Realism: Socialist Realism (Georg Lukács). A New Realism (Alain Robbe-Grillet).

Realism: Socialist Realism (Georg Lukács). A New Realism (Alain Robbe-Grillet)._____

Georg Lukács: Historical Truth in Fiction

In this excerpt from Studies in European Realism (1948), Lukács portrays Balzac, despite his Catholicism and monarchism, as a model realist, contrasting him with writers like James Joyce, who put more emphasis on the psychology of the individual than on the social context. Marxism, he asserts, points "the direction in which history moves forward," with a "well-defined philosophy of history [that] is based on a flexible and adaptable acceptance and analysis of historical development."

|

| Georg Lukács in 1952 |

Though Lukács's Marxism is forward-looking, he asserts that "the great Marxists were jealous guardians of our classical heritage in their aesthetics as well as in other spheres." Not because they wish to return to the past, he hastens to add, but because "the great Marxists look for the true highroad of history, the true direction of its development, the true course of the historical curve."

For the sphere of aesthetics this classical heritage consists in the great arts which depict man as a whole in the whole of society.... The ancient Greeks, Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, Balzac, Tolstoy all give adequate pictures of great periods of human development and at the same time serve as signposts in the ideological battle fought for the restoration of the unbroken human personality.Balzac becomes a "signpost," therefore, in the development of a realist aesthetic in the novel. But his supposed heirs, such as Flaubert and Zola, Lukács regards as deviations from the proper path. Balzac's heirs were "the Russian and Scandinavian writers of the second half of the century."

Lukács sees "literary fashions" as "swinging to and fro between the pseudo-objectivism of the naturalist school and the mirage-subjectivism of the psychologist or abstract-formalist school." Realism, he asserts, is "not some sort of middle way between false objectivity and false subjectivity, but on the contrary the true, solution-bringing third way." It "depicts man and society as complete entities, instead of showing merely one or the other of their aspects." He credits Balzac with seeing the problem clearly in his story "Le Chef-d'oeuvre inconnu," about a painter whose experiment "to create a new classic three-dimensionality by means of an ecstasy of emotion and colour" ends up with "a tangled chaos of colours out of which a perfectly modelled female leg and foot protrude as an almost fortuitous fragment." (Picasso loved the story so much he moved to the street in Paris that was its setting.)

"The central problem of realism is the adequate presentation of the complete human personality," Lukács says. But writers like Zola overemphasize "the physiological aspects of self-preservation and procreation," while others "sublimate man into purely mental, psychological processes." He argues that "any description of mere biological processes -- be these the sexual act or pain or sufferings, however detailed and from the literary point of view perfect it may be -- results in a levelling-down of the social, historical and moral being of men." The increased openness of literature to material that was once taboo -- i.e., sex and violence -- has become "an obstacle to such essential artistic expression as illuminating human conflicts in all their complexity and completeness." Similarly, the overemphasis on individual psychology, if detached from its "organic connection with social and historical factors ... distorts and impoverishes the portrayal of the complete human personality."

A description "in the Zola manner of, say, an act of copulation between Dido and Aeneas or Romeo and Juliet" would lack the "inexhaustible wealth of culture and human facts and types" that Virgil's and Shakespeare's account of these "erotic conflicts" presented to us. And Joyce's "shoreless torrent of associations" is equally incapable of creating "living human beings." Lukács cites the Swiss writer Gottfried Keller's statement, "Everything is politics," explaining that Keller meant, like Balzac and Tolstoy, that "every action, thought and emotion of human beings is inseparably bound up with the life and struggles of the community" and that the "division of the complete human personality into a public and a private sector was a mutilation of the essence of man."

He acknowledges that some will find it odd that he opposes Zola, "a writer of the left," and praises Balzac, whose "political creed was legitimist royalism." But Balzac, despite his political stance, "inexorably exposed the vices and weakness of royalist feudal France and described its death agony with magnificent poetic vigour." Engels cited Balzac's work as "the triumph of realism," and Lukács asserts, "It touches the essence of true realism: the great writer's thirst for truth."

A great realist such as Balzac, if the intrinsic artistic development of situations and characters he has created comes into conflict with his most cherished prejudices or even his most sacred convictions, will, without an instant's hesitation, set aside these his own prejudices and convictions and describe what he really sees, not what he would prefer to see.It is "second-raters," he says, "who nearly always succeed into bringing their own Weltanschauung into 'harmony' with reality.... No writer is a true realist -- or even a truly good writer, if he can direct the evolution of his own characters at will." Zola's failing was that "his epoch turned him into a mere observer and when at last he answered the call of life" -- presumably Lukács is referring to Zola's participation in the Dreyfuss case -- "it came too late to influence his development as a writer."

Lukács almost seems to believe that if he'd lived long enough, Balzac would have turned into a Marxist: "No one experienced more deeply than Balzac the torments which the transition to the capitalist system of production inflicted on every section of the people, the profound moral and spiritual degradation which necessarily accompanied this transformation on every level of society." He took what Lukács sees as a wrong turn into "Catholic legitimism ... tricked out with Utopian conceptions of English Toryism."

The real heirs of Balzacian realism, Lukács asserts, were found in Russia, and particularly in Tolstoy, but he blames "reactionaries" for limiting the familiarity of the rest of Europe with other Russian writers because the reactionaries "felt instinctively that Russian realism ... is an antidote to all reactionary infection." Tolstoy was even co-opted by the reactionaries who tried "to turn him into a mystic gazing into the past; into an 'aristocrat of the spirit' far removed from the struggles of the present."

The result was a myth of a "holy Russia" and Russian mysticism. Later, when the Russian people in 1917 fought and won the battle for liberation, a considerable section of the intelligentsia saw a contradiction between the new free Russia and the older Russian literature. One of the weapons of counter-revolutionary propaganda was the untrue allegation that the new Russia had effected a complete volte-face in every sphere of culture and had rejected, in fact was persecuting, older Russian literature.Dostoevsky, Lukács asserts, was also a victim of "reactionary criticism" that derived "the alleged spiritual and and artistic content of [his work] from certain [of his] reactionary views." But he holds up the development of Russia as an example of "the extent to which a great realist literature can fructifyingly educate the people and transform public opinion." (It's worth remembering that Lukács wrote these words at the outset of the Cold War, before the lines between East and West had fully hardened, and some Western intellectuals could still believe in "the new free Russia.")

He praises Tolstoy for sinking "his roots into the mass of the Russian peasantry, and Gorki of the industrial workers and landless peasants," and encourages writers to develop "an ardent love of the people, a deep hatred of the people's enemies and the people's own errors, the inexorable uncovering of truth and reality, together with an unshakable faith in the march of mankind and their own people towards a better future."

Alain Robbe-Grillet: Dehumanizing Nature

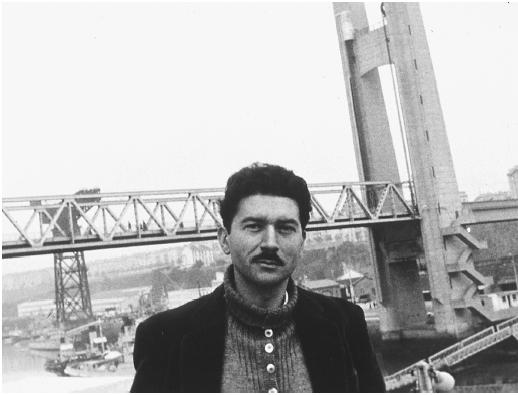

|

| Alain Robbe-Grillet, date unknown |

"The only conception of the novel in effect today remains ... that of Balzac," Robbe-Grillet asserts, with the result that "The art of the novel ... has achieved such a degree of stagnation ... that it is scarcely imaginable that it can survive for long without radical changes." He proposes that the change reflect our recognition of the separation between human beings and the world: "Around us, defying the mob of our animistic or protective adjectives, the things are there. Their surfaces are clear and smooth, intact, neither dubiously glittering, nor transparent. All our literature has not yet succeeded in penetrating their smallest corner, in softening their slightest curve." This deanimated nature as provoked us to imagine it as sharing in and symbolizing our emotional states. And as a result, the world in which we live essentially disappears, ceases to be itself, becomes only a surface onto which we project ourselves.

In the original novel, the objects and gestures forming the very tissue of the plot disappeared completely, leaving behind only their significations: the empty chair became only absence or expectation, the hand placed on a shoulder became a sign of friendliness, the bars on the window became only the impossibility of leaving.... But in the cinema, one sees the chair too, the movement of the hand, the shape of the bars. What they signify remains obvious, but, instead of monopolizing our attention, it becomes something added, even something in excess, because what touches us, what persists in our memory, what appears as essential and irreducible to vague intellectual concepts, are the gestures themselves, the objects, the movements, and the contours, to which the image has suddenly (and unintentionally) restores their reality.So Robbe-Grillet challenges the novelist to give us things in their own reality, "to construct a world both more solid and more immediate. Let it be first of all by their presence that objects and gestures impose themselves," and not have some extra meaning projected on them by "some system of reference, whether sentimental, sociological, Freudian, or metaphysical."

No longer will objects be mere the vague reflection of the hero's vague soul, the image of his torments, the mainstay of his desires. Or rather, if objects must still accept this tyranny, it will be only in appearance, only to show all the more clearly to what extent they remain independent and alien.He rejects the need to describe objects in "words of a visceral, analogical, incantatory character." Instead, the writer must learn to keep his distance and choose "the word that contents itself with measuring, locating, limiting, defining." In a passage of description titled "The Dressmaker's Dummy," Robbe-Grillet presents a setting, describing a coffee pot sitting on a table, a window, a dressmaker's dummy, and the mirror that reflects these things. It is purged of all emotional significance, but because of the precision with which Robbe-Grillet explores the scene, it comes to have an almost hallucinatory quality. Then, at the end, he notes that the coffee pot is sitting on a tile whose design "is an owl with two huge, almost frightening eyes. But, for the moment, nothing can be seen because of the coffee pot." Although he has introduced an emotion with the word "frightening," he doesn't ascribe the emotion to the image on the tile. In fact, as he notes, the image can't even be seen.

He recognizes that we tend to valorize "humanity" above all else: "If I say, 'The world is mankind,' I shall always obtain absolution; but if I say, 'Things are things, and man is only man,' I shall be immediately judged guilty of a crime against humanity. The crime is to state that something exists in the world which is not mankind, which makes no signs to man, which has nothing in common with him." We are in the habit of viewing the world through metaphor, which "is never an innocent figure of speech. To say that time is 'capricious' or a mountain 'majestic,' to speak of the 'heart' of the forest, of a 'pitiless' sun, of a village 'crouching' in the hollow of a valley is, to some extent, to furnish information about the things themselves: forms, dimensions, situations, etc." But it also imposes a moral character to the mountain and volition to the sun. "Metaphor, which is supposed to express only comparison without concealed meaning, always introduces in fact a subterranean communication, a movement of sympathy -- or of antipathy -- which is always its true raison d'être. As far as comparison is concerned, metaphor is nearly always useless, adding nothing new to the description."

The trouble with this habit of metaphor is that it leads to falsity. "Having acquired the habit, I would easily progress further. Once I accepted the principle of this communion [between humanity and external nature], I would speak of the sadness of a landscape, of the indifference of a stone, of the fatuousness of a coal bucket. These new metaphors furnish no appreciable additional information concerning the objects subjected to my scrutiny.

To confuse my own sadness with the sadness that I attribute to a landscape, to view this relationship as something more than superficial, is to admit, by the same token, that my present life is to a degree predestined; for this landscape existed before I came; if it really is sad, it was already sad prior to my arrival, and this rapport that I feel today between its form and my emotional state must have awaited me since before my birth -- this particular sadness was therefore always destined for me.Robbe-Grillet sees it as the writer's duty to "reject the 'pananthropic' idea contained in traditional (if not any other) Humanism."

"Man looks out at the world, and the world does not return his glance.... And modern (or future) man no longer feels this absence of meaning as a lack, or as an emotional distress.... For, by refusing communion, he also refuses tragedy." Robbe-Grillet's definition of tragedy is "an attempt to salvage, to 'recuperate' the separation between man and things, and to make of that distance a new value." We are expected to mourn the distance between humanity and the external: "Misery, failure, solitude, guilt, madness: such are the accidents of our existence that we are now expected to welcome as the best tokens of our salvation."

Wherever we find distance, separation, duality, or cleavage, we also find the possibility of experiencing these as suffering, with the subsequent elevation of such suffering to the status of a sublime necessity. Such pseudo-necessity is both a path towards a metaphysical 'beyond' and a door closed against any realistic future. If tragedy consoles us today, it also forbids all more solid conquests for tomorrow.... There is no longer any question of seeking a remedy for our misfortunes, once tragedy sets its sights upon making us love our ills.Robbe-Grillet's new kind of realism would have us accept the separation of man and nature and not use it as a crutch. He finds contemporary fiction overloaded with this kind of defeatist "tragic spirit," and cites "two great novels, in recent decades, [that] have presented us with two new forms of this fatal complicity, under the names of absurdity and nausea.... Albert Camus, everyone knows, has designated as absurdity the impassable abyss that stands between man and the world, between the aspirations of the human spirit and the incapacity of the world to satisfy them." But Robbe-Grillet finds that in L'Étranger, Camus continues to approach the external world through metaphor, for example, "the evening is 'like a melancholy truce." "Thus 'absurdity' turns out to be a form of tragic Humanism. It is not a recognition of the separation between man and objects. It is a lovers' quarrel between them, which leads to a crime of passion. The world is accused of complicity in murder.... Camus does not refuse anthropomorphism, [as Jean-Paul Sartre asserts,] but uses it with great economy and subtlety, in order to give it greater weight."

Similarly, in La Nausée, Sartre places us "once more in a wholly 'tragi-fied' universe, marked by fascination with disparity, by solidarity with things because they bear within themselves their own negation, by redemption (here, accession to self-awareness) through the very impossibility of reaching a true agreement. We find, that is, the ultimate salvaging of all separations, failures, solitudes and contradictions."

The impulse to anthropomorphize prevents humans from "seeing things," and instead restricts us "to feeling, in their name, entirely humanized impressions and desires.... in this universe peopled by things, things become nothing more than mirrors endlessly reflecting man's own image." So Robbe-Grillet proposes, "To describe things ... requires that we place ourselves deliberately outside, in front of, them. We must neither appropriate them to ourselves, nor transfer anything to them.... Science is the only honest means available to man for deriving advantage from the world around him. But this advantage is only material; however disinterested science may be, it is only justified by the eventual development of utilitarian techniques." Literature must attempt to "construct [the] exteriority and independence of objects," even to the extent of reducing them to geometrical shapes.

The most common complaints against such geometric information, that "it says nothing to the spirit," that "a photograph or a dimensioned sketch would give a better account of the form," etc., are strange objections indeed. Can anyone imagine that I had not thought of all that from the outset? Something entirely different is at issue.... To record the separation between an object and myself, the distances pertaining to the object itself (its exterior distances, that is, its measurements), and the distances between objects; to insist, further, on the fact that these are only distances (and not heartrending separations) -- all this amounts to taking for granted that things are "there" and that they are only things, each limited to itself. It is no longer a question of choosing between a happy agreement and an unhappy solidarity. Henceforth we refuse all complicity with objects.

|

| From Last Year at Marienbad. |

No comments:

Post a Comment