_____

Oscar Wilde: The Priority of ArtIn this excerpt from the dialogue "The Decay of Lying," Cyril and Vivian discuss the relationship between Art and Nature.

Anyone can come up with paradoxes, but Wilde is one of the few who can make them not only clever but also wise. Vivian rattles them off here in a run of seemingly glib antitheses:

the more we study Art, the less we care for Nature

...

Art is our spirited protest, our gallant attempt to teach Nature her proper place.

...

The ancient historians gave us delightful fiction in the form of fact; the modern novelist presents us with dull facts under the guise of fiction.

...

Many a young man starts in life with a natural gift for exaggeration which, if nurtured in congenial and sympathetic surroundings, or by the imitation of the best models, might grow into something really great and wonderful. But, as a rule, he comes to nothing.... He either falls into careless habits of accuracy, or takes to frequenting the society of the aged and the well-informed.

...

[He] often ends by writing novels which are so life-like that no one can possibly believe in their probability.

...

Wordsworth ... found in stones the sermons he had already hidden there.

And finally:

Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life.

|

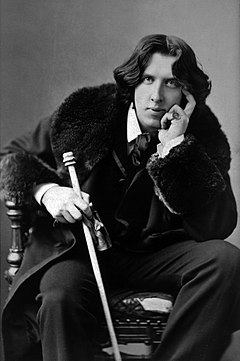

| Oscar Wilde in 1882 |

|

| Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533 |

|

| Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I of England, c. 1635 |

|

| James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge, c 1872-75 |

|

| J.M.W. Turner, Sunset, 1830-35 |

- "Art never expresses anything but itself."

- "All bad art comes from returning to Life and Nature, and elevating them into ideals.... The moment Art surrenders its imaginative medium it surrenders everything.... Life goes faster than Realism, but Romanticism is always in front of Life."

- "Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life."

- "Lying, the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of Art."

Rainer Maria Rilke: The Unnatural Will to Art

|

| Rainer Maria Rilke, c. 1900 |

This excerpt is from a letter written by Rilke in 1920 to his lover, Baladine Klossowska, whom he called "Merline." He speaks in it of his "struggle towards concentration," his attempt to touch his "center of production" and to find the "purest impulse" and to "recreate [the] first innocence" at which "the Angel discovered you when he brought you the first binding message." In short, to become open to the traditional moment of inspiration. But what is less traditional is essentially a paraphrase of what Wilde asserted above. Rilke puts it this way: "Art, as I conceive it, is a movement contrary to nature."

And to go against nature is of necessity a struggle. We artists, he asserts, must "throw ourselves into the abyss of our being." This is a form of self-immolation: "If the meaning of sacrifice is that the moment of greatest danger coincides with that when one is saved, then certainly nothing resembles sacrifice more than this terrible will to Art." Most humans try to forget things to survive, but artists "are always bent on discovering, on magnifying even" the things that others strive to forget: "it is we who are the real awakeners of our monsters, to which we are not hostile enough to become their conquerors; for in a certain sense we are at one with them" -- they supply the strength that the artist needs. It's not a question of conquest at all: "it is not for us to consider ourselves the tamers of our internal lions. But suddenly we feel ourselves walking beside them, as in a Triumph, without being able to remember the exact moment when this inconceivable reconciliation took place (bridge barely curved that connects the terrible with the tender ... )"

That ravishing parenthetical phrase and the artist's role as creator ex nihilo brings to mind one of Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus:

O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt.

O this is the animal that does not exist.

Sie wußtens nicht und habens jeden Falls

But they didn't know that, and, in any case,

-- sein Wandeln, seine Haltung, seinen Hals,

they loved it -- loved its gait, its stance,

bis in des stillen Blickes Licht -- geliebt.

its neck, loved the light in its quiet gaze.

Zwar war es nicht. Doch weil sie's liebten, ward

It never was. But since they loved it,

ein reines Tier. Sie ließen immer Raum.

a pure animal became. They always left space.

Und in dem Raume, klar und ausgespart,

And in that space, unoccupied and bright,

erhob es leicht sein Haupt und brauchte kaum

it calmly raised its head and scarcely needed

zu sein. Sie nährten es mit keinem Korn,

to be. They fed it not with grain, --

nur immer mit der Möglichkeit, es sei.

only with the promise of its being.

Und die gab solche Stärke an das Tier,

And this gave the animal such power,

daß es aus sich ein Stirnhorn trieb. Ein Horn.

that a horn sprouted from its brow. One horn.

Zu einer Jungfrau kam es weiß herbei --

White, it strode up to a virgin -- and was,

und war im Silber-Spiegel und in ihr.

in the mirror's silver and in her.

Translation by Edward Snow

Pablo Picasso: Art as Individual Idea

|

| Pablo Picasso, date unknown |

In this essay from 1923, Picasso aligns himself with the Romantic idea of spontaneity, and with art as a serendipitous pursuit: "When I paint my object is to show what I have found and not what I am looking for.... What one does is what counts and not what one had the intention of doing." And he, too, makes statements that sound like paraphrases of Wilde: "Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand." And: "Nature and art, being two different things, cannot be the same thing. Through art we express our conception of what nature is not." But he also warns against overambitiousness, the "attempt to paint the invisible and, therefore, the unpaintable."

Art is not a representation of external things, but of the artist's ideas about them. Both Velasquez and Rubens, he notes, painted portraits of Philip IV, but they seem to be two different people.

|

| Diego Velasquez, Philip IV at Fraga, 1644 |

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Philip IV, 1628-29 |

Moreover, art exists independently of history: "there is no past or future in art.... The art of the Greeks, of the Egyptians, of the great painters who lived in other times, is not an art of the past; perhaps it is more alive today than it ever was." (The point could be extended, of course, to literature, to Homer, Virgil, Dante, Chaucer, and Shakespeare.) Nor does an artist, he claims, "evolve": "The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or steps toward an unknown ideal of painting." On the other hand, there "are periods in which there are better artists than in others." (The difficulty here, is that Picasso supplies no solid criteria by which we can judge this.)

And so he rejects the idea that a movement such as Cubism should be regarded as "a seed or a foetus," a stage in the development toward something else. Cubism is "an art dealing primarily with forms, and when a form is realized, it is there to live its own life." Critics who approached Cubism through analogies to "Mathematics, trigonometry, chemistry, psychoanalysis, music, and whatnot" have missed the point. Their comments are "pure literature, not to say nonsense, ... blinding people with theories." And finally he disarms all criticism: "But of what use is it to say what we do when everybody can see it if he wants to?

André Malraux: Art as the Modern Absolute

|

| André Malraux, 1935 |

In this selection from The Voices of Silence (1951), Malraux observes that "the art museum is by way of becoming a shrine" to "a vague deity known as Art." The trend started with the Romantics, who elevated the artist to a kind of priest, and as a consequence changed the artist's concept of his role: "Such men as Velazquez and Leonardo who painted only when commissioned were very different from Cézanne for whom painting was a vocation." And so artists began to claim for themselves a special aim: "to dominate appearances and build anew the world that had vanished from Europe, a world that had known and venerated supreme values" -- i.e., those supposedly proclaimed by God. And so "modern art ... does not sponsor any makeshift absolute" such as those proclaimed by religion "but, at least in the artist's eyes, has stepped into its -- the absolute's -- place. It is not a religion, but a faith. Not a sacrament, but the negation of a tainted world."

Even when the artist is a believer, his art stands apart from his belief: "If Cézanne, the good Catholic, had painted Crucifixions, they would have been Cézannesque, and that is doubtless whey he painted none."

Sacred art and religious art can exist only in a community, a social group swayed by the same belief, and if that group dies out or is dispersed, these arts are forced to undergo a metamorphosis. The only 'community' available to the artist consists of those who more or less are of his own kind.Art in the past took its role and purpose from religion: "Michelangelo, Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt linked men up with the universe; as did even Goya, flinging them his gifts of darkness." With the decline of the universal Christian belief that animated the work of these artists, that gave them patrons and subject matter, the nature and purpose of art was forced to change. "As for the art of today -- does it not tend to bring to men only that scission of the consciousness, whence it took its rise?"

Our culture is now founded on the "spirit of enquiry," on what Malraux sees as "the alarming power" of science. "Our art, too, is becoming an uneasy questioning of the scheme of things." It is the uneasiness that Malraux feels most intensely: "The great Christian art did not die because all possible forms had been used up; it died because faith was being transformed into piety." That is, from an intensely internalized view of one's role in the universe into an external show, a pretense of belief lacking an an essential core. But the "spirit of questioning" that now prevails is "usually anxious and perplexed." In this respect, modern art departs in character from the art of previous ages: "Despite the insatiable questioning basic to Greek thought, the impression Greek art made on the world for many centuries was one of a triumphant affirmation."

The replacement of religion with science has produced "a culture that is not categorical but explorative."

It is quite possible that the successor of the art we call 'modern'will be still more individualist; and it is not impossible that it will assume, to begin with, the form of a resuscitation before developing into a new art, vaster in scope and deeper, born of this resuscitation.Malraux's "possible" future hasn't come to pass yet. Postmodernism is certainly neither vast in scope nor deep.

No comments:

Post a Comment