_____

Gustave Flaubert: An Aesthetic Mysticism

In letters from various years to Guy de Maupassant, writer and photographer Maxime du Camp, Louise Colet and George Sand, Flaubert returned to the subject of the artist's character and role. To Maupassant he proclaimed that the artist must "sacrifice everything to Art. Life for him must be no more than a means to an end, and the last person he must consider is himself." To du Camp he insisted that he had no interest in being famous, which "can only be entirely satisfying to those with a poor conceit of themselves.... I am aiming at something better, at pleasing myself." Of course, pleasing himself was sometimes difficult: "I would sooner die like a dog than hurry my sentence by so much as a second before it is ripe," even though if he were "much more facile" he "could draw larger profits for much less work. But I can see no remedy."

On the question of the artist's lifestyle, he told Colet, "one should live like a bourgeois and think like a demi-god. Physical and intellectual gratifications have nothing in common. If they happen to coincide, hold fast to them." But the art must take priority: "If you seek happiness and beauty simultaneously, you will attain neither one nor the other, for the price of beauty is self-denial."

Let us therefore seek only tranquillity; let us ask of life only an armchair, not a throne; only water to quench our thirst, not drunkenness. Passion is not compatible with the long patience that is a requisite of our calling. Art is vast enough to take complete possession of a man.And so art takes on the nature of a religion, or rather "a kind of aesthetic mysticism." He takes aim at "the world's socialists, with their eternal materialistic prophesies." He makes prophesies of his own: "At present man's soul is asleep, drugged by the words she has heard; but she will have a frenzied awakening, and give herself over to the joys of liberty; for she will have no restraints left to hold her back, no government, no religion, no principles of any sort. Republicans of all complexions are to me the cruellest pedagogues in the world, with their dreams of organisation, legislation, and a monastically rigid society." As for the future of art, "Poetry ... will not die, but where poetry will come into things in future I can hardly see.... Perhaps beauty will become useless quality to humanity, and Art will be something halfway between algebra and music."

He feels acutely his alienation from the mass of humanity, which "hates us; we do not minister to it and we hate it because it wounds us. Therefore, we must love one another in Art, as the mystics love one another in God, and everything must grow pale before that love." As his alienation from his fellow men widens, he says, "my sensitivity towards all that I find sympathetic continually increases, as a result of this very withdrawal." To George Sand he insisted, "Art ought to be simple. Art, really, is whatever one can make it. We are not free to choose. Each man, willy-nilly, follows his natural course."

E.M. Forster: Art as Evidence of Order

|

| E.M. Forster, date unknown |

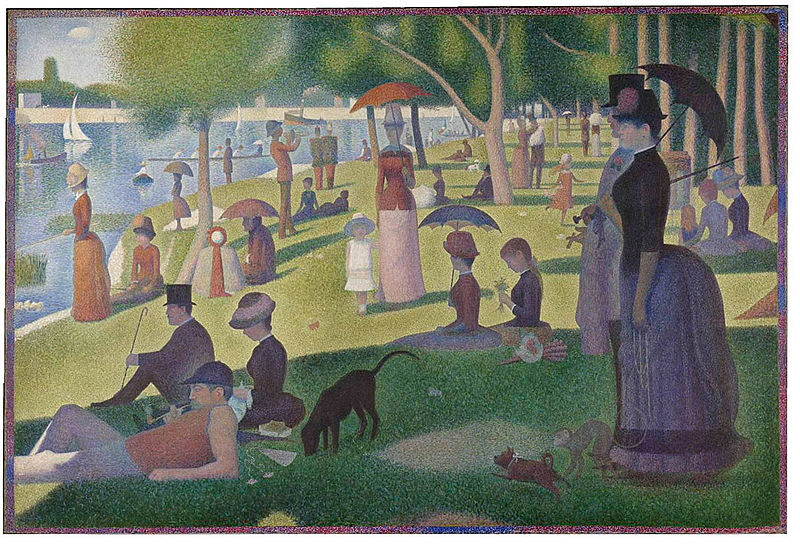

For another example of this premise, he considers Seurat's "La Grande Jatte."

|

| Georges Seurat, Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte, 1884-86 |

Order, I suggest, is something evolved from within, not something imposed from without; it is an internal stability, a vital harmony, and in the social and political category, it has never existed except for the convenience of historians.We can't achieve a permanent social and political order, he posits, because "we continue to make scientific discoveries and to apply them, and thus to destroy the arrangements which were based on more elementary discoveries." If science were pursued for its own sake, and if its discoveries were never turned into applications, "if, in other words, men were more interested in knowledge than in power -- mankind would be in a far safer position, the stability statesmen talk about would be a possibility, there could be a new order based on vital harmony, and the earthly millennium might approach." But it's not going to happen.

So our experience of order seems to Forster to be limited two only possible sources. One of them is "the divine order, the mystic harmony, which according to all religions is available for those who can contemplate it." But Forster admits that he's not one of that elect. The remaining one is "the aesthetic category ... the order which an artist can create in his own work." It stands outside the social order: "Ancient Athens made a mess -- but the Antigone stands up. Renaissance Rome made a mess -- but the ceiling of the Sistine got painted. James I made a mess -- but there was Macbeth. Louis XIV -- but there was Phèdre." Art, in short, "is the one orderly product which our muddling race has produced."

Because of this, the artist has always been an outsider, "and ... the nineteenth century conception of him as a Bohemian was not inaccurate."

If our present society should disintegrate -- and who dare prophesy that it won't? -- this old-fashioned and démodé figure will become clearer: the Bohemian, the outsider, the parasite, the rat -- one of those figures which have at present no function either in a warring or a peaceful world.... Works of art, in my opinion, are the only objects in the material universe to possess internal order, and that is why, though I don't believe that only art matters, I do believe in Art for Art's Sake.

Arthur Rimbaud: The Poet as Revolutionary Seer

|

| Arthur Rimbaud in 1871 |

In both letters, Rimbaud makes the famous statement "I is someone else," which is no more or less grammatical in the French "Je est un autre." The poet is not born but made, just as the musical instrument is formed out of raw materials: To Izambard he says, "So much the worse for the wood if it find itself a violin," and to Demeny, "If brass wakes up a trumpet, it is not its fault." Making the poet responsible for his poem is an error: "The Romantics ... proved so clearly that the song is very seldom the work, that is to say, the idea sung and intended by the singer."

The poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and rational disordering of all the senses. Every form of love, of suffering, of madness; he searches himself, he consumes all the poisons in him, and keeps only the quintessences.Like Shelley, he sees the poet as Prometheus: "the poet really is the thief of fire." And in his role as seer and rebel, he brings in "the new -- in ideas and in forms."

Stéphane Mallarmé: Art as Aristocratic Mystery

As the essay "Art for All" (1862) demonstrates, the young Mallarmé (he was barely 20) is not at all concerned about art becoming elitist. "Art has its own mysteries," he proclaims, and exemplifies this by music, whose system of notation -- "those macabre processions of rigid, chaste, and undeciphered signs" -- is a barrier to the uninitiated. But poetry "faces hypocritical curiosity without mystery, blasphemy without terror, and suffers the smiles and grimaces of the ignorant and hostile," being made up of words that even the barely literate can approach without difficulty. "Poetry, like all things of perfect beauty, is perforce admired. But the admiration is distant, vague -- a stupid admiration since it is the mob's." It gets taught in the schools, "explained to all alike, democratically."

The visual arts also share this accessibility by the mob, to the "citizen [who] strides through our museums with a careless freedom and an absent-minded frigidity which he would not dare exhibit even in a church." But "music, painting, and sculpture are .. left to 'those who are in the business,' whereas people learn poetry because they want to appear educated." He backs off from sneering at the "mob" a bit, quoting with approval Baudelaire's statement, "To insult the mob is to degrade oneself." The poet is simply of a different order from the masses: "Let us remember that the poet (whether he rhymes, sings, paints, or sculptures) is not on a level beneath which other men crawl; the mob is a level and the poet flies above it. Seriously, has the Bible ever told us that angels mock man because he has no wings?"

Art, he argues, should remain "a mystery accessible only to the very few." Popularity should not be a test for the artist. It should even be regarded as a stigma.

You may say: "What of Corneille, Molière, and Racine? They are popular and glorious." No, they are not popular. Their names are popular, perhaps; but their poetry is not. The mob has read them once, that is true; and without understanding them. But who rereads them? Only artists.And so, in the face of universal education, he argues against letting the arts become too popular: "If there is a popularization, let us make sure that it is a popularization of the good, not of the beautiful.... Let the masses read works on moral conduct; but please don't let them ruin our poetry."

W.H. Auden: Poetry as a Game of Knowledge

|

| W.H. Auden, date unknown |

Sometimes he unpacks his aphorisms for us: "The poet is the father who begets the poem which the language bears." He explains that poet and language are husband and wife, and it is the poet, "not the language, who is responsible for the success of their marriage, which differs from natural marriage in that in this relationship there is no loveless lovemaking, no accidental pregnancies."

Among the theories of poetry that he dislikes is "Poetry as a magical means for inducing desirable emotions and repelling undesirable emotions in oneself and others." The Greeks, he says, held this view, because they "confused art with religion." But despite this, they produced great art because "they were frivolous people who took nothing seriously. Their religion was just a camp." More worrisome are those in our own day who take things too seriously and try to make art serve their ends, creating "dishonest and insufferably earnest and boring Agit-Prop for Christianity, Communism, Free Enterprise or what have you."

Auden prefers the theory of "Poetry as a game of knowledge, a bringing to consciousness, by naming them, of emotions and their hidden relationships." In the spirit of "How can I know what I think till I see what I say?" the poet tries out words in various combinations and permutations until he or she finds what works. And because poetry stumbles when it becomes involved in too serious matters of daily life, it needs to distance itself from events too large for words:

There are events which arouse such simple and obvious emotions that an AP cable or a photograph in Life magazine are enough and poetic comment is impossible. If one reads through the mass of versified trash inspired, for instance, by the Lidice Massacre, one cannot avoid the conclusion that what was really bothering the versifiers was a feeling of guilt at not feeling horrorstruck enough. Could a good poem have been written on such a subject? Possibly. One that revealed this lack of feeling, that told how when he read the news, the poet, like you and I, dear reader, went on thinking about his fame or his lunch, and how glad he was that he was not one of the victims.In fact, Auden wrote such a poem, and is perhaps too modest to mention it here, so I will:

Musée des Beaux Arts

About suffering they were never wrong,The Old Masters: how well they understoodIts human position; how it takes placeWhile someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waitingFor the miraculous birth, there always must beChildren who did not specially want it to happen, skatingOn a pond at the edge of the wood:They never forgotThat even the dreadful martyrdom must run its courseAnyhow in a corner, some untidy spotWhere the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horseScratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns awayQuite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman mayHave heard the splash, the forsaken cry,But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shoneAs it had to on the white legs disappearing into the greenWater; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seenSomething amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

(A commentary on this poem, and some other poets' responses to it, can be found here.) The detachment of the poet from the ostensible subject of his poem is essential: "The girl whose boy-friend starts writing her love poems should be on her guard. Perhaps he really does love her, but one thing is certain: while he was writing his poems he was not thinking of her but of his own feelings about her, and that is suspicious."

He takes Shelley to task for "the silliest remark ever made about poets, 'the unacknowledged legislators of the world.' ... Sounds more like the secret police to me." But his admitted dislike of Shelley's poetry may have betrayed him into misreading the statement. And like Mallarmé, he mistrusts what he doesn't call "the mob," but clearly means pretty much what Mallarmé meant by the phrase, lamenting that, on the evidence of a favorite-poem feature in the Sunday Times, "millions in their bereavements, heartbreaks, agonies, depressions, have been comforted and perhaps saved from despair by appalling trash while poetry stood helplessly and incompetently by."

Most of all, he rejects extravagant claims for poetry:

A society which really was like a poem and embodied all the esthetic values of beauty, order, economy, subordination of detail to the whole effect, would be a nightmare of horror, based on selective breeding, extermination of the physically or mentally unfit, absolute obedience to its Director, and a large slave class kept out of sight in cellars.

E.M. Forster couldn't have said it better (and didn't).

And like Rimbaud, he recognizes the need for the poet to experience the disorderly life, with a wonderfully perceptive comment about the two most famous tellings of the Faust legend: "Marlowe was not as intelligent as Goethe but he had more common sense. At least he knew that Faust went to hell. Faust is damned, not because he has sinned, but because he made a pact with the Devil, that is, like a poet he planned a life of sin beforehand.

W.H. Auden: Poetry as Rite

"Making, Knowing, and Judging" (1956) gives us a more sober, less aphoristic Auden. It acknowledges that poetry demands a special orderliness to serve its function:

A poem is a rite; hence its formal and ritualistic character. Its use of language is deliberately and ostentatiously different from talk. Even when it employs the diction and rhythms of conversation, it employs them as a deliberate informality, presupposing the norm with which they are intended to contrast.

Again, the focus is on language, but on using language to pay homage to the poet's experience of the world. "In poetry the rite is verbal; it pays homage by naming."

Artistic style, he observes, reflects the changes in society's imagining of "the frontier between the sacred and the profane.... the Baroque architect did not aim, as a modern architect aims when designing a government office in which the king could govern as easily and efficiently as possible; he was trying to make a home fit for God's earthly representative to inhabit.... Even today few people find a functionally furnished living-room beautiful because, to most of us, a sitting-room is not merely a place to sit in; it is also a shrine for father's chair."

So "every poem is rooted in imaginative awe.... but there is only one thing that all poetry must do; it must praise all it can for being as for happening."

Wallace Stevens: Art as Establisher of Value

|

| Wallace Stevens, date unknown |

No poet that I know of has more explicitly taken the imagination itself as the subject of his or her poetry. Coleridge, Shelley and Keats theorized about the imagination, but in their poems they addressed its function through metaphor: the construction of a stately pleasure-dome, the blowing of the west wind, the contemplation of a Grecian urn. Stevens has his metaphors too: a blue guitar, blackbirds, a jar on a hill in Tennessee, and so on. But he is consistently open about the fact that his great subject is the function of the imagination. So his prose disquisitions on the topic might be supererogatory, but we welcome them anyway because the prose is so, well, Stevensesque.

The poet's role, Stevens says, is "to supply the satisfactions of belief" in an age without belief. We have suffered a sense of loss with the fading of religious belief, even though "To see the gods dispelled in mid-air and dissolve like clouds is one of the great human experiences." The desire for the colossal presences of the gods remains, in part because "Their fundamental glory is the fundamental glory of men and women, who being in need of it create it, elevate it, without too much searching of its identity." Man created God in his own image: "The people, not the priests, made the gods."

Let us stop now and restate the ideas which we are considering in relation to one another. The first is that the style of a poem and the poem itself are one; the second is that the style of the gods and the gods themselves are one; the third is that in an age of disbelief, when the gods have come to an end, when we think of them as the aesthetic projections of a time that has passed, men turn to a fundamental glory of their own and from that create a style of bearing themselves in reality. They create a new style of a new bearing in a new reality.

Poetry's role in this comes from its nature as "an interdependence of the imagination and reality as equals." But the poet must not consider that he or she holds any obligation to society or to morality: "the all-commanding subject-matter of poetry is life, the never-ceasing source." And that emancipates the poet from any social or political role: "No politician can command the imagination, directing it to do this or that. Stalin might grind his teeth the whole of a Russian winter and yet all the poets in the Soviets might remain silent the following spring. He might excite their imaginations by something he said or did. He would not command them."

The poet's role with regard to his or her audience "is to make his imagination theirs and ... he fulfills himself only as he sees his imagination become the light in the mind of others." But Stevens concurs with Mallarmé in observing that "There is not a poet whom we prize living today that does not address himself to an élite." And he seconds I.A. Richards in proclaiming the poet's "role is to help people to live their lives. He has had immensely to do with giving life whatever savor it possesses. He has had to do with whatever the imagination and the senses have made of the world." And like Klee, he argues that the artist "has to discover the possible work of art in the real world, then to extract it, when he does not himself compose it entirely; ... art sets out to express the human soul; and ... everything like a firm grasp of reality is eliminated from the aesthetic field."

And like everyone who has read Wilde, he realizes that nature imitates art: "what makes the poet the potent figure that he is, or was, or ought to be, is that he creates the world to which we turn incessantly and without knowing it and that he gives to life the supreme fictions without which we are unable to conceive of it." But they are and remain fictions: "A poet's words are of things that do not exist without the words.... It is not only that the imagination adheres to reality, but, also, that reality adheres to the imagination and that the interdependence is essential." So in this regard, poetry is "at least the equal of philosophy."

Essentially, "the imagination is the power that enables us to perceive the normal in the abnormal, the opposite of chaos in chaos."

The exploits of Rimbaud in poetry, if Rimbaud can any longer be called modern, and of Kafka in prose are deliberate exploits of the abnormal. It is natural for us to identify the imagination with those that extend its abnormality. It is like identifying liberty with those that abuse it.... The truth seems to be that we live in concepts of the imagination before the reason has established them. If this is true, then reason is simply the methodizer of the imagination.

To some this sounds frivolous, an avoidance of the harshness of reality, of "the solitude and misery and terror of the world.... But when we speak of perceiving the normal we have in mind the instinctive integrations which are the reason for living. Of what value is anything to the solitary and those that live in misery and terror, except the imagination?"

No comments:

Post a Comment