Myth: Myth and Literature (Thomas Mann, T.S. Eliot). Self-Consciousness: Introduction; Self-Realization (Jean-Jacques Rousseau)

Myth: Myth and Literature (Thomas Mann, T.S. Eliot). Self-Consciousness: Introduction; Self-Realization (Jean-Jacques Rousseau)_____

Thomas Mann: Psychoanalysis, the Lived Myth, and Fiction

When Mann gave his address, "Freud and the Future," in 1936, he was completing the third volume of his tetralogy, Joseph and His Brothers, his own exploration of myth. So he was interested in the way Freud's psychoanalytical theories connected with his own concept of mythology.

Mann recognizes the similarity between "Freud's description of the id and the ego" and "Schopenhauer's description of the Will and the Intellect" as "a translation of the latter's metaphysics into psychology."

The pregnant and mysterious idea ... developed by Schopenhauer is briefly this: that precisely as in a dream it is our will that unconsciously appears as inexorable objective destiny, everything in it proceeding out of ourselves and each of us being the secret theatre-manager of our own dreams, so also in reality the great dream that a single essence, the will itself, dreams with us all, or fate, may be the product of our inmost selves, of our wills, and we are actually ourselves bringing about what seems to be happening to us.... I see in the mystery of the unity of the ego and the world, of being and happening, in the perception of the apparently objective and accidental as a matter of the soul's own contriving, the innermost core of psychoanalytic theory.The Germanic syntax retained by H.T. Lowe-Porter in his translation of Mann's address is hard to follow. At its basis, Mann is endorsing Freud's theory that accidents like slips of the tongue are manifestations of the unconscious, hence not accidental at all, and extending that to Schopenhauer's concept of an immanent will working out the destiny of humankind. So things don't happen to us, we cause them to happen. Mann quotes Jung ("an able but somewhat ungrateful scion of the Freudian school"): "It is so much more direct, striking, impressive, and thus convincing, ... to see how it happens to me than to see how I do it." And he asks, "Would this unmasking of the 'happening' as in reality 'doing' be conceivable without Freud? Never!"

But Mann chides Freud for underestimating the power of philosophy, which Mann sees as a manifestation of the Freudian unconscious and/or Schopenhauerian will: "Has the world ever been changed in anything save by thought and its magic vehicle the Word? I believe that in actual fact philosophy ranks before and above the natural sciences and that all method and exactness serve its intuitions and its intellectual and historical will.... One might strain the point and say that science has never made a discovery without being authorized and encouraged to by philosophy."

Returning to Jung, he gives the apostate credit for discovering a "bridge" between Eastern mysticism and Western metaphysics: "It is true that the East has always shown itself stronger than the West in the conquest of our animal nature, and we need not be surprised to hear that in its wisdom it conceives even the gods among the 'given conditions' originating from the soul and one with her, light and reflection of the human soul." Mythology is a human emanation, and thus the gods depend on the existence of humans. Mann acknowledges that to Western religion the concept of God as anything but "absolute reality," as "one with the soul and bound up with it, must be intolerable ... equivalent to abandoning the idea of God." But he posits that even the word "religion," which may be derived from the Latin religare, to tie fast, "essentially implies a bond," and that Genesis speaks of "the bond (covenant) between God and man."

This idea underlies his own novel, he says: "Abram is in a sense the father of God. He perceived and brought Him forth; His mighty qualities, ascribed to Him by Abram, were probably His original possession. Abram was not their inventor, yet in a sense he was, by virtue of his recognizing them and therewith, by taking though, making them real." The mythmaker brings not only the myth into being, but also the god(s) to which the myth refers. And mythmaking is an essential human process: "For man sets store by recognition, he likes to find the old in the new, the typical in the individual." And "the typical is actually the mythical."

As a novelist, Mann says, he "took the step in my subject-matter from the bourgeois and individual" -- e.g., Buddenbrooks -- "to the mythical and typical," which established his connection with psychoanalysis: "The mythical interest is as native to psychoanalysis as the psychological interest is to all creative writing." Awareness of the work of ethnographers has led to a recognition that "the myth is the foundation of life; it is the timeless schema, the pious formula into which life flows when it reproduces its traits out of the unconscious."

Through myth we gain "a knowledge of the schema in which and according to which the supposed individual lives, unaware, in his naïve belief in himself as unique in space and time, of the extent to which his life is but formula and repetition and his path marked out for him by those who trod it before him."

Actually, if his existence consisted merely in the unique and present, he would not know how to conduct himself at all; he would be confused, helpless, unstable in his own self-regard, would not know which foot to put forward or what sort of face to put on.... The myth is the legitimization of life; only through and in it does life find self-awareness, sanction, consecration.Historical figures such as Cleopatra and Alexander found the patterns of their life through myth, Cleopatra following the model of Aphrodite: "it was far more her erotic intellectual culture than her physical charms that entitled her to represent the female as developed into the earthly embodiment of Aphrodite.... Cleopatra fulfilled her Aphrodite character even unto death -- and can one live and die more significantly than in the celebration of the myth?" As for Alexander, "he walked in the footsteps of Miltiades" and set a pattern that was continued by Julius Caesar, whose "ancient biographers ... were convinced, rightly or wrongly, that he took Alexander as his prototype," and by Napoleon, who "regretted that the mentality of the time forbade him to give himself out for the son of Jupiter Ammon, in imitation of Alexander."

Jesus, too, worked with the consciousness of the patterns of the past:

His life ... was lived in order that that which was written might be fulfilled.... His word on the Cross, about the ninth hour, that "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" was evidently not in the least an outburst of despair and disillusionment; but on the contrary a lofty messianic sense of self. For the phrase is not original, not a spontaneous outcry. It stands at the beginning of the Twenty-second Psalm, which from one end to the other is an announcement of the Messiah. Jesus was quoting, and the quotation meant: "Yes, it is I!"So Mann proclaims his Joseph novels as "a narrational meeting of psychology and myth, which is at the same time a celebration of the meeting between poetry and analysis."

T.S. Eliot: Myth and Literary Classicism

As Eliot says in this essay about James Joyce's Ulysses in 1923, the novel hadn't "been out long enough for any attempt at a complete measurement of its place and significance to be possible." But Eliot gets some things very right about it: chiefly, that the mythic structure of the book is not just "an amusing dodge, or scaffolding erected by the author for the purpose of disposing his realistic tale." That the myth of Odysseus is organic to Ulysses has been obvious to us for a long time now, but Eliot was one of the few who got it at the time.

Much of the essay centers on Richard Aldington's criticisms of Ulysses. Aldington was a friend of Eliot's, though they later parted company when Aldington sided with Eliot's wife, Vivienne. Eliot and Aldington agreed on the virtue of what they called "classicism," as "a goal toward which all good literature strives, so far as it is good, according to the possibilities of its place and time." Eliot's classicism is "doing the best one can with the material at hand," and his criticism of Joyce centers on the question, "how much living material does he deal with, and how does he deal with it ... as an artist?" In Eliot's view, Joyce deals with it properly by breaking away from the novel as traditionally practiced.

If it is not a novel, that is simply because the novel is a form which will no longer serve; it is because the novel, instead of being a form, was simply the expression of an age which had not sufficiently lost all form to feel the need of something stricter.... The novel ended with Flaubert and with James.As Eliot admitted to the editors of The Modern Tradition, "To say that the novel ended with Flaubert and James was possibly an echo of Ezra Pound and is certainly absurd." But Joyce had found in both his narrative style -- the disjointed, often playful, show-offy technique that Aldington attacked as chaotic and Dadaist -- and in his use of the mythic structure "a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history."

Psychology (such as it is, and whether our reaction to it be comic or serious), ethnology, and The Golden Bough have concurred to make possible what was impossible even a few years ago. Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method. It is, I seriously believe, a step toward making the modern world possible for art.Eliot's skepticism about psychology aside, this is a pretty succinct expression of how myth became central to modernism.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: An Experiment in Self-Revelation

|

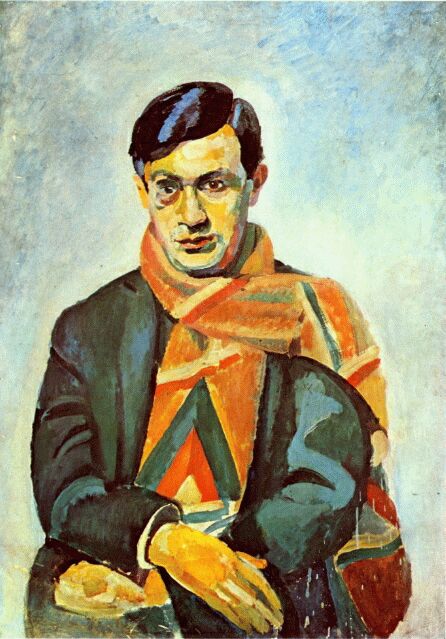

| Maurice Quentin de la Tour, Portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1753 |

The introduction to this section of the anthology, "Self-Consciousness," points out that the preoccupation with "self" stems from the "exploration of the unconscious mind and of the heritage of myth." It is "part of a larger concern with the distinctive qualities and value of subjective life."

Subjective life at its most intense is personal and private, wholly individual, and the value of subjective reality in this sense is a modern article of faith. The individual person has turned round upon himself, seeking to know all that he is and to unify all that he knows himself to be. The totality of the self has become the object of an inner quest. This cultivation of self-consciousness -- uneasy, ardent introspection -- often amounts to an almost religious enterprise. A first principle of self-consciousness is that nothing, however inglorious or unpleasant, should be ignored.And Rousseau claims that he has attempted in the Confessions not to ignore the "inglorious or unpleasant." He even assures the reader that he is "laying myself sufficiently open to human malice by telling my story, without rendering myself more vulnerable by any silence," and that if the reader suspects from "the slightest gap in my story, the smallest hiatus," that he is "refusing to tell the whole truth," that reader is mistaken both about Rousseau's candor and the nature of his enterprise.

The story that he tells about stealing a trifle, "a little pink and silver ribbon," and then blaming it on an innocent cook who, he assumes, lost her job -- "I do not know what happened to the victim of my calumny" -- may strike us as an insufficient objective correlative for the pangs of guilt that he claims to have experienced: "This cruel memory troubles me at times and so disturbs me that in my sleepless hours I see this poor girl coming to reproach me for my crime, as if I had committed it only yesterday." It seems less like a "confession" than like a moral fable, when Rousseau tells us, "So long as I have lived in peace it has tortured me less, but in the midst of a stormy life it deprives me of that sweet consolation which the innocent feel under persecution." He even reduces it to an epigram: "remorse sleeps while fate is kind but grows sharp in adversity."

But what makes the episode so remarkable in its context is the amount of analysis that Rousseau lavishes on it, examining minutely his motives -- or lack of them -- and the psychological drives that impelled him: "It was my shame that made me impudent, and the more wickedly I behaved the bolder my fear of confession made me." He is also able to transfer blame: "If M. de la Roque had taken me aside and said: 'Do not ruin that poor girl. If you are guilty tell me so,' I should immediately have thrown myself at his feet, I am perfectly sure. But all they did was to frighten me, when what I needed was encouragement."

Self-analysis leads Rousseau to generalizations about his personal failings:

In me are united two almost irreconcilable characteristics, though in what way I cannot imagine. I have a passionate temperament and lively and headstrong emotions. Yet my thoughts arise slowly and confusedly, and are never ready till too late. It is as if my heart and my brain did not belong to the same person. Feelings come quicker than lightning and fill my soul, but they bring me no illumination; they burn me and dazzle me. I feel everything and I see nothing; I am excited but stupid; if I want to think I must be cool.Rousseau is positing a norm here: the man who can unite passion with intellect. And he finds himself wanting. "If I had known in the past how to wait and then put down in all their beauty the scenes that painted themselves in my imagination, few authors would have surpassed me." This kind of self-analysis inevitably leads to a perception of one's own failings, and not of one's strength: "I have studied men, and I think I am a fairly good observer. But all the same I do not know how to see what is before my eyes; I can only see clearly in retrospect, it is only in my memories that my mind can work." After recounting a social faux pas, he sums up, "I think that I have sufficiently explained why, though I am not a fool, I am very often taken for one, even by people in a good position to judge."

And so there is another function of the Confessions: self-defense.

There is a certain sequence of impressions and ideas which modify those that follow them, and it is necessary to know the original set before passing any judgements. I endeavour in all cases to explain the prime causes, in order to convey the interrelation of results. I should like in some way to make my soul transparent to the reader's eye, and for that purpose I am trying to present it from all points of view, to show it in all lights, and to contrive that none of its movements shall escape his notice, so that he may judge for himself of the principle which has produced them.He admits that the Confessions may even be faulty as to fact -- "memories of middle age are always less sharp than those of early youth" -- but dismisses this as irrelevant: "I easily forget my misfortunes, but I cannot forget my faults, and still less my genuine feelings.... I cannot go wrong about what I have felt, or about what my feelings have led me to do." And he constantly insists on making the reader aware of what he is up to: "I warn those who intend to begin this book ... that nothing will save them from progressive boredom except the desire to complete their knowledge of a man, and a genuine love of truth and justice." The Confessions are self-revelation for the purpose of educating the reader as to the nature of a particular human character, and by extension, of the characteristics Rousseau shares with all human beings.

Above all, Rousseau prides himself on honesty:

I had always been amused at Montaigne's false ingenuousness, and at his pretence of confession his faults while taking good care only to admit to likeable ones; whereas I, who believe, and always have believed, that I am on the whole the best of men, felt that there is no human heart, however pure, that does not conceal some odious vice.