Realism: Melioristic Realism (F.M. Dostoevsky, George Sand and Gustave Flaubert, H.G. Wells and Henry James)

Realism: Melioristic Realism (F.M. Dostoevsky, George Sand and Gustave Flaubert, H.G. Wells and Henry James)_____

F.M. Dostoevsky: Prophetic Realism

In his letters, Dostoevsky explained that his novel The Idiot was an attempt to represent "a truly perfect and noble man," a task he didn't underestimate: "All writers ... who have sought to represent Absolute Beauty, where unequal to the task, for it is an infinitely difficult one." Like Tolstoy, he bases his ideas about the novel in Christianity, but only insofar as the image of Christ -- the "one figure of absolute beauty" -- gives him an ideal to strive for.

|

| Vasily Perov, Portrait of F.M. Dostoevsky, 1872 |

Dostoevsky's choice of the noblest figures in Christian literature are comic ones: Don Quixote and the members of Dickens's Pickwick club. "The reader feels sympathy and compassion with the Beautiful, derided and unconscious of its own worth. The secret of humour consists precisely in this art of wakening the reader's sympathy."

Dostoevsky's realism was of a different order from Zola's:

I have my own idea about art, and it is this: What most people regard as fantastic and lacking in universality, I hold to be the inmost essence of truth. Arid observation of everyday trivialities I have long ceased to regard as realism -- it is quite the reverse. In any newspaper one takes up, one comes across reports of wholly authentic facts, which nevertheless strike one as extraordinary. Our writers regard them as fantastic, and take no account of them; and yet they are the truth, for they are facts.He proposed to concentrate on the spiritual development in Russia, even though "all the realists would shriek that it was pure fantasy! ... It is the one true, deep realism; theirs is altogether too superficial."

George Sand and Gustave Flaubert: The Counter-Religions of Humanity and Art

|

| George Sand in 1864 |

She urges him to remember that "there is something above art: namely, wisdom, of which art at its apogee is only the expression." She insists on optimism: "to perceive the continual gravitation of all tangible and intangible things towards the necessity of the decent, the good, the true, the beautiful." She admits that "the general aspect is for the moment poor and ugly," but refuses to let go of her expectations for improvement. And she wants him to recognize that he is "about to enter gradually upon the happiest and most favorable time of life: old age. It is then that art reveals itself in its sweetness; as long as one is young, it manifests itself with anguish."

She advises him to make the aim of his books clearer:

L'Éducation sentimentale has been a misunderstood book ... because people did not understand that you wanted precisely to depict a deplorable state of society that encourages these bad instincts and ruins noble efforts; when people do not understand us it is always our fault. What the reader wants, first of all, is to penetrate into our thought, and that is what you deny him, arrogantly.... You say that it ought to be like that, and that M. Flaubert will violate the rules of good taste if he shows his thought and the aim of his literary enterprise.She expresses disbelief in his claim that he "writes for twenty intelligent people and does not care a fig for the rest. It is not true, since the lack of success irritates you and troubles you." She asserts a more sensible version of Tolstoy's view of art: "Whatever you do, your tale is a conversation between you and the reader." By hiding himself from the reader, by insisting on the autonomy of the work, he misses this essential connection. "Keep your cult for form; but pay more attention to the substance. Do not take true virtue for a commonplace in literature. Give it its representative, make honest and strong men pass among the fools and the imbeciles that you love to ridicule.... in short, abandon the convention of the realist and return to the true reality, which is a mingling of the beautiful and the ugly, the dull and the brilliant."

Flaubert calls her advice "affectionate and motherly," which he presumably meant kindly but which sounds condescending. But he rejects her advice with an insistence that he can do no other: "I write according to the dictates of my heart. The rest is beyond my control." And he continues to insist that art should conceal the artist:

I burst with suppressed anger and indignation. But my ideal of Art demands that the artist show none of this, and that he appear in his work no more than God in nature. The man is nothing, the work is everything!Nor does he intend to compromise on his view of human nature: "No monsters, no heroes!" As for style, it remains a primary concern: "Goncourt is very happy when he has picked up in the street some word that he can stick into a book; I am very satisfied when I have written a page without assonances or repetitions.... I try to think well in order to write well. But my aim is to write well -- I have never said it was anything else."

H.G. Wells and Henry James: The Counter-Claims of Content and Form

|

| H.G. Wells, date unknown |

|

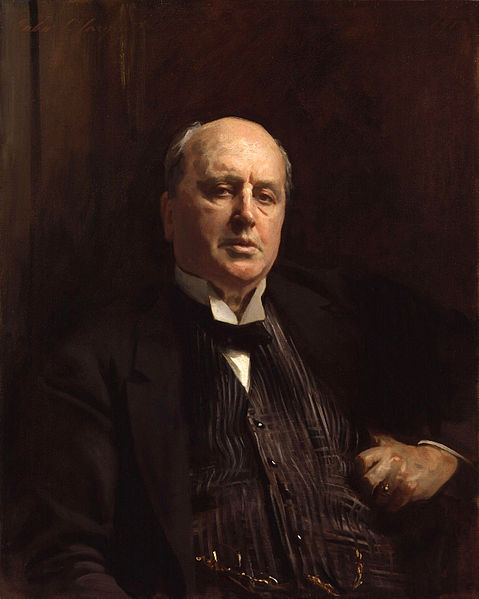

| John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Henry James, 1913 |

He takes Tolstoy "as the great illustrative master-hand on all this ground of disconnexion of method from matter." His "epic genius," however, makes him a bad model: "from no other projector of the human image and the human idea is so much truth to be extracted under an equal leakage of its value." James sees Bennett and Wells as deriving, "by multiplied if diluted transmissions, from the great Russian." Descriptive detail in Bennett's novels gives the reader such a sense of "the solidity of every appearance that it may be said to represent our whole relation to the work and completely to exhaust or reaction upon it."

In Wells's case, he "affects us as taking all knowledge for his province and as inspiring in us to the very highest degree the confidence enjoyed by himself.... The more he knows and knows, or at any rate learns and learns -- the more, in other words, he establishes his saturation -- the greater is our impression of his holding it good enough for us, such as we are, that he shall but turn out his mind and its contents upon us by any free familiar gesture and as from a high window forever open." His books are a kind of brain dump. But James finds him a careless artist, who gives us only the outlines of the experience of his characters.

In Wells's 1934 Experiment in Autobiography, he recalled his acquaintance with James, who "liked me and ... found my work respectable enough to be greatly distressed about it." Where they most disagreed, he says, was that James "had no idea of the possible use of the novel as a help to conduct." James, Wells says, believed in "The Novel ... as an Art Form and ... novelists as artists of a very special and exalted type.... I was disposed to regard a novel as about as much an art form as a market place our a boulevard. It had not even necessarily to get anywhere. You went by it on your various occasions."

James had focused on Wells's novel Marriage in his TLS article, and criticized it because the characters seemed to talk to the reader more than they did to each other. Wells responds,

If the Novel was properly a presentation of real people as real people, in absolutely natural reaction in a story, then my characters were not simply sketchy, they were eked out by wires and pads of non-living matter and they stood condemned.... And the only point upon which I might have argued ... was this, that the Novel was not necessarily, as he assumed, this real through and through and absolutely true treatment of people more living than life. It might be more and less than that and still be a novel.... The important point ... was that the novel of completely consistent characterization arranged beautifully in a story and painted deep and round and solid, no more exhausts the possibilities of the novel, than the art of Velazquez exhausts the possibilities of the painted picture.Wells concludes by questioning whether "The Novel, a great and stately addendum to reality," has ever "been realized -- or can it ever been realized?"

But this autobiographical retort, some twenty years later, was not Wells's first response to James's critique. In 1915, he published a satire called Boon, in which the characters discuss James's fiction.

"He wants a novel to be simply and completely done. He wants it to have a unity, he demands homogeneity.... Why should a book have that? For a picture it's reasonable, because you have to see it all at once. But there's no need to see a book all at once. It's like wanting to have a whole country done in one style and period of architecture."One character suggests that James should "have gone into philosophy and been greater even than his wonderful brother," and argues that "if the novel is to follow life it must be various and discursive. Life is diversity and entertainment, not completeness and satisfaction." James's characters have no "opinions," in them there are "no people with defined political opinions, no people with religious opinions, none with clear partisanships or with lusts or whims, none definitely up to any specifically impersonal thing.... James's denatured people are only the equivalent in fiction of those egg-faced, black-haired ladies, who sit and sit, in the Japanese colour-prints, the unresisting stuff for an arrangement of blacks."

And then comes the often-quoted simile, likening a James novel to "a church lit but without a congregation to distract you, with every light and line focused on the high altar. And on the altar, very reverently placed, intensely there, is a dead kitten, an egg-shell, a bit of string." And the effect of the novel is that of a hippopotamus trying to pick up a pea.

James was not happy with what he called "the bad manners of Boon," and wrote to Wells arguing that "the extension of life ... is the novel's best gift," and asserting, "It is art that makes life, makes interest, makes importance, ... and I know of no substitute for the force and beauty of its process." But it was posterity who gave James the last word, keeping his novels alive while James's, except for the science fiction, are forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment