Faith: Poetized Religion (Matthew Arnold, George Santayana); Paganized Christianity (D.H. Lawrence, André Gide); Orthodoxy (Paul Claudel)

Faith: Poetized Religion (Matthew Arnold, George Santayana); Paganized Christianity (D.H. Lawrence, André Gide); Orthodoxy (Paul Claudel)_____

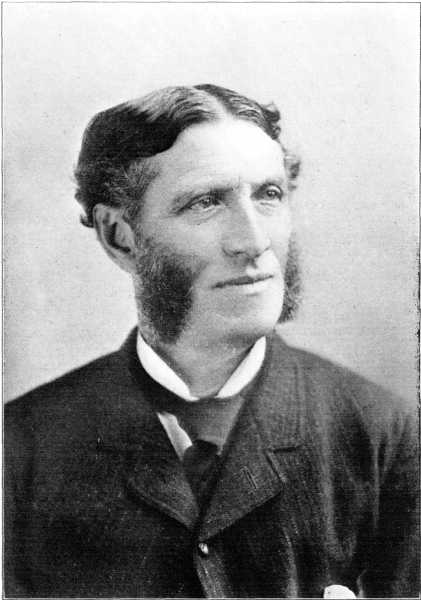

Matthew Arnold: The Finer Spirit of Knowledge

It was an inevitability that with all the challenges to traditional faith, some would come around to the idea that religion, and particularly Christianity, is a product of the imagination just like poetry -- and in fact that the Bible is a great poem with symbolic import if not factual content.

I studied Matthew Arnold, whose 1888 "The Study of Poetry" and 1885 "Literature and Science" are excerpted here, in a "Tennyson, Browning, and Arnold" course in graduate school. Of the three, Tennyson was the most skilled poet, Arnold the most philosophical. And philosophy doesn't usually make for great poetry, as the fact that Arnold's "Dover Beach" is the only one of his poems that still attracts many readers demonstrates. It's a poem about the anxiety brought on by the loss of traditional faith, which Arnold also tackles here:

Our religion has materialised itself in the fact, in the supposed fact; it has attached its emotion to the fact, and now the fact is failing it. But for poetry the idea is everything; the rest is a world of illusion, of divine illusion.So the solution, given the failure of the factual content of religion, is to treat its emotional content the way we treat that of poetry. "More and more mankind will discover that we have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us. Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry."

|

| Matthew Arnold, date unknown |

Arnold looks back to the Age of Faith with some nostalgia: "The mediæval Universities came into being, because the supposed knowledge, delivered by Scripture and the Church, so deeply engages men's hearts, by so simply, easily, and powerfully relating itself to their desire for conduct, their desire for beauty.... The Middle Age could do without humane letters, as it could do without the study of nature, because its supposed knowledge was made to engage its emotions so powerfully." But because of the rise of science, and its challenge to religion, "humane letters," i.e., secular literature, takes a greater role, thanks to its "undeniable power of engaging the emotions." This makes it a partner "to the success of modern science in extirpating what it calls mediæval thinking."

_____

|

| George Santayana, date unknown |

Santayana's "The Poetry of Christian Dogma" (1900) follows Arnold's lead in affirming the role of imaginative creation in finding the way to spiritual truth. St. Paul created "a new poetry, a new ideal, a new God," basing it on "the real experience of humanity." It "was a fable," but "who stopped to question whether its elements were historical, if only its meaning were profound and its inspiration contagious?" Pauline Christianity was "a system complete and consistent within itself." It offered humankind "another world, almost as vast and solid as the real one, in which the soul may develop."

The world of the Christian imagination was eminently a field for moral experience; moral ideas were there objectified into supernatural forces, and instead of being obscured as in the real world by irrational accidents formed an intelligible cosmos, vast, massive, and steadfast.Christianity transcended the demands for empirical verification by virtue of the fact "that all its parts had some significance and poetic truth." Moreover, it triumphed because "its scheme was historical.... It presented a story, not a cosmology. It was an epic in which there was, of course, superhuman machinery, but of which the subject was man, and, notable circumstance, the Hero was a man as well."

Does it matter that it was "just" poetry, that it gave us a false picture of the universe with humankind at its center? Santayana suggests "that what is false in the science of facts may be true in the science of values." (See I.A. Richards on "pseudo-statements.")

While the existence of things must be understood by referring them to their causes, which are mechanical, their functions can only be explained by what is interesting in their results, in other words, by their relation to human nature and to human happiness.Santayana is setting forth the view, essential to existentialism, that we can see things only in human terms. The human center of Christianity, the view of humanity in history, was key to its success over religions such as that of the Greeks and Romans, which saw humankind only as playthings of the superhuman. But Christianity remained a human imaginative construct:

The idea of Christ himself had to be constructed by the imagination in response to moral demands, tradition giving only the barest external points of attachment. The facts sere nothing until they became symbols; and nothing could turn them into symbols except an eager imagination on the watch for all that might embody its dreams.That a god might take human form and die, as Christ did, is "a figure and premonition of the burden of [human] experience." Paul and the Apostles transformed the fact of Jesus's death into "a religious inspiration. The whole of Christian doctrine is thus religious and efficacious only when it becomes poetry, because only then is it the felt counterpart of personal experience and a genuine expansion of human life."

Coda: Wallace Stevens wrote beautifully about Santayana and the transforming imagination in the poem "To an Old Philosopher in Rome."

_____

D.H. Lawrence: The Resurrection of the Body

Lawrence's "The Risen Lord" (1929) follows Santayana in suggesting that the human element is the most powerful force in the story of Christ: "What we have to remember is that the great religious images are only images of our own experiences, or of our own state of mind and soul." But Lawrence pinpoints the changing attitudes toward the story in the experience of World War I, and not in the assaults on the story by the Enlightenment or the Higher Criticism. The wartime experience, or at least the male wartime experience, dethroned the Virgin Mary: "For the man who went through the war the resultant image inevitably was Christ Crucified. And Christ Crucified is essentially womanless."

The problem is, Lawrence says, that the churches don't realize that things have changed: "instead of preaching the Risen Lord, [the churches] go on preaching the Christ-Child and Christ Crucified." And although the men who fought the war recognize the pain and suffering of Christ Crucified, the young, those who did not fight the war, are left with no viable images of Christ.

Now man cannot live without some vision of himself. But still less can he live with a vision that is not true to his inner experience and inner feeling. And the vision of Christ-Child and Christ Crucified are both untrue to the inner experience and feeling of the young.Lawrence insists that for the sake of the young, who find no vision of themselves in the imagery of the church, it should "take the great step onwards, and preach Christ Risen." Lawrence's Christ Risen is Christ in the flesh: "He rises with hands and feet, as Thomas knew for certain: and if with hands and feet, then with lips and stomach and genitals of a man. Christ risen, and risen in the whole of His flesh, not with some left out."

The traditional risen Christ, "floated up into heaven as flesh-and-blood," is false to human experience. The rest of the Christ-story, "The virgin birth, the baptism, the temptation, the teaching, Gethsemane, the betrayal, the crucifixion, the burial and the resurrection, these are all true according to our inward experience." But this bodily ascension doesn't ring true: "Flesh and blood belong to the earth, and only to the earth. We know it."

So instead Lawrence posits a Jesus who remained on earth "in full flesh and soul," who married and had children. "And if He remembered his first life, it would neither be teaching nor preaching, but probably carpentering again, with joy, among the shavings." He would take on the "Roman judges and Jewish priests and money-makers of every sort," and tell them, "I am going to destroy all your values, Mammon, all your money values and conceit values, I am going to destroy them all." He would take on "that which is anti-life, Mammon, like you, and money, and machines, and prostitution, and all that tangled mass of self-importance and greediness and self-conscious conceit which adds up to Mammon."

_____

André Gide: Salvation on Earth

In the excerpts here from his Journals for 1937 and 1916-19, Gide reflects on the ways in which he differs from Nietzsche's attacks on Christianity. Nietzsche "resolutely misunderstands Christ," Gide asserts, and misses the "emancipatory power" of his teachings. Gide thinks Nietzsche mistakes the Church for Christ, and argues that the Church, "by annexing, by trying (in vain moreover) to assimilate Christ, instead of assimilating herself to Him, ... cripples Him more -- and it is this crippled Christ that Nietzsche is fighting."

In his own reading of the Gospels, Gide finds "that it is not so much a question of believing in the words of Christ because Christ is the Son of God as of understanding that he is the Son of God because his word is divine and infinitely above everything that the art of wisdom and man offer us."

It is "the æsthetic truth of the Gospels" to which Gide responds. And because of this he rejects the idea of a blissful afterlife: "It is right now and immediately that we can share in felicity.... One of the gravest misunderstandings of the spirit of Christ comes from the confusion frequently established in the Christian's mind between future life and eternal life." To be born again, Gide argues, is to recognize joy in this life: "Whoever waits for that hour beyond death waits for it in vain. From the very hour at which you are born again, from the very moment at which you drink of this water, you enter the Kingdom of God, you share in eternal life."

_____

Paul Claudel: The Errors of André Gide

|

| Paul Claudel in 1927 |

Catholic and ultraconservative, Claudel was bound to differ with Gide's imaginative reinterpretation of Christianity, as he does in this letter to Gide from 1905. In particular he rejects the view of religion as poetry: "As for what people call 'Art' and 'Beauty,' I had rather that they perished a thousand times over than that we should prefer such creatures to their Creator and the futile construction of our imagination to the reality in which alone we may find delight." Claudel's "reality" is orthodox Christianity.

He also rejects Gide's embrace of nature, which Claudel sees as fallen: "it is in this alone that sanctity consists -- in a filial submission of our will to the Will of our heavenly father. How then can you speak of a pagan sanctity, -- that is to say, of an execrable pride, of the spiritual gormandizing of a creation that has turned in upon itself and revels in its strength and beauty, as if it were itself responsible for their creation?" Paganism is manifested in the decadence of ancient Rome, over which Christianity triumphed. Christianity enjoins "the duties of charity and the duties of justice." And it rejects the power of the wealthy, who on judgment day will be asked, "What have they done with the rare and exceptional gifts which were accorded to them? Were these simply given that they could have a more amusing time? or become artists and dilettantes?"

As for poets and writers like Gide and Claudel:

The mere fact of our enlightenment makes us spread light all about us. We are delegated by the rest of the world to the way of knowledge and truth, and there is no other truth but Christ, who is the Way and the Life, and the duty of knowing and serving Him lies more heavily on us than upon others, and lies upon us with a terrible urgency.

No comments:

Post a Comment