Realism: Introduction. Objectivity. (George Eliot, George Bernard Shaw, Gustave Flaubert, Anton Chekhov)

Realism: Introduction. Objectivity. (George Eliot, George Bernard Shaw, Gustave Flaubert, Anton Chekhov)_____

The shift from Symbolism to Realism is not such an about-face as it might seem, especially when you have a figure like Flaubert who participates in both camps. The chief distinction seems to be in the approach to an audience:Opposing symbolist predilections for an esoteric subject-matter, for perfection of form, and for an elite audience, the realist offers his work as a means of communication among men, dealing with large subjects in a comprehensible way, form subordinated to content.But even here, we'll see, there are different kinds of audiences. The mob still remains somewhat out of the artist's consideration, and realists seem as compelled as symbolists to explain what they're about.

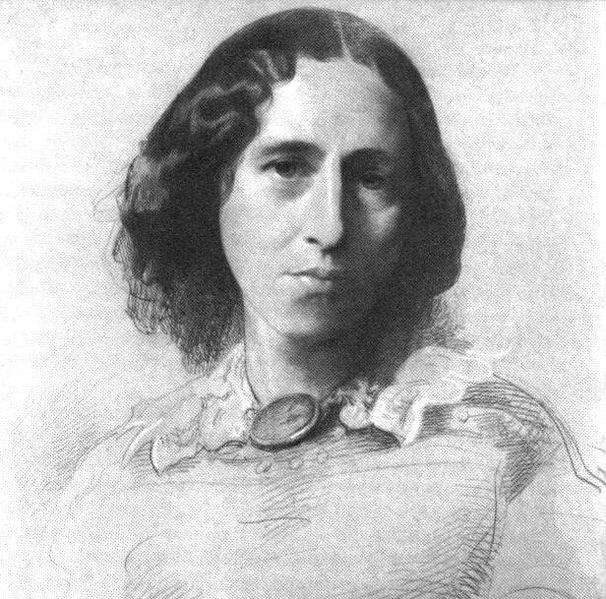

George Eliot: A Realism of Love

|

| Samuel Laurence, Portrait of George Eliot, c. 1860 |

These fellow-mortals, every one, must be accepted as they are: you can neither straighten their noses, nor brighten their wit, nor rectify their dispositions; and it is these people -- amongst whom your life is passed -- that it is needful you should tolerate, pity, and love: it is these more or less ugly, stupid, inconsistent people, whose movements of goodness you should be able to admire -- for whom you should cherish all possible hopes, all possible patience.But what does this have to do with art? they might ask. And Eliot's response would be that art shouldn't lie to you. Moreover, sentimentalizing and simplifying human character is a cop-out: "Falsehood is so easy, truth so difficult." It's easier, she points out, to draw a fantastic creature like a griffin than to make a convincing picture of a real lion.

|

| Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid, c. 1660 |

|

| Adriaen van Ostade, Peasants in an Interior, 1661 |

George Bernard Shaw: False Ideals Exposed

In 1890, Shaw, at the peak of his enthusiasm for Ibsen, writes savagely about the fake idealism that masks hypocrisy. And his remarks have remained pertinent to this day, when "family-values" politicians are constantly being revealed as adulterers, and those who purport to be "saving marriage" turn out to be closeted homosexuals. And fiction has too often played along with them: "In our novels and romances especially we see the most beautiful of all the masks: those devised to disguise the brutalities of the sexual instinct in the earlier stages of its development, and to soften the rigorous aspect of the iron laws by which Society regulates its gratification." In the idealizing of marriage, "men try to graft pleasure on necessity by desperately pretending that the institution forced upon them is a congenial one."

He imagines "a community of a thousand persons," 700 of whom are comfortable with the institution of marriage, and 299 of whom "find it a failure, but must put up with it since they are in a minority." Because they don't want to admit their failure, this minority becomes the loudest in proclaiming that "the family is a beautiful and holy natural institution. For the fox not only declares that the grapes he cannot get are sour: he also insists that the sloes he can get are sweet.... Our 299 domestic failures are therefore become idealists as to marriage; and in proclaiming the ideal in fiction, poetry, pulpit and platform oratory, and serious private conversations, they will far outdo the 700 who comfortably accept marriage as a matter of course, never dreaming of calling it an 'institution,' much less a holy and beautiful one." So in this community there are 299 idealists and 700 Philistines.

But there's one person left over. He sees that marriage is not in itself either holy or beautiful, and that it often fails, so he thinks it "insufferable that two human beings, having entered into relations which only warm affection can render tolerable, should be forced to maintain them after such affections have ceased to exist, or in spite of the fact that they have never arisen. The alleged natural attractions and repulsions upon which the family ideal is based do not exists; and it is historically false that the family was founded for the purpose of satisfying them." But he'll get no support from the 700 Philistines, who are so complacently settled in their situations that they'll "simply think him mad." And the 299 idealists are so terrified at being revealed as failures and hypocrites, that they'll denounce him. "They will crucify him, burn him, violate their own ideals of family affection by taking his children away from him, ostracize him, brand him as immoral, profligate, filthy, and appeal against him to the despised Philistines, specially idealized for the occasion as Society."

Shaw calls on Shelley as an example: "The idealists ... called him a fiend until they invented a new illusion to enable them to enjoy the beauty of his lyrics, this illusion being nothing less than the pretence that since he was at bottom an idealist himself, his ideals must be identical with those of Tennyson and Longfellow, neither of whom ever wrote a line in which some highly respectable ideal was not implicit." So Shaw tackles the problem of the word "idealist," because it's necessary "to distinguish pioneers like Shelley and Ibsen as realists from the idealists of my imaginary community of one thousand."

In Shaw's definition of "realist," he means someone who sees that fake ideals have been concocted as "something to blind us, something to numb us, something to murder self in us, something whereby, instead of resisting death, we can disarm it by committing suicide. The idealist, who has taken refuge with the ideals because he hates himself and is ashamed of himself, thinks that all this is so much the better."

The realist declares that when a man abnegates the will to live and be free in a world of the living and free, seeking only to conform to ideals for the sake of being, not himself, but 'a good man,' then he is morally dead and rotten, and must be left unheeded to abide his resurrection, if that by good luck arrive before his bodily death.

Gustave Flaubert: Heroic Honesty

In 1856, as Madame Bovary was being serialized in La Revue de Paris, Flaubert responded to the critique of its co-editor, Laurence Pichat, that he was as disgusted by some of the details in it too: "I hold the everyday life in detestation.... But aesthetically I wanted this time, and only this time, to exhaust it thoroughly. So I took the thing in an heroic fashion, I mean a minute one, accepting everything, saying everything, depicting everything -- an ambitious statement!" And it took a lot out of him, he wrote to his friend, poet and playwright Louis Bouilhet. His meticulousness and perfectionism was "an insane way of working," and his mother asserted, "The mania for phrases has dried up your heart."

Anton Chekhov: Dunghills as Artistic Material

|

| Anton Chekhov in 1889 |

He chafes against censorship because "The fate of literature would be woeful ... if you left it to the will of individuals.... there is no police which we can consider competent in literary matters.... you cannot find a better police for literature than criticism and the author's own conscience."

And like George Eliot, he defends the choice of lower class figures as artistic material:

To be condescending toward humble people because of their humbleness does not do honor to the human heart. In literature, the lower ranks are as necessary as in the army, -- so says the mind, and the heart ought to confirm this most thoroughly.

No comments:

Post a Comment