The Unconscious: The Freudian Unconscious (Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann); Liberation of the Unconscious (D.H. Lawrence, Tristan Tzara, André Breton)

The Unconscious: The Freudian Unconscious (Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann); Liberation of the Unconscious (D.H. Lawrence, Tristan Tzara, André Breton)_____

Sigmund Freud: The Origins of Culture

In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), Freud extended his theories of the unconscious from the individual to civilization itself, not without stretching a point or a few. Asserting that "we cannot fail to be struck by the similarity between the process of civilization and the libidinal development of the individual," he finds that sublimation of instinct both gives rise to civilization -- "it is what makes it possible for higher psychical activities, scientific, artistic, or ideological, to play such an important part in civilized life" -- and makes civilized humans more neurotic.

It is impossible to overlook the extent to which civilization is built up upon a renunciation of instinct, how much it presupposes precisely the non-satisfaction (by suppression, repression or other means?) of powerful instincts. This "cultural frustration" dominates the large field of social relationships between human beings. As we already know, it is the cause of the hostility against which all civilizations have to struggle.He posits that civilization arose because the constant "need for genital satisfaction" led to the cohabitation of males and females and thence to the family: “the male acquired a motive for keeping the female, or, speaking more generally, his sexual objects, near him; while the female, who did not want to be separated from her helpless young, was obliged, in their interests, to remain with the stronger male.” Greater combinations of peoples eventually followed all “in the service of Eros.” So civilization demonstrates “the struggle between Eros and Death, between the instinct of life and the instinct of destruction, as it works itself out in the human species.”

Of course, the community has to find ways of dealing with aggression, so it causes it to be redirected into the individual. “Civilization ... obtains mastery over the individual's dangerous desire for aggression by weakening and disarming it and by setting up an agency with him to watch over it, like a garrison in a conquered city.” It reinforces the superego and with it the sense of guilt.

And when Freud says guilt, he immediately thinks of the Oedipus complex. He posits that “the human sense of guilt goes back to the killing of the primal father, the remorse for which “was the result of the primordial ambivalence of feeling towards the father. His sons hated him, but they loved him, too.”

Now, I think, we can at last grasp two things perfectly clearly: the part played by love in the origin of conscience and the fatal inevitability of the sense of guilt. Whether one has killed one's father or has abstained from doing so is not really the decisive thing. One is bound to feel guilty in either case, for the sense of guilt is an expression of the conflict due to ambivalence, of the eternal struggle between Eros and the instinct of destruction or death.It's the primordial Catch-22.

Civilization, then, can only thrive “through an ever-increasing reinforcement of the sense of guilt, which will perhaps reach heights that the individual finds hard to tolerate.... The price we pay for our advance in civilization is a loss of happiness through the heightening of the sense of guilt.”

Thomas Mann: The Significance of Freud

|

| Thomas Mann in 1937 |

This address, “Freud and the Future,” was delivered in Vienna in 1936 on the occasion of Freud's eightieth birthday. It lauds him as “a great scientist,” which is not a characterization that everyone would agree with today, but more particularly because of Freud's influence on “the world of creative literature,” which is still undeniable.

Mann observes that Freud “did not know Nietzsche” or Novalis, Kierkegaard, or Schopenhauer, but that he seems to have intuited their ideas and given them practical application:

Freud's theories, Mann observes, have “penetrated into every field of science and every domain of the intellect: literature, the history of art, religion and prehistory; mythology, folklore, pedagogy, and what not.” The particular connection between psychoanalysis and literature that Mann observes “consists first in a love of truth, in a sense of truth, a sensitiveness and receptivity for truth's sweet and bitter, which largely expresses itself in a psychological excitation, a clarity of vision, to such an extent that the conception of truth actually almost coincides with that of psychological perception and recognition.”By his unaided effort, without knowledge of any previous intuitive achievement, he had methodically to follow out the line of his own researches; the driving force of his activity was probably increased by this very freedom from special advantage.

Again, Mann touches on the political horrors of his day in his discussion of the id, which “can take the upper hand with the ego, with a whole mass-ego, thanks to a moral devastation which is produced by the worship of the unconscious, the glorification of its dynamic as the only life-promoting force, the systematic glorification of the primitive and irrational. For the unconscious, the id, is primitive and irrational, is pure dynamic. It knows no values, no good or evil, no morality.” But he holds out hope “that the resolution of our great fear and our great hate, their conversion into a different relation to the unconscious ... may one day be due to the healing of this very science” -- i.e., psychoanalysis. “The free folk are the people of a future freed from fear and hate, and ripe for peace.”

Freud had a dirty mind, Lawrence asserts in this excerpt from Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious (1921), so Lawrence sets out to discover "the pristine unconscious in man." Freud's unconscious "is the cellar in which the mind keeps its own bastard spawn. The true unconscious is the well-head, the fountain of real motivity." Bad stuff happens when you hook your passions to the ideal instead of listening to the unconscious:

This motivizing of the passional sphere from the ideal is the final peril of human consciousness. It is the death of all spontaneous, creative life, and the substituting of the mechanical principle.In Freud, Lawrence claims, idealism and materialism, supposed philosophical opposites, unite: "the ideal becomes a mechanical principle," a kind of ghost in the machine. By identifying love as sex, Lawrence thinks, Freud sanctions all of its manifestations as physical: "incest is the logical conclusion of our ideals, when these ideals have to be carried into passional effect. And idealism has no escape from logic."

The "true unconscious," Lawrence asserts, "is the spontaneous life-motive in every organism." This life-motive begins "where the individual begins," at "the moment of conception." (Lawrence would almost certainly be a pro-lifer of some sort.)

By the unconscious we wish to indicate that essential unique nature of every individual creature, which is, by its very nature, unanalysable, undefinable, inconceivable. It cannot be conceived, it can only be experienced, in every single instance. And being inconceivable, we will call it the unconscious. As a matter of fact soul would be a better word. By the unconscious we do mean the soul.But not, he hastens to add, the soul as imagined by idealism, which has been reduced "that which a man conceives himself to be," so he returns to the word "unconscious."

Lawrence's unconscious is not, unlike Freud's, susceptible to the reductionism of science, which would reduce the sun to "some theory of burning gases, some cause-and-effect nonsense." We apprehend the sun imaginatively, not scientifically: "And even if we do have a mental conception of the sun as a sphere of blazing gas -- which it certainly isn't -- we are just as far from knowing what blaze is. Knowledge is always a matter of whole experience, what St. Paul calls knowing in full, and never a matter of mental conception merely."

Lawrence now goes off into his own psycho-physiological theories, which involve the solar plexus and the diaphragm and separate "planes" of the body. It's a personal myth that he compares to the concepts of the Greeks: "When the ancients located the first seat of consciousness in the heart, they were neither misguided nor playing with metaphor." What he is aiming at is a theory of unification. "The individual psyche divided against itself divides the world against itself, and an unthinkable process of calamity ensues unless there be a reconciliation."

Tristan Tzara: Dadaism

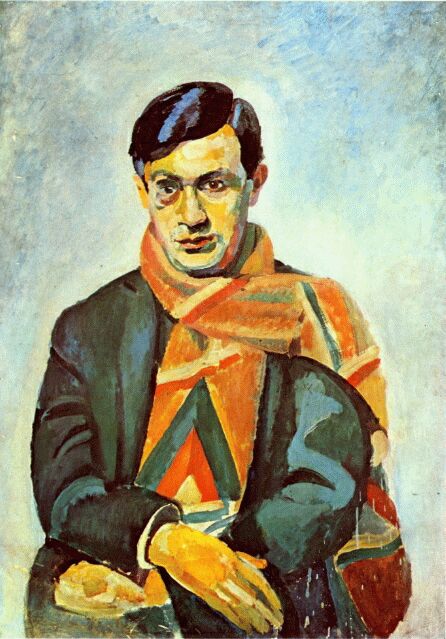

|

| Robert Delaunay, Portrait of Tristan Tzara, 1923 |

Dada rejects "explanations":

You explain to me why you exist. You haven't the faintest idea. You will say: I exist to make my children happy. But in your hearts you know that isn't so. You will say: I exist because God wills. That's a fairy tale for children. You will never be able to tell me why you exist but you will always be ready to maintain a serious attitude about life. You will never understand that life is a pun, for you will never be alone enough to reject hatred, judgments, all these things that require such an effort, in favor of a calm, level state of mind that makes everything equal and without importance.And yes, Tzara recognizes that there is an element of Buddhist detachment to that attitude.

Dadaism is anti-intellectual: "Intelligence is the triumph of sound education and pragmatism. Fortunately life is something else and its pleasures are innumerable." Dadaism sees itself as above all, life-affirming: "It is diversity that makes life interesting. There is no common basis in men's minds. The unconscious is inexhaustible and uncontrollable. Its force surpasses us." Moreover, art is inferior to life: "Art is not the most precious manifestation of life. Art has not the celestial and universal value that people like to attribute to it. Lie is far more interesting."

Tzara rejects idealism:

The Beautiful and True in art do not exist; what interests me is the intensity of a personality transposed directly, clearly into the work; the man and his vitality; the angle from which he regards the elements and in what manner he knows how to gather sensation, emotion, into a lacework of words and sentiments.The origins of Dada are in disgust, Tzara says. Disgust with the useless explanations of metaphysics, the pretentiousness of artists, "the false prophets who are nothing but a front for the interests of money," and so on. Dada is, in short, the first step toward postmodernism.

André Breton: Surrealism

|

| André Breton in 1924 |

Breton claims to find surrealist elements in Dante and Shakespeare and lists a number of precursors and contemporaries, including Jonathan Swift ("surrealist in malice"), Charles Baudelaire ("surrealist in morals"), Lewis Carroll ("surrealist in nonsense"), Georges Seurat ("surrealist in design") and Pablo Picasso ("surrealist in cubism"). Surrealism is not subject "to processes of filtering"; instead, surrealists are "content to be silent receptacles of so many echoes, modest registering machines that are not hypnotized by the pattern that they trace," and therefore "we are perhaps serving a yet much noble cause."

He gives Freud credit for awakening interest in and awareness of the processes of the unconscious, "an aspect of mental life -- to my belief by far the most important -- with which it was supposed that we no longer had any concern." Hence, "The imagination is perhaps on the point of reclaiming its rights." Freud's greatest achievement was that he gave scientific credibility and utility to the imaginative life and its reflection in art.

The Manfesto of Surrealism has improved on the Rimbaud principle that the poet must turn seer. Man in general is going to be summoned to manifest through life those new sentiments which the gift of vision will so suddenly have placed within his reach.Surrealism is a way of "securing expression in all its purity and force." It places surreality on the same plane as reality, "neither superior not exterior to it."

Breton acknowledges that Dadaism, as enunciated by Tzara, "although claiming until 1930 no connection with surrealism, is in perfect accord with" it. Indeed, surrealism, as Breton sees it, can claim kin to "several thought-movements." But unlike Tzara, Breton has "social action" in mind: "we hold the liberation of man to be the sine qua non of the liberation of the mind, and we can expect this liberation of man to result only from the proletarian Revolution." Surrealism, he says, "undertakes particularly the critical investigation of the notions of reality and unreality, of reason and unreason, of reflection and fimpulse, of knowing and 'fatal' ignorance, of utility and uselessness" -- it is consequently, like "Historical Materialism,' dialectical in nature.

I really cannot see, pace a few muddle-headed revolutionaries, why we should abstain from taking up the problems of love, of dreaming, of madness, of art and of religion, so long as we consider these problems from the same angle as they, and we too, consider Revolution.But the "muddle-headed revolutionaries" succeeded in kicking Breton out of the Communist Party.

Breton is most sanguine about the influence of surrealism on literature:

The hordes of words which were literally unleashed and to which Dada and surrealism deliberately opened their doors, ... will penetrate, at leisure, but certainly, the idiotic little towns of that literature which is still taught and, easily failing to distinguish between low and lofty quarterings, they will capture a fine number of turrets.... There is a pretence that it has not been noticed how much the logical mechanism of the sentence is proving more and more impotent by itself to give man the emotive shock which really gives some value to his life.Surrealism, Breton says, is the "excessively prehensile tail" of Romanticism.

He's not uncritical of some of the published pieces of surrealist "automatic writing": "The presence of in these items of an evident pattern has ... greatly hampered the species of conversion we had hoped to bring about through them." Such writing has to be "as much as possible detracted from the will to express" and "lightened of ideas of responsibility." If so, "they allow of a general reclassification of lyrical values" and "offer a key to go on opening indefinitely that box of never-ending drawers which is called man." The aim is not "to produce works of art, but to light up the unrevealed and yet revealable part of our being in which all the beauty, all the love and all the virtue with which we scarcely credit ourselves are shining intensely."

In short, surrealism will put an end to "the provoking insanities of 'realism'."

No comments:

Post a Comment