Augie gets home to find that strangers have moved into his mother's apartment: Simon has sold the furniture to a Polish family and moved their mother into a room with the Kreindls downstairs. Augie gets another blow when he sees his mother and she tells him of Grandma's death.

He asks Mrs. Kreindl about what made his brother do such a thing, but she's unable to tell him anything useful. He goes to Einhorn's, and on the way meets Coblin and Five Properties, who tell him that Five Properties is getting married. It's Passover, and they try to get him to come with them to a Seder, but Augie hasn't washed after his ordeal on the road, and is eager to see Einhorn to solve the mysteries of what Simon has done.

He's afraid Einhorn is going to chew him out for getting involved with Gorman again, but he doesn't: "I must have looked too sick -- low, gaunt, pushed to an extreme, burned." Einhorn does ask him why he had to bum his way back home: "Your brother told me he was sending you the money to Buffalo." Einhorn had loaned Simon the money for Augie, and made another loan to Simon himself.

Augie's anger at his brother increases with this revelation, and he learns that Simon had got mixed up with a betting pool, and got beat up when things went bad. He wanted the money so he could get married, but Einhorn tells Augie that won't happen now: Five Properties is marrying Simon's girlfriend. And when Simon heard the news, he went to the home of his girlfriend's father, caused a scene, and was thrown in jail. Simon spent one night there and was released when no charges were filed. Einhorn's opinion is that Simon deserved it, but Augie breaks down in tears at the extent of the mess that has been made.

Einhorn gives him a place to stay for the night, and assures him that he'll work something out for his mother. He searches for Simon the next day, but is unable to find him. He meets with Kreindl, who says, "you can see what kind of a man your brother is, that when he gets it in his mind he can sell the goods of the house and put his mother out." Augie assures him that he'll make arrangements for his mother.

He finds a place for his mother at a home for the blind, which costs fifteen dollars a month. He goes to his old room on the South Side and takes his good clothes to a pawnshop, moves his mother to the home, and starts looking for work. Einhorn locates a job with a "luxury dog service," which picks up the pets of wealthy people and takes them to a place where the dogs are "entertained as well as steamed, massaged, manicured, clipped," and are "supposed to be taught manners and tricks." The fee is twenty dollars a month, which as Augie observes, "was more than I had to pay for Mama in the Home." The job is tiring, and at the end of the day he smells so strongly of dog that people move away from him on the streetcar. It also involves going to the homes of people in the class to which he would have belonged if he had agreed to be adopted by the Renlings.Simon continues to elude him, and doesn't answer the messages he leaves for him with his mother and other people.

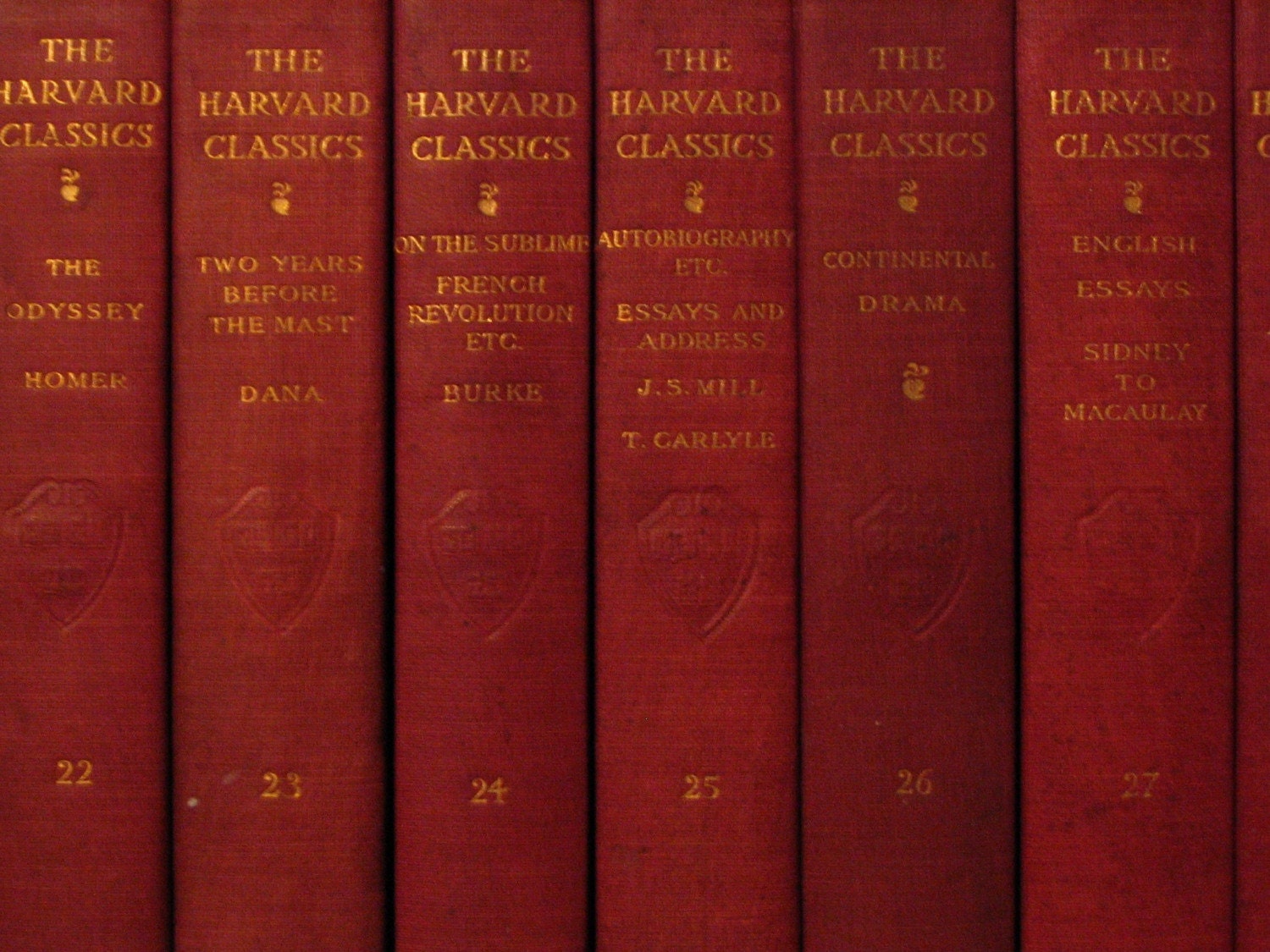

He still has "Dr. Eliot's Five-Foot Shelf," his set of the Harvard Classics that Einhorn had given him after the fire. He is reading Hermann von Helmholtz's On the Conservation of Force one day while waiting for streetcar when a man he had known during his college studies, Manny Padilla, sees him. Padilla had been a whiz in the math class they took together, and is now at the university on a math and physics scholarship. "I wash dogs," Augie tells him.

Padilla tells him he should go back to school: "Don't you see that to do any little thing you have to take an examination, you have to pay a fee and get a card or a diploma?" Augie tells him he doesn't have the money, but Padilla explains that he's "in a racket swiping books," which supplements his tuition scholarship. He takes orders from students for textbooks, steals them from the bookstore, and sells them cheaply. "What's the matter, are you honest?" Padilla asks. Augie replies, "Not completely." Padilla explains that he plans to quit as soon as he can afford it. He goes into bookstores carrying one of his own books, which he puts down on top of the one he wants to steal. Then if he's stopped, he can explain that he absent-mindedly picked up the stolen book with his own. He never hides them in his coat, because that would be hard to explain away.

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Misanthrope, 1598 (Source) |

There's an old, singular, beautiful Netherlands picture I once saw in an Italian gallery, of a wise old man walking in empty fields, pensive, while a thief behind cuts the string of his purse. The old man, in black, thinking probably of God's City, nevertheless has a foolish length of nose and is much too satisfied with his dream. But the peculiarity of the thief is that he is enclosed in a glass ball, and on the glass ball there is a surmounting cross, and it looks like the emperor's symbol of rule. Meaning that it is earthly power that steals while the ridiculous wise are in a dream about this world and the next, and perhaps missing this one, they will have nothing, neither this nor the next, so there is a sharp pain of satire in this amusing thing, and even the painted field does not have too much charm; it is a flat place.So Augie and Padilla become friends and accomplices, even sharing the favors of two black girls of Padilla's acquaintance. And Augie picks up a phrase from Padilla: "Either this stuff comes easy or it doesn't come at all." Augie interprets this to mean, "People were mad to be knocking themselves out over difficulties because they thought difficulty was a sign of the right thing." But Augie also doesn't intend to make larceny his profession: "I didn't mean to settle down to a career of stealing even if it were to come easy, but only to give myself a start at something better."

They decide that Augie will concentrate on books in the humanities, while Padilla continues to filch math texts and technical books. Augie is queasy about his first theft, a copy of Jowett's Plato, but he gets used to it. When he is in a store like Carson Pirie or Marshall Field, he says, "it never entered my mind to branch out and steal other stuff." Soon he is able to quit his dog-club job, but his problem is that he "was struck by the reading fever. I lay in my room and read, feeding on print and pages like a famished man. Sometimes I couldn't give a book up to a customer who had ordered it, and for a long time this was all I could care about."

Padilla is upset when he discovers that Augie is keeping stolen books in his room, and that he holds out on customers until he finishes the books, some of which are very long. He tells Augie he can use his library card and borrow from the library. "But somehow that wasn't the same. As eating hour own meal, I suppose, is different from a handout, even if calory [sic] for calory it's the same value; maybe the body even uses it differently."

I sat and read. I had no eye, ear, or interest for anything else -- that is, for usual, second-order, oatmeal, mere-phenomenal, snarled-shoelace-carfare-laundry-ticket plainness, unspecified dismalness, unknown captivities; the life of despair-harness, or the life of organization-habits which is meant to supplant accidents with calm abiding. Well, now, who can really expect the daily facts to go, toil or prisons to go, oatmeal and laundry tickets and all the rest, and insist that all moments be raised to the greatest importance, demand that everyone breathe the pointy, star-furnished air at its highest difficulty, abolish all brick, vaultlike rooms, all dreariness, and live like prophets or gods? Why, everybody knows this triumphant life can only be periodic. So there's a schism about it, some saying only this triumphant life is real and others that only the daily facts are. For me there was no debate, and I made speed into the former.But then the "daily fact" of Simon reenters his life. Seeing Augie's monastic life allows Simon to assume the upper hand in their relationship when he comes to repay the five dollars he owes Augie. And Augie is unable to follow Einhorn's advice to be hard on his brother. He forgives Simon for not sending the money he needed -- "he'd been in dutch." He forgives him for evicting their mother from the old flat: "we couldn't have kept the old home going much longer and set up a gentle kind of retirement there for Mama, neither of us having that filial tabby dormancy that natural bachelors have." He observes that Simon has grown fat. "However, it wasn't comfortable-looking fat but as if it came from not eating right."

Simon mocks Augie's bookishness: "So you must be in the book business. It can't be much of a business though, because I see you read them too. Leave it to you to find a business like this!" But Augie observes that "there was a dead place where the scorn should have rung." And Simon admits that he hasn't done so well with his life either. He breaks down and admits his mistake in getting mixed up with mobsters, and is filled with regret and disgust at his girlfriend's marrying Five Properties. And he tells Augie that he thought of committing suicide when he spent the night in jail. "This reference to suicide was only factual. Simon didn't work me for pity; he never seemed to require it of me."

But he hedges on the specifics of his current life, telling Augie only that he lives on the Near North Side, and ducking the question of what he's doing for a living. "He had been a fool and done wrong, he showed up sallow and with the smaller disgrace that he was fat, as if overeating were his reply to being crushed -- and with this all over him he wasn't going to tell me, he balked at telling, some small details." But then he says, "I think I'm getting married soon.... To a woman with money." He hasn't even seen her yet, but he thinks, "She's about twenty-two." The marriage is being arranged by his former boss. When Augie says this sounds "cold-blooded," Simon objects: "how can you pretend to me that it makes a difference that Bob loves Mary who marries Jerry? That's for the movies."

Augie stifles the complex of feelings and thoughts that his brother's cynicism arouses in him, and asks why this rich woman wants to marry him. Simon treats it entirely as a business proposition: "Well, first of all we're all handsome men in our family." And, "I'm not marrying a rich girl in order to live on her dough and have a good time. They'll get full value out of me, these people." And, "I have to make money. I'm not one of those guys that give up what they want as soon as they realize they want it. I want money, and I mean want, and I can handle it. Those are my assets. So I couldn't be more on the level with them."

Her name is Charlotte Magnus, he tells Augie, who recognizes Magnus as the name of a coal business. Simon tells him that he's going to ask for a coal yard as a wedding present. And he has come to Augie because he needs a family presence on his side. So Augie agrees to get his good clothes out of hock to play brother of the groom.

No comments:

Post a Comment