_____

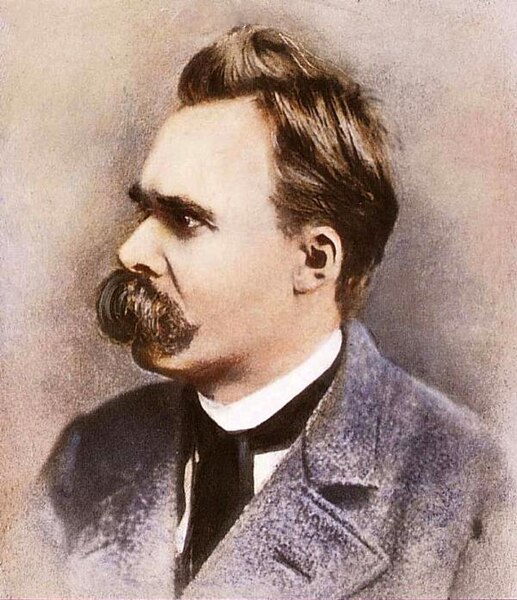

Friedrich Nietzsche: The Acceptance of Untruth

For help with these excerpts from The Joyful Wisdom and The Antichrist, I need to turn to Ellmann and Feidelson's introduction again:

|

| Friedrich Nietzsche, date unknown |

Another face of poetic inconclusiveness and non-assertion is poetic affirmation, which is equally indifferent to objective tests of truth [as Richards's "pseudo-statements"]. Nietzsche finds that "untruth" is a condition of life; opinions, ideas, and beliefs are unavoidably false, yet they are necessary to gauge reality against imagined standards without which life would be arid. Affirmations, however fictional, are life-furthering because they extend man's sway over things and also provide necessary food for the passions, which crave attachments. Consequently skeptics, including Zarathustra himself, employ convictions as expressive material.In Nietzsche's view, we have art to thank for making us used to untrue things, otherwise "the insight into the general untruth and falsity of things now given us by science -- an insight into delusion and error as conditions of intelligent and sentient existence -- would be quite unendurable." Existence itself has now become "an aesthetic phenomenon," and we should relish the fact that we are all fools content with illusions: "we must now and then be joyful in our folly, that we may continue to be joyful in our wisdom!" Art gives us this joy: "we need all arrogant, soaring, dancing, mocking, childish and blessed Art, in order not to lose the free dominion over things which our ideal demands of us."

We should also celebrate our liberation from dogma. "Strength, freedom which is born of the strength and overstrength of the spirit, proves itself by skepticism.... Convictions are prisons.... Freedom from all kinds of convictions, to be able to see freely, is part of strength."

W.B. Yeats: The Conquest of Scepticism

Skepticism can only take us so far, Yeats argued in his journal in 1929. He cites Ezra Pound's contention "that we know nothing but sequences. 'If I touch the button the electric lamp will light up -- all our knowledge is like that.'" Yeats argues that this may be scientifically accurate, but philosophically false. Skepticism "is mere acknowledgement of a limit." To affirm something that may be verifiably untrue from the skeptical point of view may nevertheless prove useful: "I have felt when re-writing every poem ... that by assuming a self of past years, as remote from that of today as some dramatic creation, I touched a stronger passion, a greater confidence than I possess, or ever did possess." Pound, he says, does the same thing when he writes his imitations of Propertius or the Chinese poets: he "escapes his scepticism." It's not that we believe when we imagine things, it's that we put ourselves in the same state of mind as if we believed, with the same result. We accept the power of tradition when we do so. "The 'modern man' is a term invented by modern poetry to dignify our scepticism."

Charles Baudelaire: The Didactic Heresy

It was Théophile Gautier who took for his slogan the phrase "l'art pour l'art," which we know as "art for art's sake" (or as the MGM slogan Ars gratia artis, coined by some studio publicist with a smattering of Latin). And the Baudelaire selection is from his 1861 essay on Gautier, a defense of that poet's doctrine. Naturally, the corollary to the premise that art is an end in itself is that art must not sacrifice its integrity for the sake of teaching or preaching. So Baudelaire insists, "Poetry ... has no object but itself: it can have no other, and no poem will be so great, so noble, so truly worthy of the name of poem as that which has been written solely for the pleasure of writing a poem." There is a wee bit of a desire to shock in the statement, and both its message and the tone in which it is delivered clearly influenced Oscar Wilde's pronouncements on the same topic. When Baudelaire says, "I say that if the poet has pursued a moral end, he has diminished his poetical power," he's saying the same thing we've already seen Wilde say (except that Wilde said it more wittily).

Oscar Wilde: The Improvidence of Art

And Wilde says it again in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray thirty years after Baudelaire's essay on Gautier. He continues to try to shock, when he claims, "No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style." Well, obviously artists do have "ethical sympathies," but the point is that they shouldn't let them show -- at least not blatantly."

The central point in Wilde's preface, I think, the one that links him with so many others in this section of the anthology, is, "From the point of view of form, the type of all the arts is the art of the musician." In music, form and content are the same thing, which is the ideal toward which Wilde and his contemporaries repeatedly claimed to strive. But Wilde also adds, "From the point of view of feeling, the actor's craft is the type." The actor may or may not actually feel what the character he plays is feeling, but he is judged only by how successfully he makes the audience believe that he does. Sincerity is not in question, or as the cynical saying goes, "If you can fake that, you've got it made."

And then there's this knotty sequence of epigrams:

If we equate "surface" with "form," and "symbol" with "content," we oversimplify what Wilde is saying, but it may help us get closer to his meaning. It is really an echo of the two statements made earlier in the preface:All art is at once surface and symbol.Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.

The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.For Caliban, the untutored savage, read "bourgeois philistine," who chafes at both the realistic artist's candor and the romantic artist's idealizations.

The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

And finally: "All art is quite useless." Which only means that art that can be used to point a moral, adorn a tale, elect a candidate, promote a dogma, and so on, isn't really art.

Richard Wagner: Literature as Music-Drama

|

| Richard Wagner, c. 1862 |

He begins with some nationalistic reflections on the "peculiar significance of German efforts in art," which are characteristic of Wagner but nevertheless a little embarrassing today. But he finally settles down to the aesthetics of the matter, the pre-eminence of "music, that language intelligible to all men." He asserts that "the special, separately developed branches of art, however much their capabilities of expression might finally be brought out and heightened by great geniuses, nevertheless, without falling into unnaturalness and decided error, could never aim to supply in any way that all-powerful work of art which was only possible through a union of their forces."

Each artistic medium, he asserts, runs the risk of developing itself to its limits, "and that it cannot pass these limits without the danger of losing itself in the unintelligible and absolutely fantastic -- even in the absurd." (Some would say that literature passed these limits with Finnegans Wake, or painting with the exhibition of perfectly white canvases, or even music, with John Cage's 4'33" -- four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence.) Wagner's solution to the problem of limits is for the media to join forces. And particularly for poetry and music to collaborate. He began "to see in the opera an ideal branch of art."

The poet seeks, in his language, to make the abstract, conventional meaning of words subordinate to their original, sensible one; and to secure, by rhythmic order, as well as by the almost musical dressing of words in versification, an effect for his phraseology which shall gain possession of and influence the feelings as though by enchantment.For Wagner, Beethoven is chief among his predecessors for having, through the symphony, achieved a kind of drama, "a language of which no one in any preceding age had any knowledge, inasmuch as the pure musical expression in it enchains the hearer with a lasting effect hitherto unknown." He speculates that human language "developed from a purely sensuous, subjectively-felt signification of words, into a more abstract sense" that eventually robbed words of feeling "and made their very connection and construction entirely dependent on certain rules that could be learned." (Very few language experts would agree.) So he sees only two paths open for the development of poetry: either into pure abstraction as a vehicle for philosophy, or "it must become intimately bound up with music, and with such music as that whose endless power is revealed to us by the symphony of Beethoven."

In this course of the poet, so necessary to his very nature, we see him finally come to the limits of his branch of art, where it already seems to touch music, and thus the most successful work of the poet must be, for us, that which should be, in its perfection, entirely musical.

And for the poet, "no poetic form is fitted for his use but that in which the poet no longer describes, but brings his subject into actual representation, that is convincing to the senses; -- and this form is nothing but -- the drama," which "awakens in the spectator real participation in the action presented to him."

Stéphane Mallarmé: Poetry as Incantation

|

| Stéphane Mallarmé, 1896 |

But language is not music:

It's that old duality of sound and sense again. So he welcomes Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk: "We now hear undeniable rays of light, like arrows gilding and piercing the meanderings of son. I mean that, since Wagner appeared, Music and Verse have combined to form Poetry."I am disappointed when I consider how impossible it is for language to express things by means of certain keys which would reproduce their brilliance and aura.... When compared to the opacity of the word ombre, the word ténèbres does not seem very dark; and how frustrating the perverseness and contradiction which lend dark tones to jour, bright tones to nuit! We dream of words brilliant at once in meaning and sound, or darkening in meaning and so in sound, luminously and elementally self-succeeding. But, let us remember that if our dream were fulfilled, verse would not exist -- verse which, in all its wisdom, atones for the sins of languages, comes nobly to their aid.

The one thing that poets must now begin to avoid in their verse is description, "that erroneous esthetic ... which would have the poet fill the delicate pages of his book with the actual and palpable wood of trees, rather than with the forest's shuddering or the silent scattering of thunder through the foliage." Instead of description the poet should rely on "evocation, allusion, suggestion." Poetry that too directly confronts reality risks didacticism and loses its special role: "Speech is no more than a commercial approach to realisty. In literature, allusion is sufficient: essences are distilled and then embodied in Idea."

In Wilde's preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, he asserted, "To reveal art and conceal the artist is art's aim." Mallarmé makes a similar assertion: "If the poem is to be pure, the poet's voice must be stilled and the initiative taken by the words themselves, which will be set in motion as they meet unequally in collision." Pure poetry is the aim, as in Mallarmé's own poem, "Le tombeau d'Edgar Poe," which lauds the attempt to "purify the words of the tribe": "Donner un sens plus pur aux mots de la tribu."

Where Wagner would give priority to music, Mallarmé would substitute language. "For, undeniably, the true source of Music must not be the elemental sound of brasses, strings, or wood winds, but the intellectual and written word in all its glory -- Music of perfect fulness and clarity, the totality of universal relationships." Like Richards, Mallarmé distinguishes between something like statements and pseudo-statements, dividing words "into two different categories: first, for vulgar or immediate, second, for essential purposes. The first is for narrative, instruction, or description.... Language, in the hands of the mob, leads to the same facility and directness as does money. But, in the Poet's hands, it is turned, above all, to dream and song."

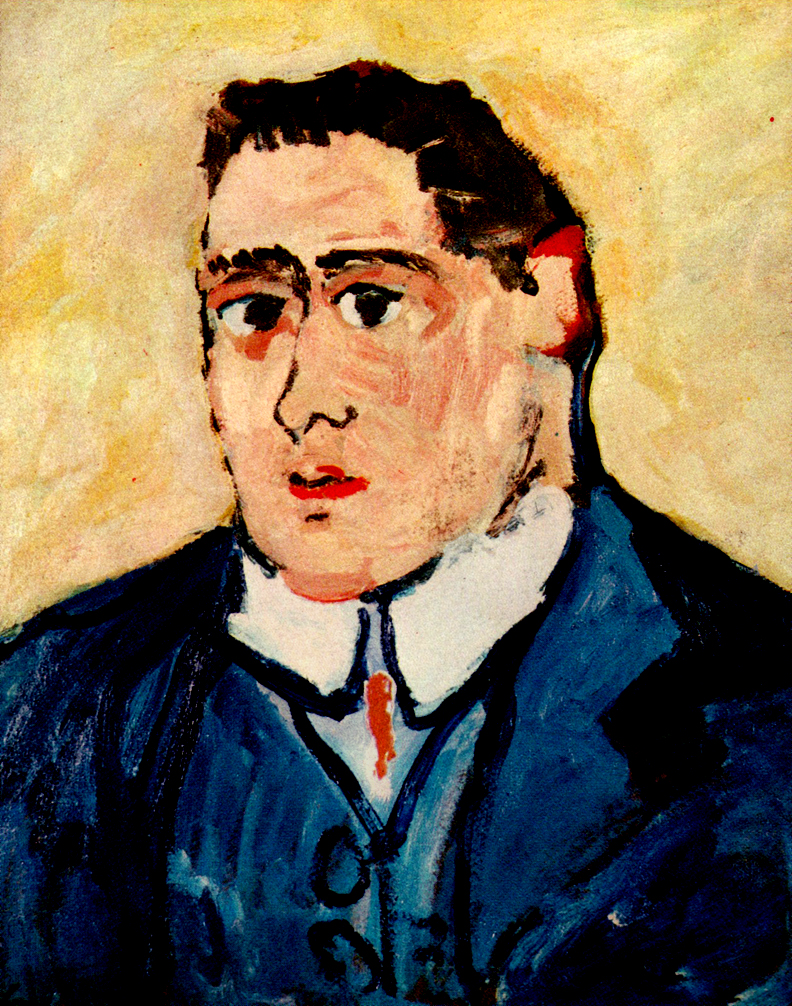

Guillaume Apollinaire: Pure Painting

|

| Maurice Vlaminck, Guillaume Apollinaire, 1903 |

Flame is the symbol of painting, and the three plastic virtues burn with radiance.

He argues that the more a painting exists on its own terms, insists on its own integrity, the more it participates in the eternal: "We will not go astray in the unknown future, which, severed from eternity, is but a word fated to tempt man. We will not waste our strength on the too fugitive present; the fashionable, for the artist, can only be the mask of death." And of course, the artist must resemble God the Creator: "Each god creates in his own image, and so do painters. Only photographers manufacture duplicates of nature." (Howls of protest from photographers.)

Flame has a purity which tolerates nothing alien, and cruelly transforms in its image whatever it touches.

Flame has a magical unity; if it is divided, each fork will be like the single flame.

Finally it has the sublime and incontestable truth of its own light.

Like Mallarmé, he rejects the descriptive, or in painterly terms, the representational: "Real resemblance no longer has any importance, since everything is sacrificed by the artist to truth, to the necessities of a higher nature whose existence he assumes but does not lay bare. The subject has little or no importance any more.... While the goal of painting is today, as always, the pleasure of the eye, the art-lover is henceforth asked to expect delights other than those which looking at natural objects can easily provide."

Once again, music is the norm: "we are moving towards an entirely new art which will stand, with respect to painting ... as music stands to literature. It will be pure painting, just as music is pure literature." At the basis of pure painting is mathematics: "geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of the writer." Unlike the Greeks, who "took man as the measure of perfection, ... the art of the new painters takes the infinite universe as its ideal."

Once again, we are told, essentially, that Nature imitates Art: "It is the social function of great poets and artists to renew continually the appearance nature has for the eyes of men. Without poets, without artists, men would soon weary of nature's monotony... The order which we find in nature, and which is only an effect of art, would at once vanish. Everything would break up in chaos."

|

| Pablo Picasso, Houses on the Hill, Hora de Ebro, 1909 |

He turns to a particular school of painting, Cubism, which he says is "a name first applied to it in the fall of 1908 in a spirit of derision by Henri Matisse, who had just seen a picture of some houses, whose cube-like appearance had greatly struck him." (Perhaps the Picasso painting above, dated a year later.) "Cubism differs from the old schools of painting in that it aims, not at an art of imitation, but at an art of conception, which tends to rise to the height of creation." Apollinaire distinguishes several subsets of Cubism, and concludes, "I love the art of today because above all else I love the light, for man loves light more than anything; it was he who invented fire."

Marcel Duchamp: The Non-Picture

|

| Marcel Duchamp 1950. © Jacqueline Matisse Monnier |

Duchamp's suggestion that we substitute the word "delay" for "painting" or "picture" is not merely the great surrealist's whimsy. It in fact acknowledges the independence of the work itself, that its significance exists in the encounter with a viewer, who is "delayed" by his or her contemplation of the work. It acknowledges all of the themes we have been covering: the independence of the artwork from intellectual correlatives, its purity, its existence in time and outside of it.

Duchamp, of course, is famous for teasing the viewer into contemplation of what is or isn't a work of art. Is a urinal labeled "A Fountain" a work of art or a silly joke? Is Mona Lisa with a mustache (and an obscene pun for a title) a work of art or a desecration of a masterpiece? Discuss.

| |||

| Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 |

|

| Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., 1919 |

No comments:

Post a Comment