Nature: Organicism (Rainer Maria Rilke, Marcel Proust, André Gide, D.H. Lawrence)

Nature: Organicism (Rainer Maria Rilke, Marcel Proust, André Gide, D.H. Lawrence)_____

Rainer Maria Rilke: Nature, Man, and Art

I have to admit relief at turning from philosophers like Schopenhauer and Whitehead to poet and novelists, even though Rilke can present his own problems. This 1903 essay deals with the attempt of human beings to reconcile themselves through art to the manifest gulf between humanity and nature. In the statement, "It always seems that Nature does not know at all that we cultivate her and timidly put a small part of her forces to our own use," Rilke acknowledges not only the separation but also the implicit superiority of Nature. For "whatever men may have achieved, no man has been great enough to cause her to sympathize with his pain, to share in his rejoicing."

Like Robbe-Grillet, Rilke acknowledges the "pathetic fallacy," but unlike him, he is not ready to embrace the separation as the impetus to a new art. There are those who are

unwilling to leave the Nature they have lost, [who] go in pursuit of her and try now, consciously and by the use of their concentrated will, to come as near to her again as they were in their childhood without knowing it. It will be understood that [these people] are artists: poets or painters, composers or architects, fundamentally lonely spirits, who, in turning to Nature, put the eternal above the transitory, that which is most profoundly based on law above that which is fundamentally ephemeral, and who, since they cannot persuade nature to concern herself with them, see their task to be the understanding of Nature, so that they may take their place somewhere in her great design.Rilke sees this attempt at a reunion with Nature as "the theme and purpose of all art," that is, "the reconciliation of the Individual and the All, and the moment of exaltation, the artistically important Moment, would seem to be that in which the two scales of the balance counterpoise one another." Thus, "a symphony mingles the voices of a stormy day with the tumult of our blood" and "a building owes its character half to us and half to the forest."

Marcel Proust: The Life of the Hawthorn

|

| Marcel Proust, date unknown |

In this rhapsodic selection from Swann's Way, Proust recounts the narrator's boyhood experience contemplating the beauty of hawthorn blossoms. In the context of the novel, it links up with his first encounter with Gilberte, Swann's daughter, the object of endless fascination throughout much of In Search of Lost Time. It also serves to introduce the narrator's passionate desire to establish some sort of intimacy with nature, "to absorb myself in the rhythm which disposed their flowers here and there with the light-heartedness of youth, and at intervals as unexpected as certain intervals of music ... like those melodies which one can play over a hundred times in succession without coming any nearer to their secret." Music once again becomes the touchstone for the aesthetic experience. But he is doomed to failure:

In this rhapsodic selection from Swann's Way, Proust recounts the narrator's boyhood experience contemplating the beauty of hawthorn blossoms. In the context of the novel, it links up with his first encounter with Gilberte, Swann's daughter, the object of endless fascination throughout much of In Search of Lost Time. It also serves to introduce the narrator's passionate desire to establish some sort of intimacy with nature, "to absorb myself in the rhythm which disposed their flowers here and there with the light-heartedness of youth, and at intervals as unexpected as certain intervals of music ... like those melodies which one can play over a hundred times in succession without coming any nearer to their secret." Music once again becomes the touchstone for the aesthetic experience. But he is doomed to failure: the sentiment which they aroused in me remained obscure and vague, struggling and failing to free itself, to float across and become one with the flowers. They themselves offered me no enlightenment, and I could not call upon any other flowers to satisfy this mysterious longing.

Elsewhere in the Search we will learn that only through "involuntary memory," an experience triggered unbidden by a sound, a tactile sensation, or, most famously, the taste of a madeleine dipped in lime-flower tea, can contact with the world outside the self offer the enlightenment the narrator seeks here.

It's also significant that this is a childhood experience of the narrator's, an impression made on the unsophisticated mind. The narrator's grandfather directs his attention to a spectacular pink hawthorn, which makes him think of crushed strawberries mixed in cream cheese:

And these flowers had chose precisely the colour of some edible and delicious thing, or of some exquisite addition to one's costume for a great festival, which colours, inasmuch as they make plain the reason for their superiority, are those whose beauty is most evident to the eyes of children, and for that reason must always seem more vivid and more natural than any other tints, even after the child's mind has realised that they offer no gratification to the appetite, and have not been selected by the dressmaker.

He ascribes their beauty to Nature's attempt to charm: "And indeed, I had felt at once, as I had felt before the white blossom, but now still more marvelling, that it was in no artificial manner, by no device of human construction, that the festal intention of these flowers was revealed, but that it was Nature herself who had spontaneously expressed it."

André Gide: Natural Joy

In 1935, when Gide was involved in a flirtation with communism (which would end when he actually visited the Soviet Union), he wrote Later Fruits of the Earth, an addendum of sorts to the original Fruits of the Earth, published forty years earlier. These excerpts capture him in an affirmative mood tempered by realizations of human limitations. "All nature ... teaches that man is born for happiness. It is the effort after pleasure that makes the plant germinate, fills the hive with honey, and the human heart with love." It's worth remembering Schopenhauer's assertion that pleasure is a bodily manifestation of will, and that will is, among other things, "the force which germinates and vegetates in the plant."

But in order to achieve the happiness he seeks, Gide wants to be freed from the past, to which he is "in bondage.... Not a gesture to-day but was determined by what I was yesterday. But I who am at this moment, I, instantaneous, fleeting, irreplaceable, I escape." Or he tries to, halted by fears of the future as well: "Consequence of our acts. Consequence with ourselves. Am I to expect nothing from myself but a sequel?" So he determines to throw caution to the winds: "Winds of the abyss, bear me away!"

He is also trammeled by the things of the world: "the important thing is that we should contemplate God with the clearest possible eyes, and I feel that every object on this earth that I covet becomes opaque by very reason of my coveting it, and that the whole world then loses its transparence ... so that God ceases to be perceptible to my soul, and by abandoning the Creator for the creature, my soul ceases to live in eternity and loses the kingdom of God." (As we see later, by "God" he means Nature.)

He returns to the original thought, that the pleasure principle is supreme: "With pleasure for a guide, all things aspire to greater thriving, to increased consciousness, to progress.... And this is why I have found more instruction in pleasure than in books; why I have found in books more obfuscation than light." Physical pleasure allows him to transcend himself: "the secret workings of carnal desire drove me out of myself towards an enchanting confusion." And paradoxically, "When I stopped looking for myself it was in love that I found myself again." His desires "alone were capable of instructing me. I yielded to them."

Contemplating the impossibility that a caterpillar should ever turn into something so radically different as a butterfly -- "not only does the shape change, but the habits, the appetites" -- provokes a realization about the trap in which one is caught by clinging too closely to one's identity. The pursuit of self-knowledge is a trap:

Know thyself. A maxim as pernicious as it is ugly. To observe oneself is to arrest one's development. The caterpillar that tried "to know itself" would never become a butterfly.

So nature becomes his divinity, "for simplicity's sake and because it irritates the theologians." Among the lessons to be learned from nature is "that everything that is young is tender ... and no growth is possible unless it bursts the sheathes in which at first it was swaddled." Humankind has failed to progress because it is wrapped in the past: "Comrade, you must refuse henceforth to seek your nourishment in the milk of tradition, man-distilled and man-filtered.... Look at the winged seeds of the plane or the sycamore flying off as if they understood that the paternal shade can offer them nothing but a dwindling and atrophied existence."

Understand rightly the Greek fable. It teaches us that Achilles was invulnerable except in that spot of his body which had been made soft by the remembrance of his mother's touch.

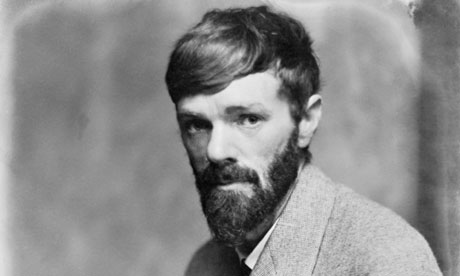

D.H. Lawrence: The Death of Pan

|

| D.H. Lawrence, c. 1920 |

Like Gide, Lawrence is not quite ready to accept the death of Pan, except insofar as it becomes a metaphor for the detachment of human beings from nature.

Gradually men moved into cities. And they loved the display of people better than the display of a tree. They liked the glory they got of overpowering one another in war. And, above all, they loved the vainglory of their own words, the pomp of argument and the vanity of ideas.Pan survives, however, in poetic pantheists such as Wordsworth and Whitman, but Lawrence dismisses this as trifling. "All Walt is Pan, but not all Pan is Walt."

We still pretend to believe that there is One mysterious Something-or-other back of Everything, ordaining all things for the ultimate good of humanity. It wasn't back of the Germans in 1914, of course, and whether it's back of the bolshevists is still a grave question. But still, it's back of us, so that's all right.But this is all make-believe, Lawrence insists. "In the days before man got too much separated from the universe, he was Pan, along with all the rest."

Still, Lawrence senses the presence of Pan in trees, such as the big pine on the ranch where he lived in New Mexico. He admires the tree as a "magnificent assertion" -- a phallic one -- and says that he has "become conscious of the tree, and of its interpenetration into my life.... I am conscious that it helps to change me, vitally. I am even conscious that shivers of energy cross my living plasm, from the tree, and I become a degree more like unto the tree, more bristling and turpentiney, in Pan." But then he distances himself from these assertions, keying into the reader's own resistance to such nature-worship:

Of course, if I like to cut myself off, and say it is all bunk, a tree is merely so much lumber not yet sawn, then in a great measure I shall be cut off. So much depends on one's attitude. One can shut many, many doors of receptivity in oneself; or one can open many doors that are shut.And therein lies Lawrence's point, which is very much the point that Wallace Stevens, among others, made: One can choose to engage the imagination, to open the doors and participate in nature, or not. "So much depends on one's attitude," Lawrence puts it, and Lawrence is all about attitude:

Is it truer to life to insulate oneself from the influence of the tree's life, and to walk about in an inanimate forest of standing lumber, marketable in St. Louis, Mo.? Or is it truer to life to know, with a pantheistic sensuality, that the tree has its own life, its own assertive existence, its own living relatedness to me: that my life is added to, or militated against, by the tree's life?... What can a man do with his life but live it? And what does life consist in, save a vivid relatedness between the man and the living universe that surrounds him? Yet man insulates himself more and more into mechanism, and repudiates everything but the machine and the contrivance of which he himself is master, god in the machine.Pan's death came about not with the arrival of Christianity, Lawrence asserts, but with the scientific revolution, when human beings "discovered the 'idea.' He found that all things were related by certain laws. The moment man learned to abstract, he began to make engines that would do the work of his body." The power of abstraction, of the acceptance of a duality of mind and body, "was the death of the great Pan. The idea and the engine came between man and all things, like a death. The old connexion, the old Allness, was severed, and can never be ideally restored. Great Pan is dead."

So humans became what realists such as Zola, for example, advocated: masters of nature:

With all the mechanism of the human world, man is to a great extent master of all life, and of most phenomena.Lawrence then gives us a picture of primitive life, when man "lived in a ceaseless living relation to his surrounding universe." But just when one thinks that Lawrence is indulging in a sentimental primitivism, he throws some cold water on the scene: "It is useless to glorify the savage. For he will kill Pan with his own hands, for the sake of a motor-car.... And we cannot return to the primitive life, to live in tepees and hunt with bows and arrows." So although "The Pan relationship, which the world of man once had with all the world, was better than anything man has now," it can't be recovered. The best Lawrence has to offer is a recognition that "life itself consists in a live relatedness between man and his universe: sun, moon, stars, earth, trees, flowers, birds, animals, men, everything -- and not in a 'conquest' of anything by anything."

And what then? Once you have conquered a thing, you have lost it. Its real relation to you collapses.

A conquered world is no good to man. He sits stupefied with boredom upon his conquest.

No comments:

Post a Comment