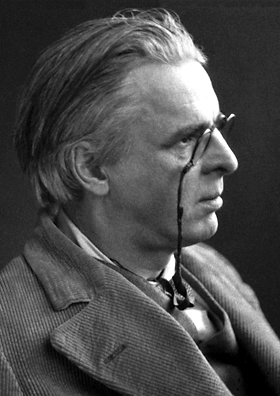

Cultural History: History and Imagination (W.B. Yeats)

Cultural History: History and Imagination (W.B. Yeats)_____

W.B. Yeats: History as Symbolic Reality

How seriously did Yeats really take the elaborate system of cones and gyres that he outlined in the theory of history he set forth in A Vision (written in 1925 and revised in 1937)? As seriously as he took any work of art, which is what the symbolic pattern in the book is: a creation of the artist's imagination working on the data of history. I think the excerpt in this book is overlong, but Ellmann was one of the great Yeats scholars and can be excused for indulging in something he knew quite well.

The system is explained clearly (or as clearly as something so eccentric can be explained) in the editors' note, so I won't attempt to summarize it here. Instead, I'll just comment on some passages that arrested my attention.

A civilisation is a struggle to keep self-control, and in this it is like some great tragic person, some Niobe who must display an almost superhuman will or the cry will not touch our sympathy.Yeats considers history here as a macrocosmic version of the tragic experience in human life. In fact, all of the "organic" theories of history extrapolate from human experience: birth, education, maturity, stasis, decline, death.

Each age unwinds the thread another age had wound, and it amuses one to remember that before Phidias, and his westward-moving art, Persia fell, and that when full moon came round again, amid eastward-moving thought, and brought Byzantine glory, Rome fell; and that at the outset of our westward-moving Renaissance Byzantium fell; all things dying each other's life, living each other's death."All things fall and are built again," Yeats wrote in "Lapis Lazuli." And the image of things being wound and unwound is recurrent, as in poems such as "Byzantium" ("For Hades' bobbin bound in mummy-cloth / May unwind the winding path").

Even before Plato that collective image of man dear to Stoic and Epicurean alike, the moral double of bronze or marble athlete, had been invoked by Anaxagoras when he declared that thought and not the warring opposites created the world. At that sentence the heroic life, passionate fragmentary man, all that had been imagined by great poets and sculptors began to pass away, and instead of seeking noble antagonists, imagination moved towards divine man and the ridiculous devil. Now must sages lure men away from the arms of women because in those arms man becomes a fragment; and all is ready for revelation.Anaxagoras's proclamation that νοῦς, or mind, is the force behind the universe is an anticipation of Schopenhauer's "will." As for the merging of athlete and sage, the assumption that matter and spirit are one necessitates that the perfect embodiment of divinity must itself be perfect.

When revelation comes athlete and sage are merged; the earliest sculptured image of Christ is copied from that of the Apotheosis of Alexander the Great; the tradition is founded which declares even to our own day that Christ alone was exactly six feet high, perfect physical man.

Night will fall upon man's wisdom now that man has been taught that he is nothing. He had discovered, or half-discovered, that the world is round and one of many like it, but now he must believe that the sky is but a tent spread above a level floor, blot out the knowledge or half-knowledge that he has lived many times, and think that all eternity depends upon a moment's decision.For Yeats, beginning his section on "A.D. 1 to A.D. 1050," the "dark ages" were truly dark.

Love is created and preserved by intellectual analysis, for we love only that which is unique, and it belongs to contemplation, not to action, for we would not change that which we love. A lover will admit to a greater beauty than that of his mistress but not its like, and surrenders his days to a delighted laborious study of all her ways and looks, and he pities only if something threatens that which has never been before and can never be again.The desire to preserve beauty runs through all Romantic and post-Romantic poetry, and receives one of its definitive statements in Yeats's "Among School Children," with its familiar final question, "How can we know the dancer from the dance?" -- that is, we can't separate beauty from the process of which it is a part and which eventually takes it away. The beauty of the schoolchildren brings to mind "her" (i.e., Maud Gonne's) former beauty until "Her present image floats into the mind / ... Hollow of cheek as though it drank the wind / And took a mess of shadows for its meat."

The world became Christian, "that fabulous formless darkness," as it seemed to a philosopher of the fourth century, blotted out "every beautiful thing," not through the conversion of crowds or general change of opinion, or through any pressure from below, for civilisation was antithetical still, but by an act of power.The fourth-century philosopher was the neoplatonist Antoninus, and the "act of power" was the legitimizing of the Christian religion by Constantine.

I think that in early Byzantium, maybe never before or since in recorded history, religious, aesthetic and practical life were one, that architect and artificers -- though not, it may be, poets, for language had been the instrument of controversy and must have grown abstract -- spoke to the multitude and the few alike. The painter, the mosaic worker, the worker in gold and silver, the illuminator of sacred books, were almost impersonal, almost perhaps without the consciousness of individual design, absorbed in their subject-matter and that the vision of a whole people. They could copy out of old Gospel books those pictures that seemed as sacred at the text, and yet weave all into a vast design, the work of many that seemed the work of one, that made building, picture, pattern, metal-work of rail and lamp, seem but a single image; and this vision, this proclamation of their invisible master, had the Greek nobility, Satan always the still half-divine Serpent, and never the horned scarecrow of the didactic Middle Ages.This passage is almost a gloss on the two Byzantium poems, and especially on "Sailing to Byzantium," in which the old man, "sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal," wishes to be part of the "vast design" and the "single image" Yeats speaks of above, to transcend process

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

I knew a man once who, seeking for an image of the Absolute, saw one persistent image, a slug, as thought it were suggested to him that Being which is beyond human comprehension is mirrored in the least organised forms of life.Yeats's skepticism about divinity was never more pithily expressed.

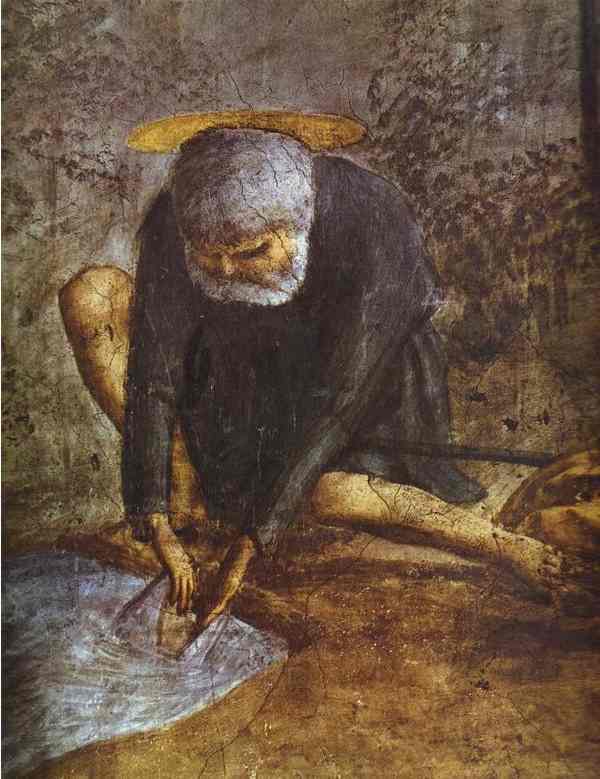

The public certainty that sufficed for Dante and St. Thomas has disappeared, and there is yet no private certainty. Is it that the human mind now longs for solitude, for escape from all that hereditary splendour, and does not know what ails it; or is it that the Image itself encouraged by the new technical method, the flexible brush-stroke instead of the unchanging cube of glass, and wearied of its part in a crowded ghostly dance, longs for a solitary human body? That body comes in the period from 1380 to 1450 and is discovered by Masaccio, and by Chaucer who is partly of the old gyre, and by Villon who is wholly of the new.Art moves from the static and impersonal to the dynamic and personal. Chaucer may be "partly of the old gyre," that is a man of the Middle Ages, but his Canterbury Tales and Troilus and Criseyde celebrate the individually human, not the individual as moral type. Yeats goes on to comment that Masaccio "discovered a naturalism that begins to weary us a little; making the naked young man awaiting baptism shiver with the cold,

St. Peter grow red with the exertion of dragging the money out of the miraculous fish's mouth,

while Adam and Eve, flying before the sword of the Angel, show faces disfigured by their suffering."

It is very likely because I am a poet and not a painter that I feel so much more keenly that suffering of Villon ... in whom the human soul for the first time stands alone before a death ever present in imagination, without help from a Chruch that is fading away; or is it that I remember Aubrey Beardsley, a man of like phase though so different epoch, and so read into Villon's suffering our modern conscience which gathers intensity as we approach the close of an era?Dying of tuberculosis, Beardsley sought to negate his reputation as a producer of "obscene" art by converting to Catholicism and requesting that his more scandalous work be destroyed. (It wasn't.)

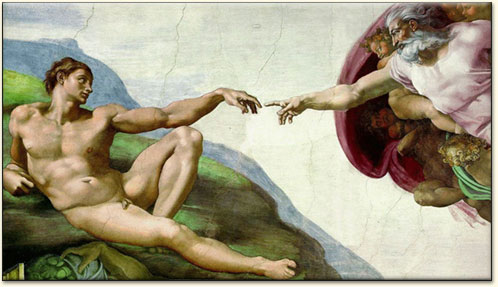

The eighth gyre, which ... completes itself say between 1550 and 1650, begins with Raphael, Michael Angelo and Titian, and the forms, as in Titian, awaken sexual desire -- we had not desired to touch the forms of Botticelli or even of Da Vinci -- or they threaten us like those of Michael Angelo, and the painter himself handles his brush with a conscious facility or exaltation.Although Yeats taxes Titian with making his art too sensuous, in his poems he singled out Michelangelo, and particularly the figure of Adam in the Sistine Chapel. In "Long-Legged Fly":

That girls at puberty may findAnd in "Under Ben Bulben":

The first Adam in their thought,

Shut the door of the Pope's chapel,

Keep those children out.

Michael Angelo left a proof"Profane" acknowledges that the specifically religious content of Michelangelo's art is secondary.

On the Sistine Chapel roof,

Where but half-awakened Adam

Can disturb globe-trotting Madam

Till her bowels are in heat,

Proof that there's a purpose set

Before the secret working mind:

Profane perfection of mankind.

Shakespeare represents the next step toward the fully secular role of art, as well as what Harold Bloom calls "the invention of the human":

I see in Shakespeare a man in whom human personality, hitherto restrained by its dependence upon Christendom or by its own need for self-control, burst like a shell. Perhaps secular intellect, setting itself free after five hundred years of struggle, has made him the greatest of dramatists, and yet ... we might, had the total works of Sophocles survived -- they too born of a like struggle though with a different enemy -- not think him the greatest. Do we not feel an unrest like that of travel itself when we watch those personages, more living than ourselves, ... when we are carried from Rome to Venice, from Egypt to Saxon England, or in the one play from Roman to Christian mythology?Milton, however, strikes Yeats as a man betrayed by his moment in history, too late for the kind of synthesis of the sacred and profane that Michelangelo succeeded in accomplishing. The result is "his unreality and his cold rhetoric." In "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity," "his classical mythology is an artificial ornament." Christian humanism has become passé.

By the end of the eighteenth century,

Personality is everywhere spreading out its fingers in vain, or grasping with an always more convulsive grasp a world where the predominance of physical science, of finance and economics in all their forms, of democratic politics, of vast populations, of architecture where styles jostle with one another, of newspapers where all is heterogeneous, show that mechanical force will in a moment become supreme.

Locke sank into a swoon;The rise of the novel takes us into the age of mass man:

The Garden died;

God took the spinning-jenny

Out of his side.

Dickens was able with a single book, Pickwick, to substitute for Jane Austen's privileged and perilous research the camaraderie of the inn parlour, qualities that every man might hope to possess, and it did not return till Henry James began to write.And in the absence of a unifying, all-encompassing spiritual belief,

there came synthesis for its own sake, organisation where there is no masterful director, books where the author has disappeared, painting where some accomplished brush paints with an equal pleasure, or with a bored impartiality, the human form or an old bottle, dirty weather and clean sunshine. I too think of famous works where synthesis has been carried to the utmost limit possible, where there are elements of inconsequence or discovery of hitherto ignored ugliness, and I notice that when the limit is approached or past, when the moment of surrender is reached, when the new gyre begins to stir, I am filled with excitement. I think of recent mathematical research; even the ignorant can compare it with that of Newton ... with its objective world intelligible to intellect; I can recognise that the limit itself has become a new dimension, that this every-hidden thing which makes us fold our hands has begun to press down upon multitudes. Having bruised their hands upon that limit, men, for the first time since the seventeenth century, see the world as an object of contemplation, not as something to be remade, and some few, meeting the limit in their special study, even doubt if there is any common experience, doubt the possibility of science.

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

No comments:

Post a Comment