Book IX

Book IX_____

Milton winds up for the punch by telling us the story is about to turn "Tragic: foul distrust, and breach / Disloyal on the part of Man, revolt, / And disobedience." It's a "Sad task" he has before him, but he insists that the story is "more Heroic" than those of Homer and Virgil or those of "long and tedious havoc" of "fabl'd Knights / In Battles feign'd." His story has a "higher Argument," and he hopes that Urania will help him to "answerable style" and inspire his "unpremeditated Verse." |

| Satan finds his way into Eden, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

Satan is back, having lurked in darkness for a week. He finds his way into Eden via a passage made by the Tigris as it flows out of Paradise, and turns himself into a mist as he "Consider'd every Creature, which of all / Most opportune might serve his Wiles, and found / The Serpent subtlest Beast of all the Field." And he launches into a soliloquy, expressing his admiration of Earth, but also his self-pity because he can't enjoy its delights: "all good to me becomes / Bane." And therefore he has to destroy it, "For only in destroying I find ease / To my relentless thoughts." He even lies to himself: "I in one Night freed / From servitude inglorious well nigh half / Th' Angelic Name." First of all, it took him three days, he lost the battle, his followers are imprisoned, and earlier estimates put his followers as more like a third than half of the angelic host. And now he finds God

Determin'd to advance into our roomAnd to do his dirty work he has to disguise himself as "a Beast, and mixt with bestial slime, / This essence to incarnate and imbrute, / That to the highth of Deity aspir'd." So he goes in search of a serpent and squeezes into its mouth without disturbing its sleep, waiting until morning comes.

A Creature form'd of Earth, and him endow,

Exalted from so base original,

With Heavn'ly spoils, our spoils

|

| Satan in Eden, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

|

| Satan finds a snake to inhabit, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

When Adam and Eve wake up, Eve has a bright idea: division of labor. Working together, she says, they sometimes get distracted: "Looks intervene and smiles, or object new / Casual discourse draw on, which intermits / Our day's work." Adam praises her -- condescendingly -- for coming up with the idea, "for nothing lovelier can be found / In Woman, than to study household good , / And good works in her Husband to promote." But he points out that the work isn't so hard and God doesn't seem to care if they take an occasional break for "this sweet intercourse / Of looks and smiles, for smiles from Reason flow, / To brute deni'd, and are of Love the food, / Love not the lowest end of human life." And he also worries "lest harm / Befell thee sever'd from me." Having heard about the fallen angels, he's aware of the danger.

Eve tells him that she heard that they had such an enemy -- she was standing nearby in "a shady nook" when Raphael told him about it. And she feels hurt that Adam doesn't trust her: "But that thou shouldst my firmness therefore doubt / To God or thee, because we have a foe / May tempt it, I expected not to hear."

Adam backpedals "with healing words," though he's still concerned about how powerful Satan must be: "Subtle he needs must be, who could seduce / Angels." Eve points out,

If this be our condition, thus to dwellGood point, and not unlike the one made in Areopagitica about "fugitive and cloistered virtue." Of course, in that treatise on censorship, Milton was writing about the fallen world. Adam is trying to keep the world from falling, but even so, Eve has put her finger on the problem: a troubled paradise isn't really paradise. Adam is getting a little exasperated with her: He addresses Eve as "O Woman," instead of some of his earlier blandishments, but after lecturing her on reason and free will, he finally gives in: "Go in thy native innocence, rely / On what thou hast of virtue, summon all, / For God towards thee hath done his part, do thine." Milton is not happy:

In narrow circuit strait'n'd by a Foe,

Subtle or violent, we not endu'd

Single with like defense, wherever met,

How are we happy, still in fear of harm?

O much deceiv'd, much failing, hapless Eve,

Of thy presum'd return! event perverse!

Thou never from that hour in Paradise

Found'st either sweet repast, or sound repose;

Such ambush hid among sweet Flow'rs and Shades

Waited with hellish rancor imminent

To intercept thy way, or send thee back

Despoil'd of Innocence, of Faith, of Bliss.

|

| Satan finds his prey, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

For sure enough, Satan discovers her, in one of the last truly lyric passages in the poem, one that echoes the earlier passage about Proserpina:

Beyond his hope, Eve separate he spies,Satan is smitten with both the garden and Eve, like "one who long in populous City pent, / Where Houses thick and Sewers annoy the Air," venturing forth into the fresh air of the countryside. (Hell is a city much like Milton's London.) He's so stunned by her beauty that he "abstracted stood / From his own evil, and for the time remain'd / Stupidly good, of enmity disarm'd, / Of guile, of hate, of envy, of revenge." But if Satan is for a moment "good," it's because he's in a passive state, not because he's capable of being actively good. And it doesn't take him long to come to his evil senses: "Fierce hate he recollects." He gloats that he has found Eve alone, without Adam, "Whose higher intellectual more I shun."

Veil'd in a Cloud of Fragrance, where she stood,

Half spi'd, so thick the Roses bushing round

About her glow'd, oft stooping to support

Each Flow'r of slender stalk, whose head though gay

Carnation, Purple, Azure, or speckt with Gold,

Hung drooping unsustain'd, them she upstahys

Gently with Myrtle band, mindless the while,

Herself, though fairest unsupported Flow'r,

From her best prop so far, and storm so nigh.

And so he sidles up to her, not slithering on his belly because prelapsarian snakes apparently had a way of getting around on a "Circular base of rising folds." And he begins to sweet-talk her as "A Goddess among Gods, ador'd and serv'd / by Angels numberless." She's surprised that he can talk. So he tells her he learned how after eating the fruit of a particular tree. Naturally, she wants to see this tree, and he gleefully leads her there. "So glister'd the dire Snake, and into fraud / Led Eve or credulous Mother, to the Tree / Of prohibition, root of all our woe."

Naturally, she's disappointed: "Serpent, we might have spar'd our coming hither," she tells him. She explains about the prohibition, whereupon he puts on a "show of Zeal and Love / To Man, and indignation at his wrong." He begins to pooh-pooh the prohibition. He tells her he feels the power of this "Sacred, Wise, and Wisdom-giving Plant" and assures her that she won't die if she eats some of it. After all, he didn't. In fact, he's better off because he did: He can talk. "Shall that be shut to Man, which to the Beast / Is open?" Even if God forbade it, it's just "a petty Trespass." God won't really be angry, in fact he'll probably "praise / Rather your dauntless virtue, whom the pain / Of Death denounc't, whatever thing Death be." It's true that threatening Adam and Eve with death and not explaining exactly what it involves is a bit of a problem, but then we've seen the inconsistencies in this whole "knowledge of good and evil" thing before. Satan continues to make the point: What exactly is wrong with "knowledge of Good and Evil"? Wouldn't it be better to know what evil is so you can avoid it?

And finally he appeals to her pride: The prohibition was put in place "to keep ye low and ignorant." If they eat the fruit "ye shall be as Gods, / Knowing both Good and Evil as they know." After all, if a snake can become like a man by eating the fruit, won't a man become like a god?

|

| William Blake, 1808 |

The whole thing sounds reasonable to Eve, and besides, it's almost noon and she's hungry. The fruit is "Fair to the Eye, inviting to the Taste, / Of virtue to make wise." So "she pluck'd, she eat." And the snake beats a retreat as "Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat / Sighing through all her Works gave signs of woe, / That all was lost." Eve gorges on the fruit until she is drunk with it, and begins to worship the tree itself. She even thinks she may have gotten away with it, that "other care perhaps / May have diverted from continual watch / Our great Forbidder, safe with all his Spies / About him." She thinks about keeping it secret from Adam and "keep the odds of Knowledge in my power / Without Copartner." She would become "perhaps, A thing not undesirable, sometime / Superior: for inferior who is free?" (Precisely Satan's argument for rebelling against God.) But then if death is in the bargain, she might die and Adam would marry somebody else. So she decides she has to get him to share the fruit: "So dear I love him, that with him all deaths / I could endure, without him live no life."

|

| Satan slithers away, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

She bows to the tree, which has become her god. The allegory is obvious: She now prefers Knowledge to God. And then she's off to the bower, but Adam, who has woven a garland of flowers for her, meets her halfway, "in her hand / A bough of fairest fruit that downy smil'd, / New gather'd, and ambrosial smell diffus'd." She tells him how much she has missed him, when she really hasn't given him much thought until she realized she might die and he might marry someone else. And then she comes out with it: She's eaten the forbidden fruit, and feels great. And she did it all for him, she lies.

|

| Francis Hayman, 1749 |

"Thus Eve with Count'nance blithe her story told," and Adam is horrified. "From his slack hand the Garland wreath'd for Eve / Down dropp'd, and all the faded Roses shed." He sees her as "Defac't, deflow'r'd, and now to Death devote," and realizes that he can't live without her, that he can't "forgo / Thy sweet Converse and Love so dearly join'd / To live again in these wild Woods forlorn." Even if God created another mate, "Flesh of Flesh, / Bone of my Bone thou art, and from thy State / Mine never shall be parted, bliss or woe."

|

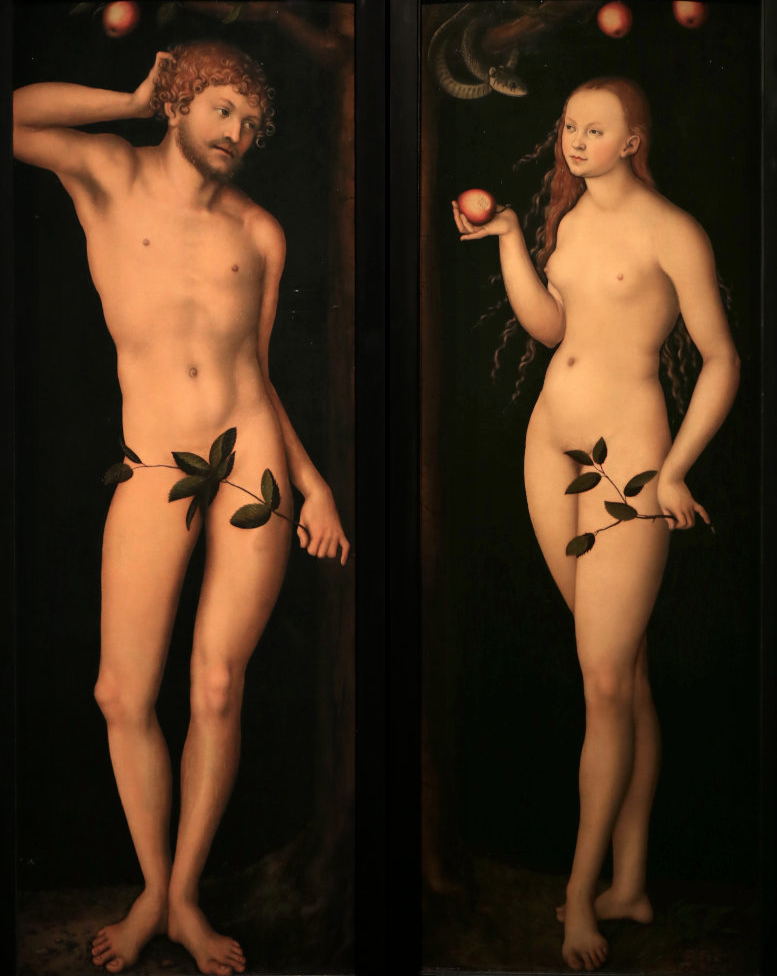

| Lucas Cranach, 1528 |

What's done is done, he decides, and maybe it won't be so bad. Perhaps God won't "in earnest so destroy / Us his prime Creatures, dignifi'd so high, / Set over all his Works, which in our Fall, / For us created, needs with us must fail." So he decides to join her in the fatal act: "Our State cannot be sever'd, we are one, / One Flesh; to lose thee were to lose myself."

Eve rejoices: "O glorious trial of exceeding Love." And she proclaims, "I feel / Far otherwise th' event, not Death, but Life / Augmented, op'n'd Eyes, new Hopes, new Joys." This is as operatic as Tristan und Isolde, and ends with her urging, "On my experience, Adam, freely taste, / And fear of Death deliver to the Winds." So "he scrupl'd not to eat / Against his better knowledge, not deceiv'd, / But fondly overcome with Female charm." This is supposed to be a moment of horror, but long exposure to romantic excess makes it read like an apotheosis.

Adam gorges himself, "Nature gave a second groan," and a storm brews as the "intoxicated" lovers fall to it:

Carnal desire inflaming, hee on EveHe leads her "nothing loath" to a secluded spot where "they thir fill of Love and Love's disport / Took largely."

Began to cast lascivious Eyes, she him

As wantonly repaid; in Lust they burn

|

| After the fall, by Gustave Doré, 1866 |

After "grosser sleep / Bred of unkindly fumes, with conscious dreams / Encumber'd," they wake to humankind's first hangover, "destitute and bare / Of all thir virtue." He berates her for giving "ear / To that false Worm" and bemoans the fact that he can't "behold the face / Henceforth of God or Angel, erst with joy / And rapture so oft beheld." They go to find something "to hide / The Parts of each from other, that seem most / To shame obnoxious, and unseemliest seen." Milton decides that the fig leaves they sewed together must be those of the banyan tree: "Such of late / Columbus found th' American so girt." In the seventeenth-century imagination this denotes that Adam and Eve have become "savages."

They start to argue, and Adam says he shouldn't have listened to her when she wanted to go off by herself: "I know not whence possess'd thee; we had then / Remain'd still happy, not as now, despoil'd / Of all our good, sham'd, naked, miserable." She retorts that he would have been persuaded by the serpent, too, and anyway,

Was I to have never parted from thy side?And so forth, berating each other but neither willing to accept blame. "And of thir vain contest appear'd no end."

As good have grown there still a lifeless Rib.

Being as I am, why didst not thou the Head

Command me absolutely not to go,

Going into such danger as thou said'st?

No comments:

Post a Comment