more inclined to enjoy life than strain their intellects," Eugénie wrote with her usual acerbity, the Garsins were almost fanatically well-read, eager scholars.

Also unlike the Garsins, "the culturally illiterate Modiglianis ... had a genius for business." The family fortune was based on minerals: the mining of lead and zinc in Sardinia and Lombardy.

|

| Eugénie and Flaminio Modigliani (Source) |

Flaminio Modigliani was thirteen years older than Eugénie; he co-managed the family's mine and thirty-thousand acres of land in Sardinia. They married in January 1872, but Eugénie saw her husband only "ten days every Easter and fifteen days every summer; for the remainder of the year she lived alone." Their first child, Emanuele, was born in the winter of 1872. Eugénie's mother came to visit, but she was already suffering from the tuberculosis from which she would die in May 1873. The Garsins were also experiencing financial trouble, and the combination of that with his wife's death caused Eugénie's father to have a nervous breakdown.

The Modiglianis also went through a financial crisis when the price of metals began to drop in 1881, and in 1883 they declared bankruptcy. By 1884, "Flaminio and Eugénie had three children: Giuseppe Emanuele, Margherita, and Umberto," and she was pregnant with Amedeo. The house they were living in was in liquidation, but "the Modiglianis discovered an obscure Italian law that prevented the authorities from removing the bed on which a pregnant woman was about to give birth. One imagines the jewels, silver, clothes, laces, silks, curtains, bedspreads, blankets, linens, pillows, draperies, cushions, objets d'art, rugs and much else piled upon the very large bed on which the mother-to-be presumably lay." But in fact, Amedeo was born on "an enormous kitchen table with a black marble top" on July 12, 1884.

No comments:

Post a Comment