|

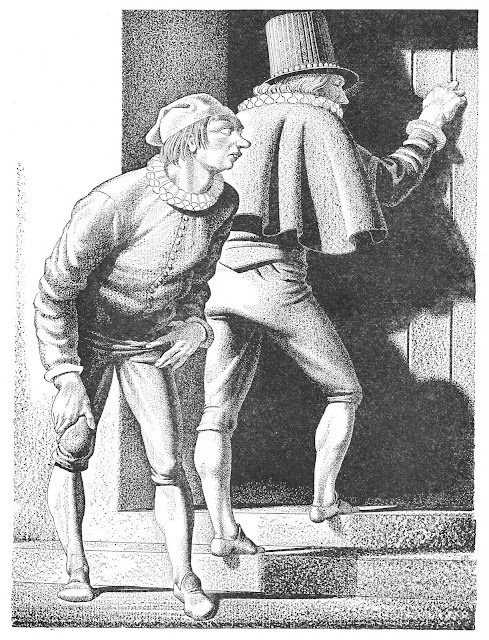

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent. (Antipholus of Ephesus: Who talks within there? ho! open the door. The Comedy of Errors, Act 3, Scene 1) |

Introduction, by R.A. Foakes

Introduction, by R.A. FoakesWe know The Comedy of Errors only because it was published in the First Folio in 1623, having been registered by Edward Blount and Isaac Jaggard in November of that year, a sign that the play "had not, as far as they knew, or we know now, appeared in print before." That the characters are named inconsistently in the Folio suggests that the typesetter was working from a text very close to the author's manuscript -- if he had been working from a prompter's copy, there would have been more consistency in the names. "On the whole the stage-directions seem to be the author's; several provide information superfluous to a prompter's needs," but which suggest that Shakespeare was making notes to remind himself that Adriana was the wife of Antipholus of Ephesus and that Pinch was a schoolmaster. And some inconsistencies in the directions for entrances and exits suggest that the play was first divided into acts for the Folio publication.

It is unnecessary toEveryone agrees that it's an early play. It's also the shortest one in the Shakespeare canon, at only 1,800 lines. (Hamlet is the longest.) The earliest known performance of it was at Gray's Inn in December 1594, but scholars have combed the play for evidence of earlier composition. There are what seem to be allusions to the Spanish Armada, the civil war in France, and plays by Marlowe and Lyly that would suggest that it was written no earlier than 1588, but scholars being what they are, even these possible references have been challenged by those who want an earlier or a later date. There is, for example, "the possibility that the phrase, 'armadoes of carracks' (III.ii.135), may refer, not to the Great Armada, of 1588, but to the Great Carrack, the Madre de Dios, a Portuguese galleon captured and brought to England in September 1592." This has resulted in a "tendency to fix on 1592 as the date of composition." But the performance date of 1594 is the best evidence we have to go on.introduce a prompter or scribes to account for the peculiarities of this text; they may all be explained in terms of an author inattentive to petty details, a printer who added act-divisions, and compositors who solved an occasional puzzle as best they could.

Some scholars have also pointed out similarities in the play to the narrative poems of 1593, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, as well as links to Love's Labour's Lost and The Two Gentlemen of Verona, which seem to be roughly contemporaneous with The Comedy of Errors. "These linkages tend to reinforce the supposition that The Comedy of Errors was written not long before or immediately after the long spell of plague which caused all acting to be prohibited in London throughout most of the year 1593, and which probably turned Shakespeare to writing his narrative poems."

The principal source is Menaechmi, by Plautus, of which there were several sixteenth-century Latin editions. The Roman play centered around the confusion caused by a single set of twins, both named Menaechmus, but "Shakespeare not only multiplied the twins and the possibilities of error in his play by creating the Dromios, he also altered the emphasis of the Plautine plot" by eliminating several characters and placing significantly more emphasis on one of the Antipholuses: "Antipholus of Syracuse has nearly a hundred lines more than his brother, as well as a more sympathetic role."

A translation of Menaechmi by William Warner was published in 1595, which has led some to believe that Shakespeare saw the translation in manuscript. "However, even those who have made as much as possible of the verbal similarities [between Shakespeare's play and Warner's translation] have not been able to build up a convincing case that Shakespeare knew Warner's translation; indeed, the reverse could be true, that Warner echoed Shakespeare."

Shakespeare also seems to have borrowed from another play by Plautus, Amphitruo, which tells of Jupiter's seduction of Alcmena by disguising himself as her husband, Amphitryon. "In this play there are two pairs of twins, masters and servants, who cannot be distinguished by their friends or by Alcmena, and Shakespeare doubtless took a hint from this play for the development of the twin Dromios in addition to their twin masters."

Shakespeare altered the tone of his Latin sources considerably, not merely by putting an emphasis on marriage and courtship, rather than on the husband's relations with a courtesan, but also by giving his play a certain Christian colouring, and developing ideas of sorcery and witchcraft.... Shakespeare also transferred the setting of The Comedy of Errors from Epidamnum, the scene of Menaechmi, to Ephesus, recalling for himself and his audience St Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians.Other sources may have included the story of Apollonius of Tyre, as told by John Gower in Confessio Amantis, Plautus's Rudens, and such Italian plays as Gl'Inganni and L'Ammalata, which also hinge on mistaken identity. John Lyly's play Mother Bombie, which was printed in 1594 but had been acted as early as 1590, also includes a servant named Dromio, and there are a number of phrases in Lyly's play that seem to be echoed in The Comedy of Errors.

Unlike most of Shakespeare's plays, The Comedy of Errors "preserves a unity of place and of time, for the entire action takes place within Ephesus and within the space of one day; and, in addition, it seems to require only four playing-areas, or at the most five." There is the street, the house of Antipholus of Ephesus (whose sign is the Phoenix), the Courtesan's house (the Porpentine, i.e., Porcupine), and the Priory, which probably bore the sign of a cross. An upper gallery may also have been used.

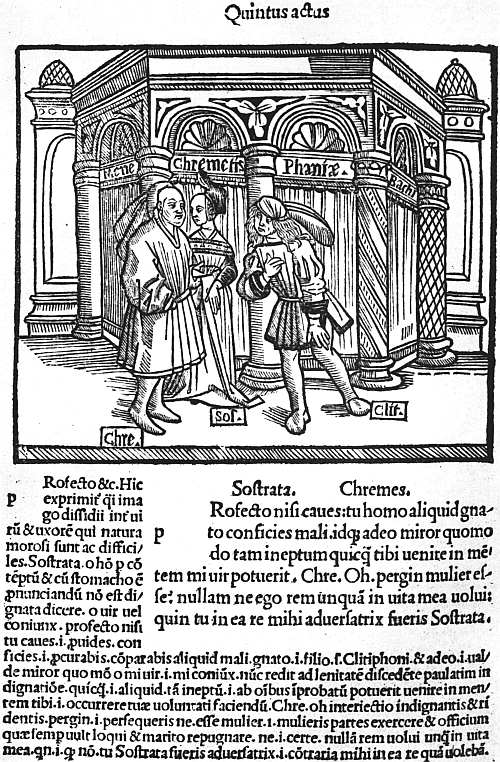

It is tempting to suppose that this short play, with its classical background, was designed for performance in a hall with no gallery, and for an audience used to "houses" on stage, and perhaps familiar with the kind of arcade setting to be seen in illustrations to several early editions of Terence.

|

| A page from the edition of Terence's comedies published by Johann Trechsel in 1493. The artist imagines a Roman stage with an arcade that has entrances labeled for each house represented in the play. (Source: Project Gutenberg) |

The Comedy of Errors has not been the object of much critical attention beyond acknowledgement that it is a "clever adaptation of Roman comedy," and that it is "the 'best plotted of Shakespeare's early comedies,'" though some have seen it "as an attempt to combine romance and farce, with disastrous results." But Foakes points to the serious element in the plot, the story of Egeon: "in spite of the implausibility and fantastic coincidences of Egeon's tale of the shipwreck, we are directly affected by his wretchedness, his dramatic presence on stage as a lonely, pathetic figure, lacking money and friends, and sentenced to die at the day's end." This "sombre tone established in Act I is never entirely dispelled until the end of the play, and is carried over immediately into Act II in the suggestions of sorcery and witchcraft in Ephesus."

The question of identity, and the horrifying loss of it, is also at the heart of the play. Foakes asserts that "Shakespeare had a larger purpose than merely to soften the harsh world of Plautine comedy, or exploit more fully the ancient comic device of mistaken identity. His modifications of the sources are used to develop a serious concern for the personal identity of each of the main characters," as well as the "disruption of family, personal, and social relationships." In addition to the invocation of witchcraft, there is also the fear of loss of sanity: Antipholus of Ephesus "regards himself as alone sane in a world gone mad. He is given some force of character, and a tendency to violence, so that when he is shut out of his own house, he is driven to bewilderment and to passionate exclamation." There is "a sense of evil at work in Ephesus" that feeds into the role of the Priory in resolving the problems of the characters and "lends a faintly holy and redeeming colour to the end of the play."

This redemptive aspect is characteristic of Shakespeare's comedies:

For the sense of deliverance in them is a means to an end -- the end being a re-establishment of responsibility among individuals in a society in the light of a test undergone, or a penance endured, an acceptance of moral bondage in the full understanding of what this means.... The Comedy of Errors, then, differs from its Plautine models in a characteristically Shakespearian way; later on Shakespeare was to absorb the pole of violence or suffering into his comedies, as in Twelfth Night or Much Ado, or to make the enveloping action, as in As You Like It, slide so smoothly into the central plot that it is hardly noticed as a frame at all.

After the 1594 Gray's Inn performance and a performance at court in 1604, there are no other recorded performances in the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century there were some adaptations of the play, and in 1819 Frederick Reynolds turned it into an opera. It was revived in more or less original form in the nineteenth century, and a 1915 production at the Old Vic provided a debut for Sybil Thorndike in the role of Adriana. Theodore Komisarjevsky's production at Stratford in 1938 was a hit. The same year, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's musical comedy version, The Boys From Syracuse, was performed on Broadway, and there have been several musical adaptations since then.

No comments:

Post a Comment