Realism: Naturalistic Determinism (Theodore Dreiser, Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, Émile Zola)

Realism: Naturalistic Determinism (Theodore Dreiser, Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, Émile Zola)_____

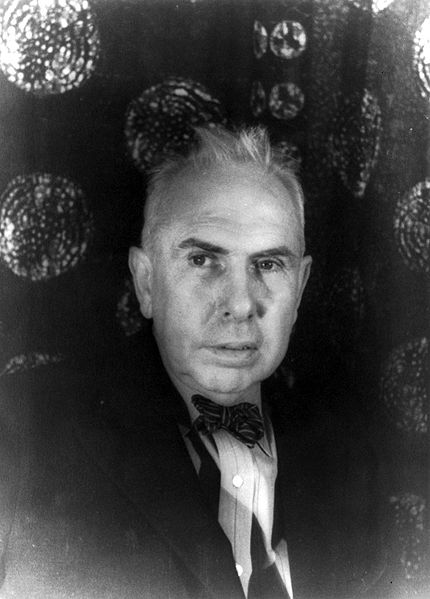

Theodore Dreiser: Man as Natural Mechanism

In his autobiographical Newspaper Days or a Book About Myself (1922), Dreiser recalls the process by which he turned away from Roman Catholicism toward an acceptance of a scientific view of humankind:

Theodore Dreiser in 1933 Of one's ideals, struggles, deprivations, sorrows and joys, it could only be said that they were chemic compounds, something which for some inexplicable but unimportant reason responded to and resulted from the hope of pleasure and the fear of pain. Man was a mechanism, undevised and uncreated, and a badly and carelessly driven one at that.

His newspaper work only tended to confirm this pessimistic view of humanity, sending him into the most sordid parts of Chicago and St. Louis. "With a gloomy eye I began to watch how the chemical -- and their children, the mechanical -- forces operated through man and outside him, and this under my very eyes." (A great prose stylist, Dreiser wasn't.) Nor did his encounter with the editors, who represented the rich and the powerful, tend to alleviate his gloom. "All I could think of was that since nature would not or could not do anything for man, he must, if he could, do something for himself; and of this I saw no prospect, he being a product of these self-same accidental, indifferent and bitterly cruel forces."

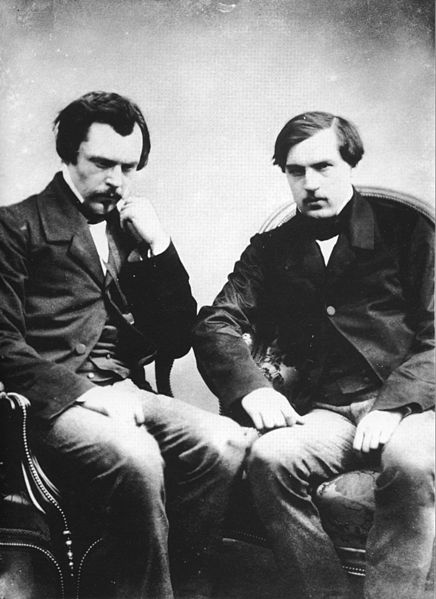

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt: Clinical Realism

|

| Edmond (left) and Jules de Goncourt, date unknown |

The Goncourt brothers are more famous for their journal than for their novels, but the preface to Germinie Lacerteux (1864) provides an explanation of their approach to fiction, the product of their association with virtually every French writer of prominence in the mid-nineteenth century. They defend their novel -- most realists spent a lot of time defending their work -- not on the grounds of its scientific significance, as Zola would, or on the grounds of the privileged autonomy of art, as Flaubert might, but because of its social utility.

The novel, they say, "is beginning to be the serious, impassioned, living form of literary study and social investigation" and "the true History of contemporary morals," a role that Taine might have proposed for it. Hence, it deserves "its liberty and freedom of speech." Moreover, it serves a charitable purpose, by illuminating "the visible, palpitating human suffering that teaches charity." It serves in "the practice of that religion which the last century called by the vast and far-reaching name, Humanity" and therefore "needs no other warrant than the consciousness that that is its right."

Émile Zola: The Novel as Social Science

|

| Edouard Manet, Portrait of Émile Zola, 1868 |

Nothing takes us further from "art for art's sake," from the assertions of the purity and autonomy of art, from the Wildean claim that art is useless, than Zola's 1880 essay, "The Experimental Novel." Zola proclaims a particular function for the novel: an experimental one.

Basing the essay on his reading of a treatise on experimental medicine by Claude Bernard, Zola develops a theory of the utility of fiction as a kind of laboratory for human behavior.

The end of all experimental method, the boundary of all scientific research, is ... identical for living and for inanimate bodies; it consists in finding the relations which unite a phenomenon of any kind to its nearest cause, or, in other words, in determining the conditions necessary for the manifestation of this phenomenon. Experimental science has no necessity to worry itself about the "why" of things; it simply explains the "how."

Would it were that simple, but let's give Zola a little room to make his case.

So the question is: "Is experiment possible in literature, in which up to the present time observations alone has been employed?" Zola defines "experiment" as "provoked observation," and presents the novelist as "equally an observer and an experimentalist."

The observer in him gives the facts as he has observed them, suggests the point of departure, displays the solid earth on which his characters are to tread and the phenomena to develop. Then the experimentalist appears and introduces an experiment, that is to say, sets his characters going in a certain story so as to show that the succession of facts will be such as the requirements of the phenomena under examination call for.

Zola follows with an example from Balzac's Cousine Bette, and asserts, "If we bear in mind this definition, that 'observation indicates and experiment teaches,' we can even now claim for our books this great lesson of experiment." So Zola in effect claims as a function of the novel something that the symbolists unanimously rejected: didacticism.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Paul Alexis Reading a Manuscript to Zola, 1869-70 |

For "naturalistic novelists," he says, "all their work is the offspring of the doubt which seizes them in the presence of truths little known and phenomena unexplained, until an experimental idea rudely awakens their genius some day, and urges them to make an experiment, to analyze facts, and to master them." And thus, he asserts, "purely imaginary novels" have begun to replace "novels of observation and experiment."

Like Tolstoy, Zola is a determinist. "All that can be said is that there is an absolute determinism for all human phenomena." But unlike Tolstoy, Zola is not content to let this rest as an unknowable mystery: "now that we possess the tool, the experimental method, our goal is very plain -- to know the determinism of phenomena and to make ourselves master of these phenomena." He goes so far as to claim that eventually we will understand "the mechanism of the thoughts and passions; we shall know how the individual machinery of each man works; how he thinks, how he loves, how he goes from reason to passion and folly."

But he is also aware that the individual is worked on by larger forces: "Man is not alone; he lives in society, in a social condition; and consequently, for us novelists, this social condition unceasingly modifies the phenomena." This throws him into a bit of a muddle -- "We are not yet able to prove that the social condition is also physical and chemical" -- but he remains confident that scientific progress will be able to sort it out.

And this is what constitutes the experimental novel: to possess a knowledge of the mechanism of the phenomena inherent in man, to show the machinery of his intellectual and sensory manifestations, under the influences of heredity and environment, such as physiology shall give them to us, and then finally to exhibit man living in social conditions produced by himself, which he modifies daily, and in the heart of which he himself experiences a continual transformation.

The main thing, Zola says, citing Bernard as his authority, is to concentrate on the "how" and forget about the "why" of things. Stick with the observable and forget about the metaphysical. This will be the goal of "the literature of our scientific age, as the classical and romantic literature corresponded to a scholastic and theological age."

The ultimate purpose of science (and by extension literature in a scientific age) is mastery of nature: "We shall enter upon a century in which man, grown more powerful, will make use of nature and will utilize its laws to produce upon the earth the greatest possible amount of justice and freedom." (That century obviously was not the twentieth, and certainly doesn't look like it's going to be the twenty-first.) To attain this is "the practical utility and high morality of our naturalistic works."

To be the master of good and evil, to regulate life, to regulate society, to solve in time all the problems of socialism, above all, to give justice a solid foundation by solving through experiment the questions of criminality -- is not this being the most useful and the most moral workers in the human workshop?

And so he sets the naturalist writer against "idealistic" writers, those "who cast aside observation and experiment, and base their works on the supernatural and the irrational, who admit, in a word, the power of mysterious forces outside of the determinism of the phenomena." The naturalist must be willing to get down in the muck of existence, as Bernard says the physiological researcher must: "You will never reach really fruitful and luminous generalizations on the phenomena of life until you have experimented yourself and stirred up in the hospital, the amphitheater, and the laboratory the fetid or palpitating sources of life."

He joins Bernard in distinguishing between determinism and fatalism: "the moment that we can act, and that we do act, on the determining cause of phenomena -- by modifying their surroundings, for example -- we cease to be fatalists." And the experimental novelist has no need to draw conclusions from the events in his novels, to point toward some sort of moral lesson: "our works carry their conclusion with them. An experimentalist has no need to conclude, because, in truth, experiment concludes for him." Because the experimental writer is working toward the great goal of conquering nature and increasing human power over it, he is superior to "the idealistic writers, who rely upon the irrational and the supernatural, and whose every flight upward is followed by a deeper fall into metaphysical chaos. We are the ones who possess strength and morality."

It follows, then, that Zola rejects poetry. "If you are content to ... enjoy your own feelings without finding any basis for it in reason or any verification in experiment, you are a poet; you venture upon hypotheses which you cannot prove; you are struggling vainly in a painful indeterminism, and in a way that is often injurious."

Our age of lyricism, our romantic disease, was alone capable of measuring a man's genius by the quantity of nonsense and folly which he put into circulation. I conclude by saying that in our scientific century experiment must prove genius.... There is neither nobility, nor dignity, nor beauty, nor morality in not knowing, in lying, in pretending that you are greater according as you advance in error and confusion. The only great and moral works are those of truth.

Naturalism is, he proclaims, "the intellectual movement of the century." But Zola doesn't entirely reject philosophy, quoting Bernard: "From a scientific point of view, philosophy represents the eternal desire of the human reason after knowledge of the unknown." And therefore it inspires and validates the scientific quest. (Zola characterizes Bernard's view of the role of the philosophers as that of "musicians who play a sort of Marseillaise made up of hypotheses, and swell the heart of the savants as they rush to attack the unknown.") But Zola thinks that it's time for the philosophers to stand aside and recognize "that their hypotheses are pure poetry."

The poets also put too much emphasis on "form" and "style." But Zola asserts that the best style is the one that communicates truth: "We are actually rotten with lyricism; we are very much mistaken when we think that the characteristic of a good style is a sublime confusion with just a dash of madness added; in reality, the excellence of a style depends upon its logic and clearness." And he insists that "the thought of a great savant who knows how to write is much more interesting than that of a poet."

He parts company with Barnard on his assertion that "In arts and letters personality dominates everything." He must be thinking of "lyrical poetry," Zola says, "for he never could have written that phrase had he understood the experimental novel as shown in the works of Balzac and Stendhal.... Our field is the same as the physiologist, only that it is greater." And he rejects Barnard's definition of an artist as "a man who realizes in a work of art an idea or a sentiment which is personal to him." Zola insists "that the personal feeling of the artist is always subject to the higher law of truth and nature."

As for the prophetic role of the artist, he wants it "understood that these prophets rely neither upon the irrational nor the supernatural.... In our scientific age it is a very delicate thing to be a prophet, as we no longer believe in the truths of revelation, and in order to be able to foresee the unknown we must begin by studying the known."

Finally, Zola makes a nod to the hallowed concept of "beauty," agreeing that the Iliad ("Achilles' Anger") and the Aeneid ("Dido's Love") "will last forever on account of their beauty; but to-day we feel the necessity of analyzing anger and love, of discovering exactly how such passions work in the human being."

No comments:

Post a Comment