Chapter 5: Worcester. The Connecticut River. Hartford. New Haven. To New York.; Chapter 6: New York.

Chapter 5: Worcester. The Connecticut River. Hartford. New Haven. To New York.; Chapter 6: New York._____

And so into the hinterlands, with a first stop at the "pretty New England town" of Worcester, Mass. Dickens notes, parenthetically, that many of the towns and cities of New England "would be villages in Old England." He also observes that "The well-trimmed lawns and green meadows of home are not there; and the grass, compared with our ornamental plots and pastures, is rank, and rough, and wild." And once again, it's the newness of everything that amazes him: "All the buildings looked as if they had been built and painted that morning, and could be taken down on Monday with very little trouble." But the town lacks the picturesqueness he's accustomed to: "It would have been the better for an old church; better still for some old graves." (Wait a century or so, and tourists will flock to New England for precisely that sense of antiquity and stability.)From Worcester, they travel by rail to Springfield, and thence by steamboat to Hartford on the Connecticut River, which is unusually free of ice for this time of year -- it was only "the second February trip, I believe, within the memory of man." The boat strikes him as tiny, but he notes that even in the "Lilliputian" cabin "there was a rocking-chair. It would be impossible to get on anywhere, in America, without a rocking chair." The weather was bad -- not one of those crystal-clear days he has remarked on earlier: "It rained all day as I once thought it never did rain anywhere, but in the Highlands of Scotland" -- but they were wrapped up well and "bade defiance to the weather, and enjoyed the journey."

They stay in Hartford for four days, but Dickens finds little to remark on except that

It is the seat of the local legislature of Connecticut, which sage body enacted, in bygone times, the renowned code of "Blue Laws," in virtue whereof, among other enlightened provisions, any citizen who could be proved to have kissed his wife on Sunday, was punishable, I believe, with the stocks. Too much of the old Puritan spirit exists in these parts to the present hour.Otherwise, he "found the courts of law here, just the same as at Boston; the public institutions almost as good." As usual, he visits an institution for the mentally ill, and is charmed once again by the way the staff humors the delusions of the inmates. A woman approaches him and asks for his autograph, which he grants. Once she leaves, he asks the doctor, "I hope she is not mad?" But she is, the doctor admits: "She hears voices in the air." Which provokes Dickens to wish that "a few false prophets of these later times, who have professed to do the same" could be institutionalized: "I should like to try the experiment on a Mormonist or two to begin with."

They go by railroad to New Haven, where they admire the abundance of elm trees, especially those that "surround Yale College, an establishment of considerable eminence and reputation.... The effect is very like that of an old cathedral yard in England; and when their branches are in full leaf, must be extremely picturesque." The trees give New Haven "a very quaint appearance: seeming ot bring about a kind of compromise between town and country."

|

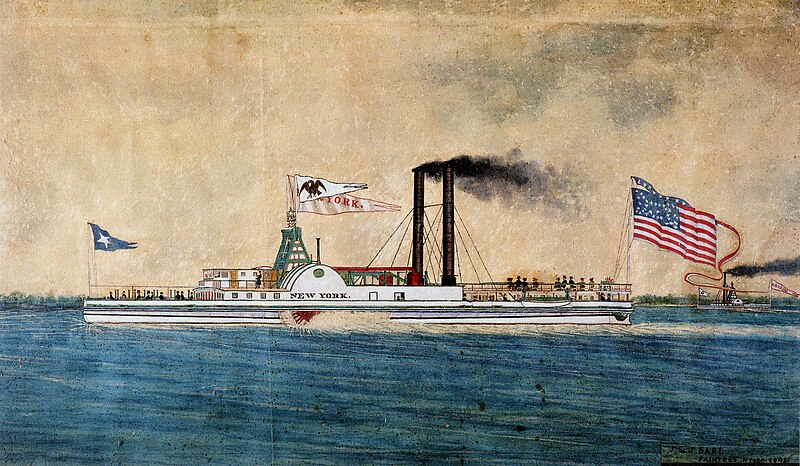

| The New York, a Long Island Sound steamboat built in 1836 |

The beautiful metropolis of America is by no means so clean a city as Boston, but many of its streets have the same characteristics; except that the houses are not quite so fresh-coloured, the sign-boards are not quite so gaudy, the gilded letters not quite so golden, the bricks not quite so red, the stone not quite so white, the blinds and area railings not quite so green, the knobs and plates so bright and twinkling.

|

| Looking south on lower Broadway toward Trinity Church, 1834 |

|

| The Halls of Justice, known as The Tombs, c. 1870 |

Back on the streets, Dickens observes the swine that roam the city, serving as scavengers. "Ugly brutes they are; having, for the most part, scanty brown backs, like the lids of old horsehair trunks: spotted with unwholesome black blotches. They have long, gaunt legs, too, and such peaked snouts, that if one of them could be persuaded to sit for his profile, nobody would recognise it for a pig's likeness." When night falls, Broadway grows quiet, for there are no street musicians and performers, and as he will later tell us, the theaters for which it became famous didn't exist then. The sole "amusements" he can find are the newspapers hawked by "precocious urchins" that deal

in round abuse and blackguard names; pulling off the roofs of private houses, ... pimping and pandering for all degrees of vicious taste, and gorging with coined lies the most voracious maw; imputing to every man in public life the coarsest and vilest motives; scaring away from the stabbed and prostrate body-politic, every Samaritan of clear conscience and good deeds; and setting on, with yell and whistle and the clapping of foul hands, the vilest vermin and worst birds of prey.Dickens now ventures into the slum known as Five Points, "narrow ways, diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth." He is taken into a place that turns out to be a kind of barracks for poor blacks, where "the floor is covered with heaps of negro women, waking from their sleep; their white teeth chattering, and their bright eyes glistening and winking on all sides with surprise and fear.... Where dogs would howl to lie, women, and men, and boys slink off to sleep, forcing the dislodged rats to move away in quest of better lodgings."

Then he is taken to a place where black performers dance for the amusement of customers:

|

| William Henry Lane ("Master Juba") dances in New York's Five Points District as Charles Dickens and a companion watch in the background. Engraving from American Notes by Charles Dickens (1842). |

Nor is he cheered by a visit he makes "to the different public institutions on Long Island, or Rhode Island: I forget which." (He presumably means Long Island, since a trip to Rhode Island would take him a long way back in the direction he came from.) He visits another "Lunatic Asylum," but in this one he doesn't find the atmosphere of tolerance that he found in the ones in New England: "The terrible crowd with which these halls and galleries were filled, so shocked me, that I abridged my stay within the shortest limits and declined to see that portion of the building in which the refractory and violent were under closer restraint." He ascribes the difference of this institution to the fact that its management consists of the beneficiaries of political patronage:

the miserable strife of Party feeling is carried even into this sad refuge of afflicted and degraded humanity.... Will it be believed that the governor of such a house as this, is appointed, and deposed, and changed perpetually, as Parties fluctuate and vary....? A hundred times in every week, some new most paltry exhibition of that narrow-minded and injurious Party Spirit, which is the Simoom of America, sickening and blighting everything of wholesome life within its reach, was forced upon my notice.The Alms House, an institution for the poor, is no better, though he observes that "The prison for the State at Sing Sing, is, on the other hand, a model jail." And there are in New York, he notes, "excellent hospitals and schools, literary institutions and libraries; an admirable fire department (as indeed it should be, having constant practice), and charities of every sort and kind."

But there are only "three principal theatres," and two of them "are, I grieve to write it, generally deserted. The third, the Olympic, is a tiny show-box for vaudevilles and burlesques." And there is "a small summer theatre, called Niblo's ... but I believe it is not exempt from the general depression under which Theatrical Property, or what is humorously called by that name, unfortunately labours." Niblo's and other theaters would later thrive.

While in New York, he books his return ticket for June, "the month in which I had determined, if prevented by no accident in the course of my ramblings, to leave America." And he ends his account of his stay in New York with a tribute to the friends he had made there: "I never thought the name of any place, so far away and so lately known, could ever associate itself in my mind with the crowd of affectionate remembrances that now cluster about it."

No comments:

Post a Comment