Chapter 7: The Serpent's Skin

Modigliani had plenty of friends in those early years in Paris. What he didn't have was a dealer or any sales on his own. And when Paul Alexandre left for Vienna in early 1909 to do research in his medical specialty, dermatology, Modigliani was left for a while without someone to watch over him. Alexandre asked his brother Jean to assume the task, "But Jean lacked his brother's rueful awareness that with Modigliani, whatever could go wrong, would." Jean saw him often, accompanying him to exhibitions, and even tried to find a paying job for him with a weekly magazine that published satirical caricatures of politicians, but the prospect of that kind of work appalled the artist.

And like Paul, Jean commissioned portraits from Modigliani, including one of himself and another of his girlfriend, the Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jean Alexandre, 1909 (Source) |

|

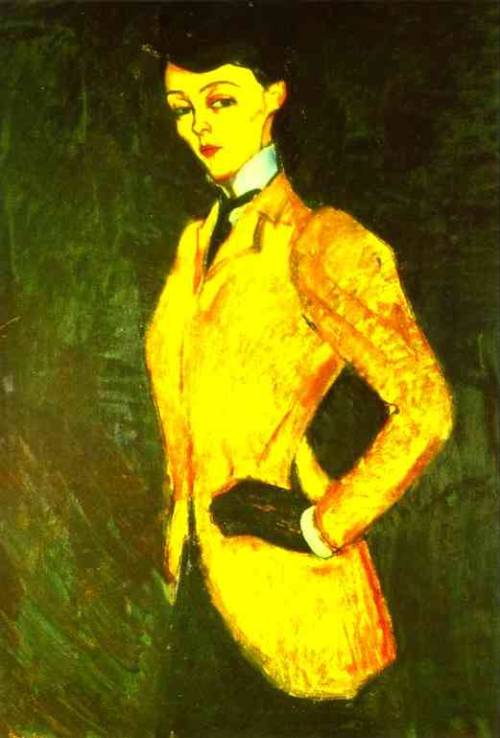

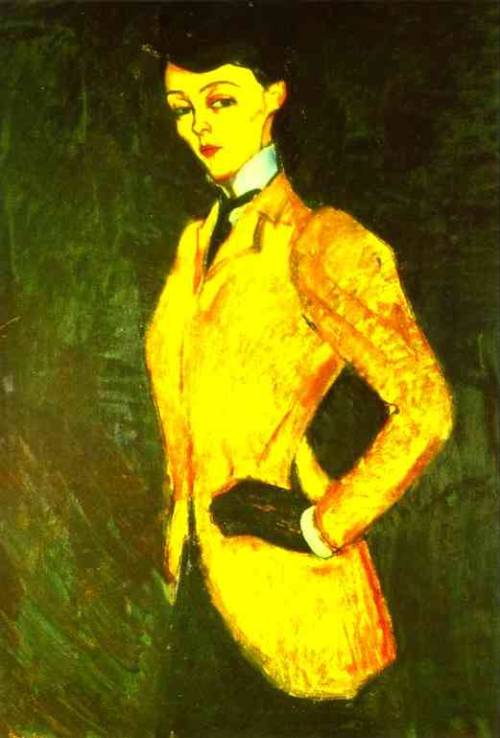

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of a Woman in a Yellow Jacket (The Amazon), 1909 (Source) |

Although Modigliani struggled with the portrait [of Jean] the implication, from Jean Alexandre's letters, is that the one of Marguerite, The Amazon, gave him even more trouble.... The sitter, obliged to pose for hours ... was becoming mutinous.... She finally gave Modi an ultimatum. She was leaving in a week's time and he had to finish. So he complied. The resulting portrait of her, hand on hip, has bold conviction but is not sympathetic. Perhaps the artist saw her as men of his age would have done, that is, too independent minded for comfort.

Modigliani also painted another of Paul Alexandre's circle, Maurice Drouard.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Maurice Drouard, 1909. Secrest: "His compelling study in blacks and strong background blues heightens the effect of Drouard's almost hypnotically blue-eyed stare." (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Joseph Levi, 1910. Secrest: "Levi, a painter and picture restorer in Montmartre ... often lent Modigliani money, and the artist reciprocated with a forceful portrait of almost tactile strength and immediacy, in slashes of scarlet, ocher, and black. The blunt brushstrokes suggest a brief experiment with Fauvism, probably after a close study of Matisse and Derain." (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, The Beggar of Leghorn, 1909. Secrest: "The influence of ... Cézanne [can be seen] in The Beggar of Leghorn. The unpromising subject has been transformed by a virtuoso display of color: high blues and grayed-off greens." (Source) |

|

|

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Beggar Woman, 1909. Secrest: "Perhaps the most fully realized of his portraits at this period is Beggar Woman, an example of the 'cool purposefulness' and economy of means that Modigliani was beginning to display. The lowere eyes, droop of the head, and particular set of the mouth speak volumes about the misery and pride of this anonymous daughter of the people." (Source) |

Paul Alexandre decided to cut his stay in Vienna short after only three months. About this time, Modigliani began to develop an interest in African art, a fascination he shared with Picasso and Matisse. He also went with Paul Alexandre to an exhibition of sculpture from Angkor Wat at the Trocadéro. Alexandre wrote that Modigliani found in primitive sculpture a simplicity and purity, "a search for the irreducible organic form. He also examined the collection of African sculpture owned by Frank Burty Haviland, a friend of Picasso's. "The masklike heads with their locked expressions were silent witnesses to Modigliani's most secret concerns, the mysteries of life, death, and rebirth.

He began to devote himself to sculpture, starting with sketches and then trying to recreate the image in stone that he hauled from building sites in a wheelbarrow.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Woman's Head, 1912 (Source) |

Almost all of the twenty or so known sculptures are carved in a limestone known as "Pierre d'Euville," quarried near a small town in eastern France, which is softer and easier to carve than marble. A few were in wood, also scavenged (or so it is said) from the railroad ties being stockpiled for a nearby Métro station at Barbes-Rochechouart. And almost all are heads.... Given Modigliani's chronic dissatisfaction with his work, the fact that he was constantly on the move and that sculptures are heavy, the wonder is that any survived.

He attracted attention from his fellow sculptors, including Jacques Lipchitz, who visited Modigliani in his studio and reported that "Modigliani, like some others at the time, was very taken with the notion that sculpture was sick, that it had become very sick with Rodin and his influence. There was too much modeling in clay, too much 'mud.' The only way to save sculpture was to start carving again, direct carving in stone." Jacob Epstein spent time with Modigliani looking for sheds where they could do their work together in open air. Epstein remarked, "All Bohemian Paris knew him. His geniality and esprit were proverbial." His fellow artists "were the first to recognize that Modigliani was doing important work." Augustus John recalled that he was so affected by Modigliani's heads that he kept seeing people in the street who resembled them.

Modigliani made several trips back to Livorno during this time, though the family was becoming impatient with the burden he placed on their finances. One acquaintance recalled that Emanuele said of his brother, "He's a drunkard and his drawings make me laugh." While in Livorno, he continued to work on his sculptures, and one acquaintance said that when some of Modigliani's boyhood friends made fun of "a stone head with a long nose," Modigliani tossed it into a canal. Others said that he dumped a wheelbarrow full of them in the canal. "The accounts varied, but the point of the story was how ridiculous the work was and how its creator had been shamed into destroying it."

Even while he was sculpting, Modigliani continued to paint, and one canvas in particular attracted attention when it was included in the Salon des Indépendants in 1910.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, The Cellist, 1909. Secrest: "Some powerful preparatory sketches ... show that the composition was diagonal from an early stage, the details simplified to their essences, an idea which continues to the finished work, which Modigliani painted in two slightly different versions. The artist's focus is on the communion of artist with his instrument, and the background, the addition of a fireplace, mirror, wallpaper, and bed, is subordinate.... The influence of Cézanne is clear enough, but ... it is an influence more transmuted than direct and already on the wane." (Source) |

Modigliani exhibited five other paintings, including

The Beggar of Leghorn and

Beggar Woman, at that salon, but sold nothing.

In the spring of 1910, Modigliani met the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. They were fascinated with each other, Akhmatova commenting that "all that was divine in Modigliani only sparkled through a sort of gloom." When they met, she was on her honeymoon, but her husband, the poet Nicolay Gumilyov, spent a lot of time at lectures and conferences, leaving her on her own with Modigliani. When she returned in the summer of 1911 they were together constantly. They would meet in the Luxembourg Gardens, and talk of poetry. "Modigliani loved Laforge, Mallarmé, and Baudelaire and would recite them by the hour, although not Dante, she thought out of consideration for her, since she knew no Italian." He was enthusiastic about Cubism, though he didn't attempt the style himself, and they went to the Department of Egyptian Antiquities in the Louvre, after which he drew her as an Egyptian queen. "He drew her repeatedly. At one time she owned sixteen of his drawings.... They were lost when [her] house was ransacked during the Russian Revolution."

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Sketch of Anna Akhmatova, 1911 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Sketch of Anna Akhmatova, 1911 (Source) |

Akhmatova returned to Russia after two months in Paris; they never met again.

For two or three years, from 1911 through 1913, Modigliani concentrated on a series of drawings, watercolors, and oils that depicted female figures. They are known as the caryatids.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, tempera and pencil, c. 1913 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, pastel, 1911 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, pencil, c. 1912 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, watercolor, pencil, 1913 (Source) |

|

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, oil, c. 1912 (Source) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, tempera, pencil, c. 1913 (Source) |

The figures seem to be designed to hold something up. "The woman as prop and buttress: this was now Modigliani's repetitive image, now standing, now crouching, now bent under the weight or lightly poised beneath it." He and Constantin Brancusi were working together now, and both were designing temples. Brancusi was actually commissioned by an Indian maharajah to create one in the 1930s, but it was never built.

Modigliani may have influenced Brancusi in another way:

As early as 1911 Modigliani was using a curious motif, a column decorated with geometric designs, seen in a portrait of Paul Alexandre. A symbol of the quest for the infinite, the Endless Column is an idea Brancusi took up six or seven years later. In his work it became a sculptural Tree of Life, the pillar supporting the firmament and the axis mundi on which the world turned.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paul Alexandre, c. 1912 (Source) |

|

| Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column, 1938 |

No comments:

Post a Comment