Chapter 2: The Passage Out; Chapter 3: Boston

Chapter 2: The Passage Out; Chapter 3: Boston_____

There are eighty-six passengers on the Britannia, and they are in for a harrowing voyage. Even at the best, as Dickens notes, there is an "extraordinary compound of strange smells, which is to be found nowhere but on bard ship, and which is such a subtle perfume that it seems to enter at every pore of the skin, and whisper of the hold." You can imagine what a poorly ventilated steamship in 1842 with eighty-six passengers, plus crew, might smell like. Especially when seasickness begins to afflict everyone, as it now does.Everything sloped the wrong way: which in itself was an aggravation scarcely to be borne. I had left the door open, a moment before, in the bosom of a gentle declivity, and, when I turned to shut it, it was on the summit of a lofty eminence.... I am awakened out of my sleep by a dismal shriek from my wife, who demands to know whether there is any danger.... The water-jug is plunging and leaping like a lively dolphin; all the smaller articles are afloat, except my shoes, which are stranded on a carpet-bag, high and dry, like a couple of coal-barges. Suddenly I see them spring into the air, and behold the looking-glass, which is nailed to the wall, sticking fast upon the ceiling. At the same time the door entirely disappears, and a new one is opened in the floor. Then I begin to comprehend that the state-room is standing on its head.A steward informs him, "Rather a heavy sea on." The tumult is followed in the day by "the very remarkable and far from exhilarating sounds raised in their various staterooms by the seventy passengers who were too ill to get up to breakfast." I don't get seasick (except in a porch swing, which makes me terribly nauseated), and remember crossing the English Channel with a lot of people who were. I think it might have been better to be sick and to elicit sympathy for it than to spend one's time dodging effluents. Dickens rather nastily remembers being pleased that his wife was "too ill to talk to" him.

Below decks was bad enough, but when Dickens ventures above, "I could not even make out which was the sea, and which the sky, for the horizon seemed drunk, and was flying wildly about in all directions." And so on, with various Dickensian exaggerations, including his attempt to give his wife and a friend some brandy and water while they are seated on a sofa. The rolling of the ship causes them to slide back and forth. "I dodged them up and down this sofa for at least a quarter of an hour, without reaching them once; and by the time I did catch them, the brandy-and-water was diminished, by constant spilling, to a teaspoonful."

The best assurance he can get from the crew is that the weather is going to improve: "the weather is always going to improve to-morrow, at sea." But finally, after fifteen days of this, they reach Halifax -- or almost, for they get stuck on a mud-bank, and then wind up off course. "Our captain had foreseen from the first that we must be in a place called the Eastern passage; and so we were. It was about the last place in the world in which we had any business or reason to be, but a sudden fog, and some error on the pilot's part, were the cause." But eventually they make it to Halifax, which "would have appeared an Elysium, though it had been a curiosity of ugly dulness. But I carried away with me a most pleasant impression of the town and its inhabitants, and have preserved it to this hour."

|

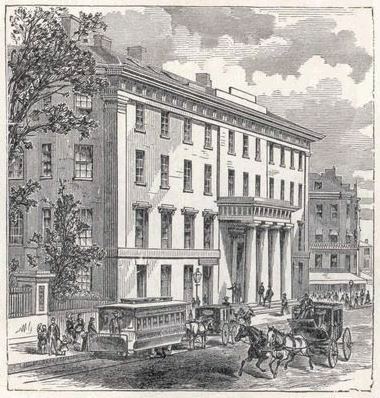

| The Tremont House, Boston, c. 1850-1860 |

Dickens likes Boston. He praises the "courtesy" and the "attention, politeness and good humour" of its officials. He is a bit annoyed on the first morning there, a Sunday, when he is accosted by all manner of people inviting him to their churches. (He had the excuse that his clothes hadn't been unpacked.) He regrets that he didn't have a chance to hear William Ellery Channing preach, especially because of "the bold philanthropy with which he has ever opposed himself to that most hideous blot and foul disgrace -- Slavery." (This is the first reference to the subject in the book.)

The bright, clear air in the city invigorates him, though it seems to him so fresh and new as to be "slight and unsubstantial in appearance.

The suburbs are, if possible, even more unsubstantial-looking than the city. The white wooden houses (so white that it makes one wink to look at them), with their green jalousie blinds, are so sprinkled and dropped about in all directions, without seeming to have any root at all in the ground; and the small churches and chapels are so prim, and bright, and highly varnished; that I almost believed the whole affair could be taken up piecemeal like a child's toy and crammed into a little box. The city is a beautiful one, and cannot fail, I should imagine, to impress all strangers very favourably.

He attributes the "intellectual refinement and superiority of Boston" to the presence of Harvard, or as he calls it, "the University of Cambridge, which is within three or four miles of the city." And he launches into an encomium (which Hitchens thinks somewhat undeserved) of American higher education:

Whatever the defects of American universities may be, they disseminate no prejudices; rear no bigots; dig up the buried ashes of no old superstitions; never interpose between the people and their improvement; exclude no man because of his religious opinions; above all, in their whole course of study and instruction, recognise a world, and a broad one too, lying beyond the college walls.It might be remembered that Dickens was not a university man, and so had a bias against the British universities.

He then turns his attention to "the public institutions and charities of this capital of Massachusetts," which he believes to be "as nearly perfect, as the most considerate wisdom, benevolence, and humanity, can make them." He proclaims his belief in the necessity of public charity: "I cannot but think, with a view to the principle and its tendency to elevate or depress the character of the industrious classes, that a Public Charity is immeasurably better than a Private Foundation, no matter how munificently the latter may be endowed."

He is particularly impressed with the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts Asylum for the Blind. He goes there on a day with "an Italian sky above, and the air so clear and bright on every side, that even my eyes, which are none of the best, could follow the minute lines and scraps of tracery in distant buildings." This is a setup for an encounter with a sightless boy at the school. Dickens is admiring the view when he turns and sees "a blind boy with his sightless face addressed that way, as though he too had some sense within him of the glorious distance: I felt a king of sorrow that the place should be so very light, and a strange wish that for his sake it were darker." It's a strange kind of imaginative sympathy that comes out of a sense of guilt at being gifted with something another person lacks.

It is strange to watch the faces of the blind, and see how free they are from all concealment of what is passing in their thoughts; observing which, a man with eyes may blush to contemplate the mask he wears.

|

| Laura Bridgman, c. 1855 |

He also visits the "State Hospital for the insane" in South Boston, which similarly impresses him as "admirably conducted on those enlightened principles of conciliation and kindness, which twenty years ago would have been worse than hysterical." He's impressed with the way a physician at the institution humors an eccentrically dressed patient in her delusions: "This lady is the hostess of this mansion, Sir," he tells Dickens. "It is obvious that one great feature of this system, is the inculcation and encouragement, even among such unhappy persons, of a decent self-respect." He gets the same impression at the "House of Industry," a home for the elderly poor, and in the adjacent facility for orphaned children of the poor, whose furniture, he notes, is miniaturized versions of adult furniture. This allows him to get in a dig at the English keepers of poorhouses and orphanages: "I can imagine the glee of our Poor Law Commissioners at the notion of these seats having arms and backs; but ... I thought even this provision very merciful and kind."

Virtually the only fault he finds in these institutions is one "common to all American interiors: the presence of the eternal, accursed, suffocating, red-hot demon of a stove, whose breath would blight the purest air under Heaven."

He visits the Boylston school for "neglected and indigent boys," designed to prevent juvenile crime, and a reform school for those who have already committed crimes. "They are both under the same roof, but the two classes of boys never come in contact." And then goes to a prison for adults in which "I found it difficult at first to persuade myself that I was really in a jail: a place of ignominious punishment and endurance. And to this hour I very much question whether the humane boast that is is not like one, has its root in the true wisdom or philosophy of the matter." A part of him thinks that that jail should be a deterrent, like the old practice of exposing executed criminals to the general view, but he admits "that in her sweeping reform and bright example to other countries on this head, America has shown great wisdom, great benevolence, and exalted policy.... I merely seek to show that with all its drawbacks, ours has some advantages of its own."

He also goes to court, to witness that "there is no such thing as wig or gown connected with the administration of justice" and that in America there is no distinction between barristers and attorneys. He also observes, "In every Public Institution, the right of the people to attend, and to have an interest in the proceedings, is most fully and distinctly recognised." On the other hand, the legal system is still prey to obfuscators. He listens to a lawyer addressing a jury "for about a quarter of an hour; and, coming out of court at the expiration of that time, without the faintest ray of enlightenment as to the merits of the case, felt as if I were at home again."

As for social matters, "The tone of society in Boston is one of perfect politeness, courtesy, and good breeding. The ladies are unquestionably very beautiful -- in face; but there I am compelled to stop. Their education is much as with us; neither better nor worse." Religion is heavily oriented toward the evangelical, and "The peculiar province of the Pulpit in New England (always excepting the Unitarian Ministry) would appear to be the denouncement of all innocent and rational amusements." He notes that "there has sprung up in Boston a sect of philosophers known as Transcendentalists," but is somewhat as a loss to explain what the philosophy is: "I was given to understand that whatever was unintelligible would be certainly transcendental." He notes that Transcendentalists seem to be followers of "my friend Mr. Carlyle," and of "Mr. Ralph Waldo Emerson. This gentleman has written a volume of Essays, in which, among much that is dreamy and fanciful (if he will pardon me for saying so), there is much more that is true and manly, honest and bold." And noting that Transcendentalists seem to share "a hearty disgust of Cant," he decides "if I were a Bostonian, I think I would be a Transcendentalist."

Finally, he observes, "The usual dinner-hour is two o'clock. A dinner party takes place at five; and at an evening party, they seldom sup later than eleven; so that it goes hard but one gets home, even from a rout, by midnight." And that "at every dinner, [there is] an unusual amount of poultry on the table; and at every supper, at least two mighty bowls of hot stewed oysters, in any one of which a half-grown Duke of Clarence might be smothered easily."

No comments:

Post a Comment