____

It's probably worth repeating that Dickens heavily fictionalizes the circumstances of the Gordon riots, including the fact that the Catholic emancipation laws had already been passed. In the novel, the Protestant Alliance is trying to prevent their passage. And although Gordon himself was an actual figure, Gashford is fictional -- Gordon's real secretary was James Fisher. And Gordon's servant was named James M'Queen, not John Grueby. To an age that has never heard of the Gordon riots, the point is probably moot anyway.Dickens proceeds to depict Gashford as a sinister, Svengali-like figure -- "his countenance ... was singularly repulsive and malicious" and his brow, naturally, is "beetling" and his lip "curled" as he goes to find out if Gordon has been sleeping. And Gordon continues to act as if he doesn't quite know what's going on, asking for reassurance that they are "really forty thousand strong" or are just rounding up. Gashford proceeds to enumerate their supporters, including "Dennis the hangman" and the president of the United Bulldogs, one "Mr Simon Tappertit," whom Gordon recalls as "The little man, who sometimes brings an elderly sister to our meetings, and sometimes another female too, who is conscientious, I have no doubt, but not well-favoured." Gashford identifies the "elderly sister" and Mrs. Varden and the "tall spare female" as Miggs, but notes that Mr. Varden hasn't joined up: "A malignant ... Unworthy such a wife. he remains in outer darkness and steadily refuses."

After an outburst of enthusiasm in which he vows his devotion to the cause "for this unhappy country's sake" -- "springing up in bed, after repeating the phrase 'unhappy country's sake' to himself, at least a dozen times" -- Gordon falls asleep. Dickens proceeds to comment:

Although there was something very ludicrous in his vehement manner, taken in conjunction with his meagre aspect and ungraceful presence, it would scarcely have provoked a smile in any man of kindly feeling.... This lord was sincere in his violence and in his wavering. A nature prone to false enthusiasm, and the vanity of being a leader, were the worst qualities apparent in his composition. The rest was weakness -- sheer weakness.After Gordon falls asleep, Gashford takes two "printed handbills" from a secret compartment in a trunk, slips one under the entrance door of the Maypole and wraps the other around a stone and tosses it from the window. The handbills are designed to attract followers, and whoever finds one is urged to pass it along.

Dickens now begins to preach a bit:

To surround anything, however monstrous or ridiculous, with an air of mystery, is to invest it with a secret charm, and power of attraction which to the crowd is irresistible. False priests, false prophets, false doctors, false patriots, false prodigies of every kind, veiling their proceedings in mystery, have always addressed themselves at an immense advantage to the popular credulity, and have been, perhaps, more indebted to that resource in gaining and keeping for a time the upper hand of Truth and Common Sense, than to any half-dozen items in the whole catalogue of imposture. Curiosity is, and has been from the creation of the world, a master-passion.But much of his sermon is still distressingly relevant, for he certainly doesn't underestimate the power to manipulate what he calls "the unthinking portion of mankind." Gordon's aim, to persuade Parliament not to remove "the penal laws against Roman Catholic priests, the penalty for educating children in the Catholic faith, and the restrictions on inheritance of property by Catholics, might have gained some intellectual assent. But it was the power of rumor that Gordon played on: that "a secret power was mustering against the government for undefined and mighty purposes," that the "Popish powers" were planning "to degrade and enslave England, establish an inquisition in London, and turn the pens of Smithfield market into stakes and cauldrons" for torturing and executing Protestants. The whisper campaign, aided by the surreptitiously distributed fliers and pamphlets, played on fear, so "the mania spread indeed, and the body, still increasing every day, grew forty thousand strong."

The persistence of ignorance and intellectual sloth still allows politicians and their backers to make people credit their claims of "death panels" in the health care bill, or to stir the strange fear that somehow "Sharia law" is going to be imposed in the United States. As for Gordon's threat of Popery and his claim of a massing resistance to Catholic emancipation, "Whether it was the fact or otherwise, few man knew or cared to ascertain." So "he and his proceedings beg[a]n to force themselves ... upon the notice of thousands of people, ... who, without being deaf or blind to passing events, had scarcely ever thought of him before."

Dickens's Gordon is an unlikely leader for such a movement, being a simpleton easily manipulated by Gashford. He wakes from his sleep and doesn't remember where he is, but tells Gashford that he "dreamed that we were Jews.... You and I -- both of us -- Jews with long beards." (The actual Gordon converted to Judaism in 1787.) Gashford replies, "Heaven forbid, my lord! We might as well be Papists." Gashford is unable to get Gordon to focus his attention until he picks up Gordon's watch and reads the inscription on it: "Called, and chosen, and faithful." It seems to work a kind of hypnotic spell on Gordon, for "as the words were uttered, Lord George, who had been going on impetuously, stopped short, reddened, and was silent."

Gashford is then able to get Gordon focused on the work of the day, and he tells him that expects "One or two recruits" from the fliers he left last night. This brings Gordon around to urge, "We must be up and doing!" and he quickly gets ready for their departure from the Maypole. Gashford is not so swift to get ready:

--"Dreamed he was a Jew," he said thoughtfully, as he closed the bedroom door. "He may come to that before he dies. It's like enough. Well! After a time, and provided I lost nothing by it, I don't see why that religion shouldn't suit me as well as any other. There are rich men among the Jews; shaving is very troublesome; -- yes, it would suit me well enough. For the present, though, we must be Christian to the core."

|

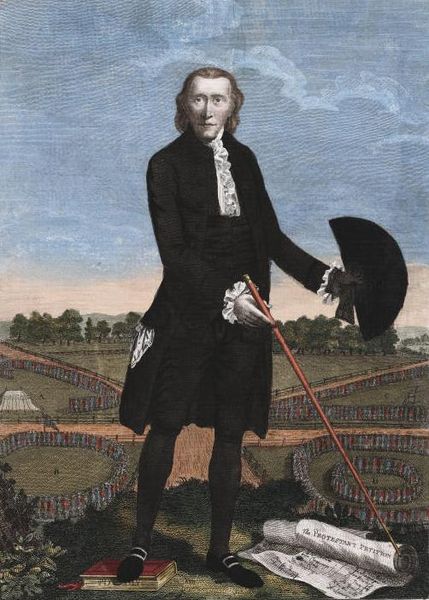

| Lord George Gordon in 1780 |

That afternoon, Gashford is visited by Ned Dennis, "a squat, thickset personage, with a low, retreating forehead, a coarse shock head of hair, and eyes so small and near together, that his broken nose alone seemed to prevent their meeting and fusing into one of the usual size.... in his grimy hands he held a knotted stick, the knob of which was carved into a rough likeness of his own face." (A note informs us that the actual Edward Dennis, the public hangman, didn't resemble Dickens's description.) Gashford and Dennis discuss the latter's work as hangman, Gashford answering in the affirmative Dennis's question: "My work, is sound, Protestant, constitutional, English work. Is it, or is it not?" He prides himself on the number of people he has hanged, noting that he would have hanged more if George III hadn't decided to give the condemned the option of enlisting in the army or navy. He supports the Protestant Association, he tells Gashford, because, "If these Papists gets into power, and begins to boil and roast instead of hang, what becomes of my work! ... I mustn't have no biling, no roasting, no frying -- nothing but hanging."

Gashford tells Dennis that next month, or perhaps in May, they will "convene our whole body for the first time. My lord has thoughts of our walking in procession through the streets -- just as an innocent display of strength -- and accompanying our petition down to the door of the House of Commons." They will be of such numbers that they will need to be divided into groups and "Lord George has thought of you as an excellent leader for one of these parties." Dennis agrees.

Grueby then enters to tell Gashford "here's another Protestant," but although Gashford says he can't see him now, the man walks in anyway. It is Hugh.

Gashford recognizes Hugh from the Maypole and tells Grueby that it's okay. Hugh then hands Gashford one of the handbills he had dropped there. "I want to make one against the Catholics, I'm a No Popery man, and ready to be sworn in. That's what I've come here for." Dennis says, "No Popery, brother!" and Hugh replies, "No Property, brother!" Gashford corrects him -- "Popery, Popery" -- but Dennis says, "It's all the same!" He also examines Hugh and observes, "Do but cast your eye upon it. There's a neck for stretching, Muster Gashford!" He is also delighted to hear that Hugh can't read or write, "those two arts being (as Mr Dennis swore) the greatest possible curse a civilised community could know, ... militating ... agasint the professional emoluments and usefulness of the great constitutional office he had the honour to hold."

After Gashford welcomes Hugh to the Protestant Association, Hugh and Dennis walk out together, and when they reach Westminster, Dennis points out to him the weaknesses of the building where the houses of Parliament met "and how plainly, when they marched down there in great array, their roars and shouts would be heard by the members inside; with a great deal more to the same purpose, all of which Hugh received with manifest delight." He points out to Hugh several of the members of Parliament, and tells him which are favorable to their cause and which aren't. There are others there for the same purpose, always in groups of two or three, but they don't speak to others outside their group. But occasionally a paper is passed from one group to another, but so quickly that Hugh is unable to see who is handing it out. "They often trod upon a paper like the one he carried in his breast, but his companion whispered him not to touch it or to take it up, -- not even to look towards it."

Dennis then suggests that they go to The Boot, a pub "in the fields at the back of the Foundling Hospital; a very solitary spot at that period." Hugh recognizes many of the people he had seen in the crowd at Westminster, and Dennis proclaims a toast to "the health of Lord George Gordon, President of the Great Protestant Association; which toast Hugh pledged likewise." A fiddler strikes up a tune and Hugh and Dennis perform "an extemporaneous No-Popery Dance."

Then Sim Tappertit arrives with two other members of the United Bulldogs, one of whom is Mark Gilbert, whom we saw initiated into the erstwhile 'Prentice Knights. Like Sim, the other two are no longer apprentices but journeymen. Sim is acquainted with Dennis, who informs him that Hugh has joined their movement. Sim realizes then that he has seen Hugh before, and asks him "Did you ever see me before? You wouldn't be likely to forget it, you know, if you ever did." Hugh confesses that he doesn't recognize Sim, which annoys Sim very much. Then Sim recognizes that Hugh was once "hostler at the Maypole." He tells Hugh that he visited there "to ask after a vagabond that had bolted off.... Don't you remember my thinking you liked the vagabond, and on that account going to quarrel with you; and then finding you detested him worse than poison, going to drink with you?" This refreshes Hugh's memory, and he becomes great friends with Sim.

"The bare fact of being patronised by a great man whom he could have crushed with one hand, appeared in his eyes so eccentric and humorous, that a kind of ferocious merriment gained the mastery over him, and quite subdued his brutal nature." When Sim gets up on a barrel to deliver a speech against Popery, Hugh stands beside him, "and though he grinned from ear to ear at every word he said, threw out such expressive hints to scoffers in the management of his cudgel, that those who were at first the most disposed to interrupt, became remarkably attentive, and were the loudest in their approbation."

At the other end of the room, there's a group of men "in earnest conversation all the time; and when any of this group went out, fresh people were sure to come in soon afterwards and sit down in their places, as though the others had relieved them on some watch or duty; which it was pretty clear they did, for these changes took place by the clock, at intervals of half an hour." They have a collection of newspapers and read articles aloud in a low voice from them. "But the great attraction was a pamphlet called The Thunderer, which espoused their own opinions, and was supposed at that time to emanate directly from the Association.... It was impossible to discard a sense that something serious was going on, and that under the noisy revel of the public-house, there lurked unseen and dangerous matter."

Sim, meanwhile, is trying to find out what Dennis's line of work is, but the hangman remains coy about it, though he puts "his fingers with an absent air on Hugh's throat, and particularly under his left ear, as if he were studying the anatomical development of that part of his frame." This leads Sim to guess that Dennis is "a kind of artist," which Dennis enthusiastically agrees to. Sim notices the portrait carved on top of Dennis's stick, which turns out to have been done by one of his victims, although Dennis circumlocutes his way around this revelation. He was there the morning he died, he admits. "He wouldn't have gone off half as comfortable without me. I had been with three or four of his family under the same circumstances." Then he comments that every item of clothing he is wearing "belonged to a friend of mine that's left off sich incumbrances for ever."

When they leave The Boot, Hugh accompanies Sim until he remembers that he has somewhere to go, leaving Sim to imagine his new friend's role in a revolutionary future:

"In an altered state of society -- which must ensue if we break out and are victorious -- when the locksmith's child is mine, Miggs must be got rid of somehow, or she'll poison the tea-kettle one evening when I'm out. He might marry Miggs, if he was drunk enough. It shall be done. I'll make a note of it."

No comments:

Post a Comment