Realism: Historical Determinism (Honoré de Balzac, Hippolyte Taine, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy)

Realism: Historical Determinism (Honoré de Balzac, Hippolyte Taine, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy)_____

Honoré de Balzac: Society as Historical Organism

In the 1842 Preface in which he discusses the character of The Human Comedy, essentially the corpus of his fiction, Balzac observes that the animal man exhibits more intraspecies variety than the other animals, largely owing to the influence of society:

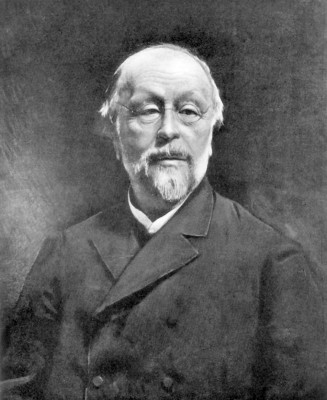

|

| Honoré de Balzac in 1842 |

The differences between a soldier, an artisan, a man of business, a lawyer, an idler, a student, a statesman, a merchant, a sailor, a poet, a beggar, a priest, are as great, though not so easy to define, as those between the wolf, the lion, the ass, the crow, the shark, the seal, the sheep, etc.Moreover, among the various human types, "the dress, the manners, the speech, the dwelling ... are absolutely unlike, and change with every phase of civilisation."

He credits Walter Scott with raising "to the dignity of the philosophy of History the literature which, from age to age, sets perennial gems in the poetic crown of every nation where letters are cultivated." But even Scott "never thought of connecting his compositions in such a way as to form a complete history of which each chapter was a novel, and each novel the picture of a period."

This is precisely Balzac's goal: to write a history of manners, though he downplays his part a bit. "French society would be the real author; I should only be the secretary." But as secretary he reserves the right to edit a bit, in line with his Catholic and monarchical beliefs. "Man is neither good nor bad; he is born with instincts and capabilities; society, far from depraving him, as Rousseau asserts, improves him, makes him better; but self-interest also develops his evil tendencies." So he comes down on the side of society, as long as it is the right kind of society: "Christianity created modern nationalities, and it will preserve them. Hence, no doubt, the necessity for the monarchical principle. Catholicism and Royalty are twin principles.... I write under the light of two eternal truths -- Religion and Monarchy."

Which of course does not mean that he lets his beliefs get in the way of telling the truth about fallible human beings, and consequently he gets in trouble for what he writes: "If you are truthful in your pictures; if by dint of daily and nightly toil you succeed in writing the most difficult language in the world, the word immoral is flung in your teeth. Socrates was immoral; Jesus Christ was immoral; they both were persecuted in the name of the society they overset or reformed." As a consequence of Balzac's honest portrayal of society as it is, "the critics at once raised the cry of immorality, without pointing out the morality of another portion intended to be a perfect contrast." And here Balzac claims his Catholicism as a strength, especially when it comes to portraying women: "In Protestantism there is no possible future for the woman who has sinned; while in the Catholic Church, the hope of forgiveness makes her sublime."

Hippolyte Taine: Art as Historical Product

|

| Hippolyte Taine, from a portrait by Léon Bonnat, date unknown |

True history begins when the historian has discerned beyond the mists of ages the living, active man, endowed with passions, furnished with habits, special in voice, feature, gesture, and costume, distinctive and complete, like anybody that you have just encountered in the street.It is a mistake to treat human beings out of the context of history: "the moral organization of a people or an age is as special and distinct as the physical structure of a family of plants or an order of animals."

Taine is big, therefore, on the idea of "national character." Germany he characterizes by "its genius, so pliant, so broad, so prompt in transformations, so fitted for the reproduction of the remotest and strangest states of human thought." England is "matter-of-fact" and "suited to grappling with moral problems, to making them clear by figures, weights, and measures, by geography and statistics, by texts and common sense." France gets credited with "unceasing analysis of characters and of works" and "ever ready irony at detecting weaknesses," products of "its Parisian culture and drawing-room habits," as well as with "skilled finesse in discriminating shades of thought."

But none of these glittering generalities quite prepares us for Taine's concept of race, and especially for its assertion that

the Aryan people, scattered from the Ganges to the Hebrides, established under all climates, ranged along every degree of civilization, transformed by thirty centuries of revolutions, shows nevertheless in its languages, in its religions, in its literatures, and in its philosophies, the community of blood and intellect which still to-day binds together all its offshoots.This is nineteenth-century racism in flower, though he modifies it by admitting environment to the mix, so that he can observe of "the history of Aryan nations" that there is a "profound difference ... between the Germanic races on the one hand, and the Hellenic and Latin races on the other." You get the sense of the theory growing more wobbly as he admits to subdivisions within "race," but the stereotyping persists. And then he adds the historical moment, the epoch, or the milieu to the mix, inviting us to compare the differences between "French tragedy under Corneille and under Voltaire, and Greek drama under Aeschylus and under Euripedes, Latin poetry under Lucretius and under Claudian, and Italian painting under Da Vinci and under Guido."

Few of us, except experts in the field, would be able to do that on our own, of course, but Taine is being theoretical here -- we can assume that there are significant differences between each of the "two moments," but his point is also that "the first work has determined the second. In this respect, it is with a people as with a plant; the same sap at the same temperature and in the same soil produces, at different stages of its successive elaborations, different developments, buds, flowers, fruits, and seeds, in such a way that the condition of the following is always that of the preceding and is born of its death."

And sometimes these "fundamental forces ... combine to neutralize each other," producing fallow periods for a nation's art. In Taine's view this happened in the seventeenth century when "the blunt, isolated genius of England awkwardly tried to don the new polish of urbanity." The result, he says, is "the literary incompleteness, the licentious plays, the abortive drama of Dryden and Wycherly." Others would value Dryden's All for Love and Wycherley's The Country Wife as anything but "abortive," and Taine's overlooking the poetry of their contemporary, John Milton, suggests that his tastes lay elsewhere. But he credits a more fortuitous combination of race, environment, and epoch with "painting in Flanders and Holland in the seventeenth century, ... poetry in England in the sixteenth century, [and] music in Germany in the eighteenth century."

Taine credits others with exploring these historical influences on art before him, including Montesquieu and Stendhal, who "was the first to point out fundamental causes such as nationalities, climates and temperaments," but their times were not ripe for a recognition of such theories. Taine is sure they are now, however, and that "among the documents which bring before our eyes the sentiments of preceding generations, a literature and especially a great literature, is incomparably the best.... It is mainly in studying literature that we are able to produce moral history, and arrive at some knowledge of the psychological laws on which events depend."

Gustave Flaubert: Shortcomings of Taine's Theory

A few words are sometimes the best, and in a letter to his frequent correspondent Edma Roger des Genettes, Flaubert expends very few asserting, "There is something more in Art than the surroundings in which it is produced and the psychological antecedents of the artist." Taine underestimates talent, and can't explain by his theory "the individuality, the specific quality which makes one what one is.... In the old days it was believed that literature was an entirely individual matter, and that books dropped like thunderbolts from the skies. Now we have come to deny all will and all absolutes. The truth, I think, lies in the middle." But that Flaubert was provoked to comment suggests how influential Taine was.

Leo Tolstoy: Man as the Creature of History

|

| Leo Tolstoy in the 1850s |

So searching for causality in history is futile: "Nothing is the cause." Instead there is only "the coincidence of conditions."

In historic events, the so-called great men are labels giving names to events, and like labels they have but the smallest connection with the event itself. Every act of their, which appears to them an act of their own will, is in an historical sense involuntary and is related to the whole course of history and predestined from eternity.

No comments:

Post a Comment