Chapter 7: Philadelphia, and Its Solitary Prison; Chapter 8: Washington. The Legislature. And the President's House.

Chapter 7: Philadelphia, and Its Solitary Prison; Chapter 8: Washington. The Legislature. And the President's House._____

I'm sure this joke has been made before, but sometimes it seems like American Notes should really have been titled Great Expectorations. The attack on the American habit of spitting begins on the train ride from New York to Philadelphia, in which Dickens observes that the "gentlemen's car" in front of the one in which he was riding seemed to containa number of industrious persons inside, ripping open feather-beds, and giving the feathers to the wind. At length it occurred to me that they were only spitting, which was indeed the case; though how any number of passengers which it was possible for that car to contain, could have maintained such a playful and incessant shower of expectoration, I am still at a loss to understand.In any case, it is only a prelude to what Dickens calls the "salivatory phenomena" that he subsequently documents.

|

| The Second Bank of the United States |

From his hotel room in Philadelphia, Dickens looks out on "a handsome building of white marble, which had a mournful, ghost-like aspect, dreary to behold." He learns that the building is "the Tomb of many fortunes; the Great Catacomb of investment; the memorable United States Bank" whose failure in 1841 was a financial disaster. The phrase "too big to fail" had not yet been coined.

Philadelphia itself "is a handsome city, but distractingly regular. After walking about it for an hour or two, I felt that I would have given the world for a crooked street." As usual, he inspects the various public institutions, including "a most excellent Hospital -- a quaker establishment, but not sectarian in the great benefits it confers," and which contains "a picture by West, which is exhibited for the benefit of the funds of the institution. The subject is, our Saviour healing the sick, and it is, perhaps, as favourable a specimen of the master as can be seen anywhere. Whether this be high or low praise, depends upon the reader's taste." (Dickens, one suspects, didn't care much for it.)

|

| Benjamin West, Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple |

In the outskirts, stands a great prison, called the Eastern Pentitentiary; conducted on a plan peculiar to the state of Pennsylvania. The system here, is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong.

| ||

| The State Penitentiary for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1855. |

|

| A contemporary re-creation of a cell at the Eastern Penitentiary |

On the haggard face of every man among these prisoners, the same expression sat. I know not what to liken it to. It had something of that strained attention which we see upon the faces of the blind and deaf, mingled with a kind of horror, as though they had all been secretly terrified.He does find, however, that the women prisoners seem to fare better than the men, "Whether this be because of their better nature, which is elicited in solitude, or because of their being gentler creatures, of greater patience and longer suffering, I do not know; but so it is." He even observes that solitary confinement seems to dull the prisoners' sense of hearing, an impression confirmed in a conversation with one of the prisoners.

From Philadelphia they go by steamboat to Washington, encountering on the journey some fellow Englishmen who turn out to "display an amount of insolent conceit and cool assumption of superiority, quite monstrous to behold." So much so, "that I would cheerfully have submitted to a reasonable fine, if I could have given any other country in the whole world, the honour of claiming them for its children."

But Washington turns out to be "the head-quarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva" and he regrets that he had once been persuaded "that previous tourists have exaggerated its extent. The thing itself is an exaggeration of nastiness, which cannot be overdone." He is also unnerved by a stop at Baltimore where they "were waited on, for the first time, by slaves." And he experiences the downside of celebrity, when, transferring to a train, they are beset by gawkers who "feel to comparing notes on the subject of my personal appearance, with as much indifference as if I were a stuffed figure. I never gained so much uncompromising information with reference to my own nose and eyes, and various impressions wrought by my mouth and chin on different minds, and how my head looks when it is viewed from behind."

|

| The United States Capitol, c. 1840. The original dome was replaced in 1855. |

Take the worst parts of the City Road and Pentonville, or the straggling outskirts of Paris, where the houses are smallest, preserving all their oddities, but especially the small shops and dwellings.... Burn the whole down; build it up again in wood and plaster; widen it a little; throw in parts of St. John's Wood; put green blinds outside all the private houses, with a red curtain and a white one in every window; plough up all the roads; plant a great deal of coarse turf in every place where it ought not to be; erect three handsome buildings in stone and marble, anywhere, but the more entirely out of everybody's way the better; call one the Post Office, one the Patent Office, and one the Treasury; make it scorching hot in the morning, and freezing cold in the afternoon, with an occasional tornado of wind and dust; leave a brick-field without all the bricks, in all central places where a street may naturally be expected, and that's Washington.And he has no hopes for improvement: "Such as it is, it is likely to remain." That's because its only source of income is the government: "It has no trade or commerce of its own." It is also "very unhealthy."

He admires the Capitol rotunda, but is less impressed with Horatio Greenough's statue of George Washington, which "struck me as being rather strained and violent for its subject." But then he ventures into Congress, which doesn't impress him at all: "In the first place -- it may be from some imperfect development of my organ of veneration -- I do not remember having ever fainted away, or having even been moved to tears of joyful pride, at sight of any legislative body." But he is infuriated by the attacks in the United States Congress against members who oppose "the infamy of that traffic, which has for its accursed merchandise men and women, and their unborn children." He admits that among the congressmen and senators there are men of "intelligence and refinement: the true, honest, patriotic heart of America, ... but they scarcely coloured the stream of desperate adventurers which sets that way for profit and for pay." He also acknowledges that "the distinguished gentleman who is now [the United States'] Minister at the British Court sustains its highest character abroad." (The ambassador to Great Britain in 1842 was Edward Everett.) And of course, Congress is full of spitters:

Both houses are handsomely carpeted; but the state to which these carpets are reduced by the universal disregard of the spittoon with which every honourable member is accommodated, and the extraordinary improvements on the pattern which are squirted and dabbled upon it in every direction, do not admit of being described.

|

| Daguerreotype of the south front of the White House in 1846, the first known photograph of the building |

|

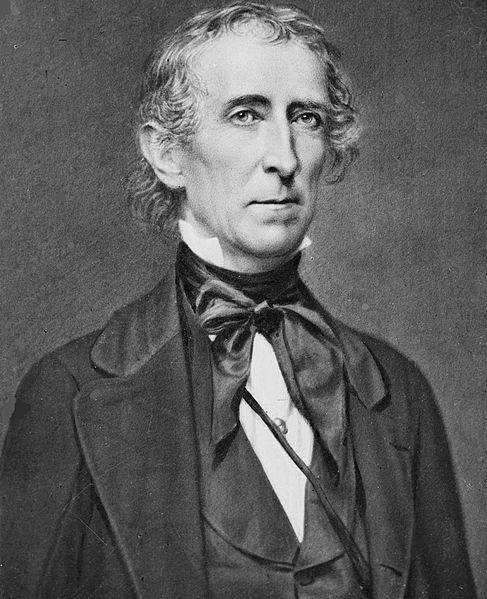

| John Tyler, daguerreotype by Mathew Brady, 1845 |

The "premature heat of the season" makes Dickens change his plans to go south to Charleston, which would also expose him to "the pain of living in the constant contemplation of slavery." So he decides instead to "listen to old whisperings which had often been present to me at home in England, when I little thought of ever being here; and to dream again of cities growing up, like palaces in fairy tales, among the wilds and forests of the west."

No comments:

Post a Comment